In recent years, both in the Republic of Ireland and internationally, there has been increased interest in how to deliver integrated care for people with chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes (Health Service Executive, 2008; Kahn and Anderson, 2009). International evidence suggests the nurse specialist has a key role in supporting the integrated management of chronic conditions through delivering nurse-led clinics in primary care (Smith et al, 2004; Ubink-Veltmaat et al, 2005) and providing specialist education and support to professionals in primary care (Johnson and Goyder, 2005; Walsh et al, 2015).

In Ireland, the importance of nurse specialists in chronic condition management and facilitating integrated care has been recognised (Mc Hugh et al, 2013; Begley et al, 2014). As part of the national model of integrated care, the Diabetes Nurse Specialists in Integrated Care (DNSICs) review patients referred to them by the GP or practice nurse (PN), and provide training and support to primary care staff in the set-up and delivery of integrated diabetes care. The DNSICs, when setting up their service with a practice, work with the GP(s) and PN(s) initially to see uncomplicated patients, in order to build experience and confidence at the practice level (Riordan et al, 2018). As structured diabetes care becomes more established, DNSIC reviews more complicated patients. Another purpose of the diabetes integrated care service is to deliver patient education sessions with the PNs, so that they learn from the experience with the aim of becoming independent in delivering structured diabetes care.

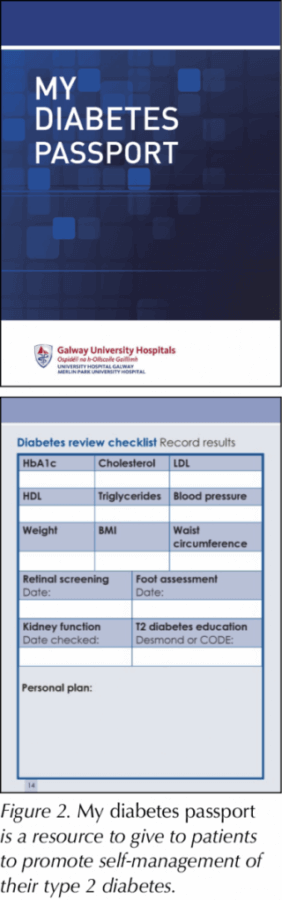

The DNSIC in the current study delivers diabetes care with an empowerment approach that involves reviewing the patients’ agendas first and then building the foundations of learning based on their personal knowledge and motivation to self-manage their diabetes. The DNSIC has developed educational resources to assist with supporting patients’ self-management, including the Diabetes toolkit for practice nurses and My diabetes passport. The Diabetes toolkit for practice nurses (Figure 1) is a practical resource containing checklists and education aids to assist the PN in providing the right information to the person with type 2 diabetes to ensure continuity of care. My diabetes passport (Figure 2) is a resource to give to patients to promote self-management of their condition. Interested readers can email Elaine Newell ([email protected]) for copies of these documents.

The current study aimed to explore GPs’ and PNs’ experiences of working with the DNSIC in primary care as part of the model of integrated care.

Method

A qualitative study was conducted with a descriptive design, using the Framework approach for thematic analysis. The study was conducted in Galway, in the West of Ireland. Ethical approval was granted from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee in University Hospital Galway.

