Corrigendum: The Consensus Statement discussed in this article was written by an international expert panel and is not an official consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association, as it was described in a previous version of the article. To avoid confusion, and to distinguish the advice from that contained in the ADA/EASD consensus on type 2 diabetes management that is also discussed, the article has been updated to reflect this.

When healthcare professionals consider the classification of diabetes, we are all aware of type 1 and type 2. However, in real-life clinical practice, the divide may not be so binary, and there are many cases where the diagnosis is less clear. In such cases, it may be easier to think about whether a person is insulin-deficient, insulin-resistant or both, and to tailor investigations and treatments accordingly, in order to improve outcomes for the individual (Prasad and Groop, 2019).

Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA) is a subtype of diabetes which often falls in between types 1 and 2. LADA is essentially a slowly progressing form of autoimmune diabetes which has immunological markers of type 1 diabetes but which does not necessarily require insulin treatment at diagnosis.

Following the recent publication of a useful Consensus Statement by a international expert panel on the management of LADA (Buzzetti et al, 2020), the present review aims to focus on what healthcare professionals need to know about this condition in primary care.

Diagnosing LADA

The prevalence of LADA is estimated to be between 2% and 12% of all people with diabetes (Naik and Palmer, 2003). This is higher than one may have expected and a good reminder that we are all likely to have people with LADA under our care. The prevalence varies considerably depending on ethnicity, with the highest rates in people of Northern European origin.

It is interesting to note that diagnosis of LADA is much less common in primary than secondary care (Buzzetti et al, 2020). This is not surprising as people with more complex diabetes, and often those on insulin, will be in secondary care. However, in practice, and certainly in the author’s experience, it will often be the case that a person is initially diagnosed with type 2 diabetes but that the autoimmunity progresses and, at some stage, the person becomes insulinopenic and develops the autoimmune-mediated, insulin-requiring condition more characteristic of type 1 diabetes. The primary concern is that the person is at risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) when they become insulinopenic, and so it is highly important that healthcare professionals can recognise this condition in primary care (Davis and Davis, 2020).

The current key diagnostic criteria of LADA are as follows:

- Adult age of onset (>30 years).

- Presence of pancreatic islet cell autoantibodies (e.g. anti-GAD antibodies).

- No requirement of insulin for at least 6 months after diagnosis.

These criteria, however, are certainly not finite and there is much heterogeneity between the clinical presentation and course of LADA from person to person (Pozzilli and Pieralice, 2018).

When might we suspect LADA in primary care?

Diagnosing LADA can be very challenging, particularly in the primary care setting, where access to tests such as autoantibodies is likely to be limited. In ACTION LADA, a multicentre European study that evaluated over 6000 people with adult-onset diabetes within 5 years of their diagnosis, there were no significantly different clinical phenotypes between people with LADA and those with type 2 diabetes (Hawa et al, 2013). The only way to be certain is to check for pancreatic autoantibodies in the blood. There are, however, some clues and broad characteristics that may guide primary care professionals as to when to consider LADA.

1. Age 30–50 years

We tend to consider LADA in people over the age of 30 years simply because below this age type 1 diabetes is more likely, and in LADA we are specifically considering diabetes of adult onset. There is no absolute upper age cut-off for LADA, but studies show that generally the condition is more common when diabetes is diagnosed under the age of 50 years (Buzzetti et al, 2020).

In the UK Prospective Diabetes Study, the presence of autoantibodies in people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes was 34% in those aged 25–34 years compared to 7% in those aged 55–65 years (Turner et al, 1997). Therefore, it makes sense to consider LADA particularly in people aged 30–50 years, but of course the heterogeneity of this condition means that it can be seen outside of this range as well.

2. Absence of metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is the combination of central obesity, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension and insulin resistance. People with LADA are more likely to have metabolic syndrome than people with type 1 diabetes, but less likely than those with antibody-negative type 2 diabetes (Hawa et al, 2013).

In clinical practice, a person diagnosed with type 2 diabetes who has a normal BMI with no features of metabolic syndrome is a good clue for the possible presence of autoantibodies and, potentially, a LADA diagnosis. Of course, this is not always true, and some cases may be indistinguishable from type 2 diabetes with metabolic syndrome (Andersen et al, 2010).