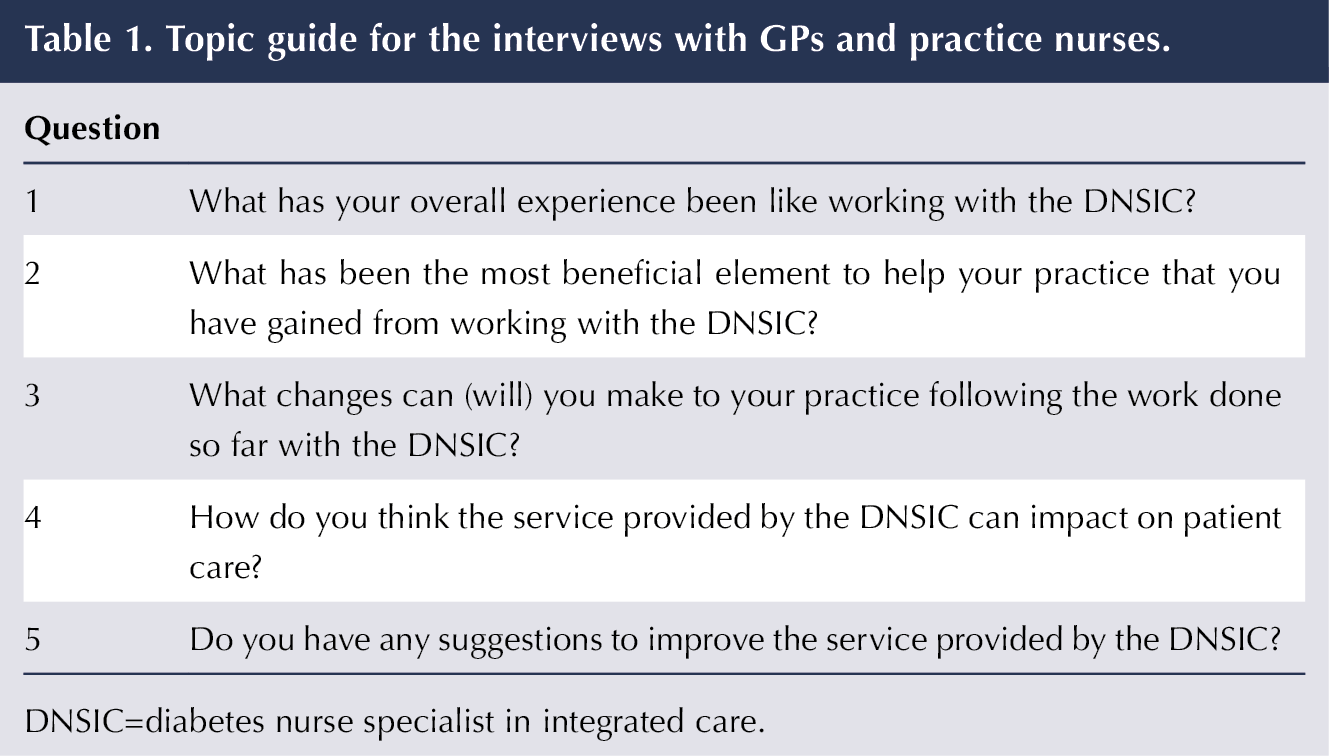

The authors selected a purposive sample of seven GPs and 10 PNs who had experience of working with the DNSIC where regular diabetes clinics were held in the GP practice. Sites were chosen that represented a mix of urban and rural practices and with staff working either single-handedly or within a group. Individual, semistructured, face-to-face interviews took place in the respective practices between September and December 2017, using a topic guide developed by the DNSIC (Table 1). Prior to the interview, an information sheet was given to participants and informed consent was obtained. Confidentiality was maintained. All interviews were conducted by the DNSIC, audiotaped with permission from the participants and transcribed in full. Each interview lasted approximately 10 minutes. Sampling continued until no further information was identified and data saturation was reached (Saunders et al, 2017).

Analysis

Coding was data-driven and analysis was carried out using the Framework method (Pope et al, 2000; Ritchie and Lewis, 2003). The first stage involved the DNSIC becoming familiar with the data by listening and relistening to the audio tapes and making notes about first impressions. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and the transcripts were read a few times to identify ideas and recurring topics. In the second stage, coding was assigned by reviewing the transcripts line by line and labelling relevant phrases, sentences and repeated statements. Making constant comparisons early in the process is important to ensure that integrity is achieved by the researcher constantly “working back and forth” between the data and new codes that are identified (Elliot and Jordan, 2010). Stages three and four involved setting up charts to simplify the coding and allow the key concepts to emerge from the data. Mapping and interpretation involved using the charts to define themes that developed from the data. The interview transcripts were read by two researchers. The themes that developed from the data were discussed and agreement was reached on the themes presented. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) statement was used to inform reporting of the findings.

Results

Seven GPs and 10 PNs were interviewed. The reported overall experience for both GPs and PNs working with the DNSIC was very positive. The following themes were identified.

Setting up structured diabetes care

GPs and PNs felt that the presence of the DNSIC in the practice assisted them with building a better diabetes service that is structured and systematic to ensure continuity of care. These included the set-up of diabetes registers and structured diabetes clinics in all of the practices.

“We are looking at things tighter now as a result of the DNSIC being here and a lot of changes have happened. We have a register; there is structure in place so we know who has had retinal screening, a foot assessment and those who have been lost.” (GP 3)

“The service provided by the DNSIC is excellent. It is very structured and highlighted the importance of providing good diabetes care to patients in a systematic way, covering all areas.” (PN 5)

GPs felt that the integrated care service focused them and came at a good time when they were trying to introduce structured diabetes care within their practice. Similarly, the overall experience for the PNs working with the DNSIC was also very positive, and assisted them in providing structured care:

“Having sat in on the sessions with a DNSIC educating patients, I have learnt how to go through the session in a systematic way so that everything is covered, it has the key structure and is very individualised.” (PN 5)

“I feel I have learnt a massive amount from the DNSIC around how to manage patients with type 2 diabetes and I think we can look after our diabetes patients a little bit better than we did before the DNSIC came to the practice.” (PN 2)

Managing more patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care

Both GPs and PNs commented that the DNSIC service provided them with access to the expertise of a specialist and more knowledge and confidence to manage people with complicated type 2 diabetes in the primary care setting, whereas traditionally these patients would have been referred to the diabetes hospital outpatient clinic:

“For the management of more difficult patients who you would send off a letter for review in the hospital, I now can discuss this patient with the DNSIC and this is hugely beneficial.” (GP 4)

“There would have been patients I would have delayed in treating until I got some advice from the diabetes team and now I am able to treat on site.” (GP 5)

While many of the GPs felt comfortable managing their patients on oral medications, intensifying treatment with insulin therapy was difficult. Traditionally, when patients needed insulin prescribed, GPs sent them to the diabetes outpatient clinic, but now they felt empowered to deliver this service in the practice, with the support of the DNSIC:

“I have learnt more about insulin initiation and am more open to starting it. The mindset has changed because before, when somebody needed insulin prescribed, I would have sent them into the diabetes clinic in the hospital.” (GP 7)

PNs also felt confident with the management of more patients with type 2 diabetes in the GP practice:

“It has taken the fear out of moving patients on to the next step. Before, at a certain point, we would have just sent the patient straight into the diabetes centre but now we have more confidence with the idea of management.” (PN 9)

“I feel I am learning, preparing me to look after my diabetes patients better – the patients the DNSIC does not see all the time.” (PN 1)

Empowerment approach to facilitate self-management of type 2 diabetes

Several PNs commented that, through observing the delivery of diabetes education sessions, they had learnt about using an empowerment approach and the usefulness of techniques such as active listening to assist people with self-management. Some, in turn, had changed their own ways of delivering education as a result of this:

“The patients are going to be more in control of their own diabetes as the DNSIC is handing back the power to them and they feel confident in their diabetes management. I think this style of education is calm and not rushed. It addresses their individual needs and concerns, and is patient-focused.” (PN 10)

“I think the patient is very comfortable with the DNSIC; the language used is non-judgemental; the DNSIC always praises the patients. I think this impacts on how they manage their diabetes; they become more enthusiastic, which empowers them.” (PN 4)

“The DNSIC gives the patient time to answer and doesn’t answer for them. I have noticed what the DNSIC does and I have started not to answer for patients and give them time to answer.” (PN 9)

Resources to assist with patient education

Several of the PNs commented on the usefulness of the resources the DNSIC used in her consultations (the Diabetes toolkit for practice nurses and My diabetes passport):