3. Presence of other autoimmune conditions

Positive pancreatic autoantibodies are strongly associated with other autoimmune diseases, particularly thyroid disease (Zampetti et al 2012). There is also an association with coeliac disease (Xiang et al, 2019). A personal or family history of other autoimmune disease is another useful clue when considering LADA.

Screening for LADA

In view of the relatively high prevalence seen in studies (up to 12%), it can be argued that there is value in screening all adults with a new diagnosis of diabetes for autoantibodies. Knowing that someone is antibody-positive will alert clinicians to the possibility of a more rapid progression towards insulin and affect our monitoring and treatment choices (Hawa et al, 2013).

In the Consensus Statement, the panel concluded that general screening for autoantibodies should be used in newly diagnosed, non-insulin-requiring diabetes, and that the one-off cost associated with this test would be justified (Buzzetti et al, 2020). They recommended testing for anti-GAD antibodies, which are the most sensitive marker of LADA and most widely used across the world (Hawa et al, 2013).

This is a controversial but fascinating recommendation. NICE (2015) guidance does not recommend routine use of autoantibodies at diagnosis and only advises using this test when type 1 diabetes is suspected but atypical, such as in people with a BMI of ≥25 kg/m2, age ≥50 years, slow evolution of hyperglycaemia or a long prodrome. Buzzetti et al, however, advise its use across all cases of newly diagnosed diabetes where insulin is not required, which would include everyone diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Obviously this is a very large number of people, with associated cost and practical considerations. This is an interesting area for debate and we need more research to assess the effectiveness of such a strategy. In the UK, the current strategy is opportunistic identification of LADA using the clues we have discussed on a case-by-base basis.

Management of LADA

People with a diagnosis of LADA are likely to be under secondary care management. There have been no specific guidelines for the management of LADA until now. The international Consensus Statement discusses the options in detail and emphasises that management needs to be individualised (Buzzetti et al, 2020).