“The Diabetes toolkit for practice nurses is like the Bible; the visual aids such as HbA1c, cholesterol and the foot assessment tool are very good.” (PN 2)

“They forget a lot when they walk out the door but when they can see it in the patient passport, it helps them retain it and helps keep them motivated.” (PN 1)

The PNs also commented on how they had gained knowledge around different diabetes medications from the DNSIC, and how this knowledge had increased their confidence in managing other people with similar needs:

“I have seen patients come out of the hospital on these new medications, and to learn how to use them correctly really makes a difference. I now feel more confident about these newer medications and insulin, and I have learnt this from doing the sessions with the DNSIC.” (PN 1)

“I enjoy the education session at the end of the diabetes clinic with the DNSIC to review medications and discuss titration of medications with things like impaired renal function. This gives me an idea when I see a similar patient; I know what to do and I become familiar and comfortable with that situation.” (PN 8)

Impact of DNSIC education sessions on patient care

GPs and PNs felt the service provided by the DNSIC positively impacted patient care, with improvements seen in self-management of their condition and their diabetes control:

“Patients become more motivated and interested in their own health when they meet the DNSIC. There has been an impact on the patients’ control when they see the DNSIC, as I see an improvement in a lot of them.” (PN 6)

“I really do think they take on board what the DNSIC says and get a lot from it; that is what they say when they come back for follow-up bloods. I feel that they will change their lifestyle and they know their numbers and want to get blood pressure and cholesterol in target.” (PN 7)

It was also considered beneficial for patients, as they were able to be seen locally by the DNSIC. This was quicker and more efficient, and the patients had greater confidence in the service with the DNSIC in the GP practice:

“When the patient talks about going to the diabetes clinic in the hospital, they are rushed and going from one person to the next. The patients like to come to the GP practice, where it is easier for them and there is continuity when they see the DNSIC.” (PN 2)

The impact on patient care was also reported to have a positive impact on reinforcing the same advice the GPs and PNs were already giving patients. GPs and PNs felt that the DNSIC was a new face reinforcing the same message, and that this made a difference:

“They are listening to me for years and the tune does not change. I think somebody new coming in always makes a difference, and somebody that they know is a specialist in that area definitely makes a difference.” (PN 1)

“I think sometimes you can pigeon-hole the patients as you see them in and out of the clinic the whole time. The DNSIC gives a fresh perspective; it creates motivation, and hearing it from another point of view is huge for the patients.” (PN 9)

Suggestions to improve the diabetes integrated care service

The GPs in this study stated that the diabetes integrated service was valuable and they would not change the clinical delivery, and they felt other GPs should get on board with it. The PNs had similar comments:

“What we have experienced so far is absolutely fantastic. It is structured and individualised, and I cannot think of any way to improve it. I have recommended the DNSIC to other practices who have not yet availed of the service. It has made it so much easier and we are seeing the reviews now.” (PN 5)

It was suggested that having a GP lead or an endocrinologist available in primary care would further facilitate access to a specialist and improve diabetes care. The PNs stated they would like to continue working with the DNSIC to keep up to date, as they were not doing diabetes care regularly and accompanying the DNSIC for the patient education sessions had helped develop their own knowledge and expertise to support their patients.

Discussion

Qualitative research is an important part of exploring the reasoning and responses of stakeholders to a programme (Pawson, 2013). In Ireland, the new DNSIC role was created to support the delivery of a national model of integrated care. The findings from this study are similar to those in other studies. In the Netherlands, the evidence for a shared care model for people with type 2 diabetes with the diabetes nurse as the main care provider was assessed using a quasi-experimental design (Vrijhoef et al, 2002). Results showed that participants’ glycaemic control, diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and triglyceride levels improved, while quality of life and satisfaction scores remained the same. Improvements were also found in knowledge and self-management.