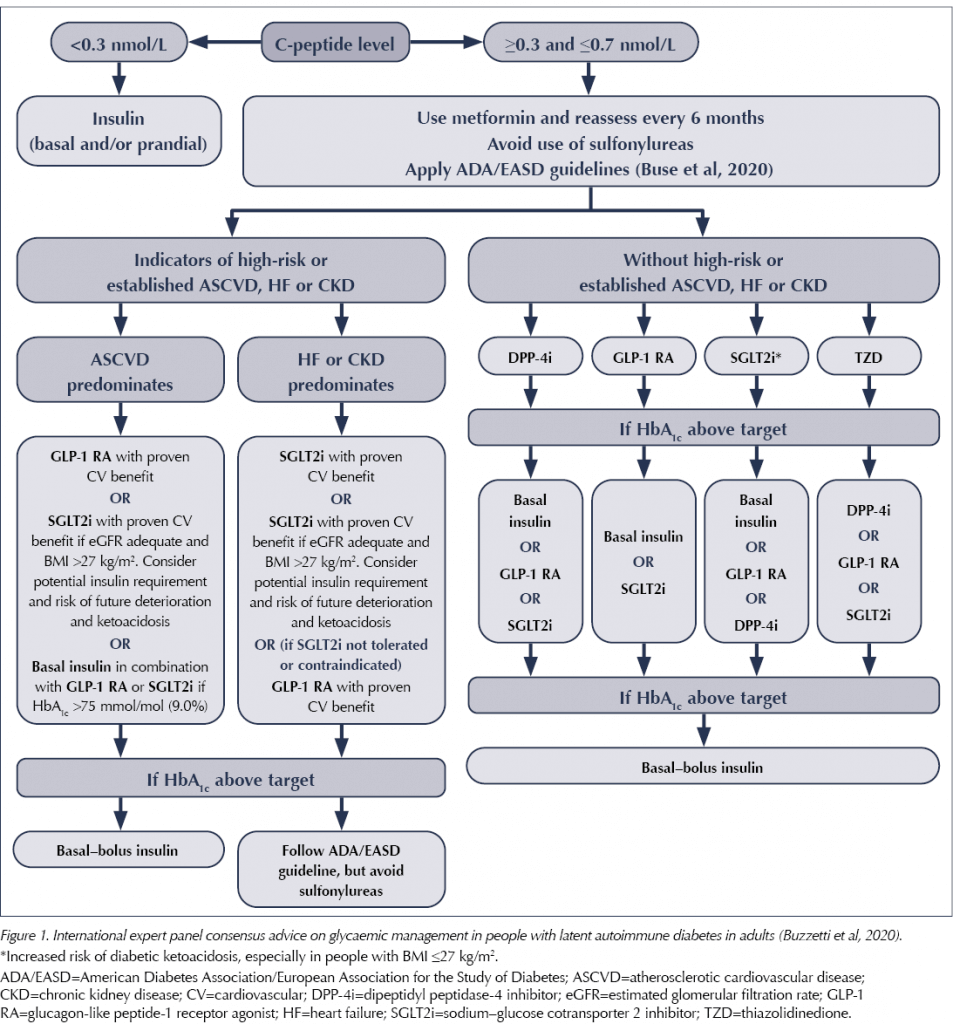

The statement recommends a key role for the use of C-peptide testing in monitoring LADA and deciding on treatment choices. C-peptide is a by-product of the production of insulin by the pancreas. It can be used in LADA to monitor the degree of beta-cell function, and treatment can be matched accordingly using variations of type 2 diabetes treatment. If the C-peptide level is <0.3 nmol/L, insulin is required. At levels above this, treatment can be matched to the individual, with frequent monitoring of C-peptide levels (every 6 months or if glycaemic control worsens).

In terms of treatment choices, if C-peptide levels are maintained, the advised algorithm is similar to the ADA/EASD Consensus Report on managing type 2 diabetes (Buse et al, 2020), except it avoids the use of sulfonylureas altogether, as a more rapid deterioration in beta-cell function due to direct stimulation by this drug class cannot be excluded. This advice is summarised in Figure 1.

Case study

Colin is a 46-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, diagnosed 8 months ago, as well as hypothyroidism. He is currently taking levothyroxine 100 µg and metformin 1 g twice daily. His BMI is 22 kg/m2.

Colin presents feeling generally unwell, with fatigue for several weeks. He also complains of some osmotic-type symptoms over the last week, with increased urination and thirst. Possible slight weight loss of 1–2 kg. No change in bowel habit. He is eating and drinking normally, with no vomiting.

Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, and liver function tests are all normal, but his HbA1c has risen from 61 mmol/mol (7.7%) 3 months ago to 105 mmol/mol (11.8%) now. Colin has continued taking his medications throughout.

What do you think?

Type 2 diabetes diagnosed at age 46 years, no metabolic syndrome, history of autoimmune disease. Sudden deterioration in HbA1c, some osmotic symptoms. We need to exclude DKA.

What do you do?

Examine and assess:

- Random blood glucose: 21 mmol/L.

- Blood ketones: 0.2 mmol/L (normal <0.6 mmol/L).

- All observations normal.

What do you do now?

Having excluded DKA, the case is discussed with the diabetes team urgently. Blood tests are arranged for pancreatic autoantibodies (anti-GAD), that day if possible, and with careful safety-netting in the meantime; Colin will require admission if he develops any symptoms or signs of DKA, such as vomiting, abdominal pain or inability to maintain hydration. Home glucose and ketone monitoring is arranged, and Colin will be seen by the specialist team in urgent clinic that week.

Results

Anti-GAD antibodies were found to be positive, and Colin was diagnosed with LADA. He was commenced on insulin urgently by the specialist diabetes team.

He is now feeling much better, his blood glucose is improving and his HbA1c is coming down.

Conclusions

LADA is a slowly evolving form of autoimmune diabetes. It is important to be aware of this type of diabetes in primary care so that it can be identified early in order to avoid the development of DKA.

It is impossible to diagnose LADA without checking blood autoantibody levels, but there are a number of clues to look for. It is more likely in people between the age of 30 and 50 years, in those with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes but without metabolic syndrome, and in those with other autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease. A typical history often includes a person with type 2 diabetes in whom there is sudden worsening of glycaemic control. There is a debate around the merits of screening for LADA in all people diagnosed with diabetes, but this is not currently advocated in the UK.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025