Another study from the Netherlands evaluated structured shared care with DNS support to manage people with type 2 diabetes in general practice, and the results showed that process control (the percentage of patients who had examinations and measurements performed according to guidelines) and outcome control (the percentage with HbA1c, blood pressure and cholesterol levels within target) were higher in the intervention group than in the control group (Ubink-Veltmaat et al, 2005).

Diabetes specialist nurses have been shown to be cost-effective (Courtenay et al, 2007; Art et al, 2012) and to improve clinical outcomes in the community (Health Quality Ontario, 2013; Richardson et al, 2014). In Australia, a retrospective, cross-sectional study assessed diabetes management in a primary care centre where the diabetes nurse provided education (Ginzburg et al, 2018). This intervention involved personal counselling for participants about their condition and how to become empowered to manage their diabetes. The results showed significant improvements in HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol and systolic blood pressure. The findings from the current study in Ireland reflect these results: the PNs felt that patients were empowered to self-manage their diabetes and noticed an improvement in their diabetes control, getting HbA1c and weight to target following education with the DNSIC.

Empowerment of people with diabetes helps them adopt appropriate healthy behaviours and improves self-management practices (Cooper et al, 2008). Research has shown that nurses have a major effect when counselling patients on self-management of their condition and providing decision-making support, with positive effects on both diabetes control (HbA1c and blood glucose) and concordance with disease management (clinic visits, self-monitoring and adherence to treatment; Hainsworth, 2005; Aliha et al, 2013; Watts and Sood, 2016). Within the Galway region in the West of Ireland, the integrated model of diabetes care that includes a diabetes nurse specialist working in the community has had a positive impact on structured diabetes care within primary care. Understanding the impact of the DNSIC working with GPs and PNs can lead to development of standardised diabetes care in primary care.

Another model of integrated care described in the literature is incorporating diabetes virtual clinics. These virtual clinics can take different forms, including remote consultations between the diabetes specialist and the GP and patient together, or professional-to-professional consultations between the diabetes specialist and the GP. Some studies of the specialist-to-generalist type of virtual clinic have found evidence of improved care processes, metabolic control, professional performance and patient satisfaction (Smith et al, 2008; Goderis et al, 2009; Stanaway, 2010). However, with some of these studies, the underpinning theory of the virtual clinics has not been well described to allow adequate assessment of their impact.

Study strengths and limitations

The researcher incorporated strategies to enhance the credibility of this study during its design and implementation. To understand researcher bias, the DNSIC actively engaged in critical self-reflection. Before and during the study, the DNSIC kept a reflective diary containing judgements, impressions and feelings, in order to have open, critical reflection even when the participants provided feedback that may have been negative. Memo-writing can aid researchers’ awareness in realising their potential effects on the data, and can remind them that reflexivity is crucial to eliminate the possibility of prior knowledge distorting their observation of the data (McGhee et al, 2007).

The GPs and PNs were purposely selected to take part in the study because they had worked with the DNSIC, and this working relationship is acknowledged as a possible bias in sampling. To ensure trustworthiness of the data, the researcher was meticulous with record-keeping, ensuring that interpretations of the data were consistent with the participant’s statements. To ensure that the different perspectives from the GPs and PNs were represented, rich and verbatim descriptions of participants’ accounts were included to support the findings. Some participants were asked to review their own interview transcripts and the final themes to validate whether they adequately reflected their statements, and this respondent validation further enhanced the validity of the findings. Two different researchers reviewed the participants’ transcripts and the identified themes independently, and resolved any disparities through discussion to reduce research bias. The DNSIC kept an audit trail to examine the process of collecting, analysing and interpreting data. Reliability can be maximised by keeping an audit trail of the analytic process (Patton, 2002).

Conclusion

As the prevalence of type 2 diabetes continues to grow, new models of integrated care are emerging to support patients. Delivering structured diabetes integrated care can be supported by the presence of nurse specialists in primary care. Understanding the experiences of GPs and PNs working with the DNSIC can assist with understanding how the DNSIC role can be maximised and replicated to support integrated diabetes care in other regions, and can assist in generating knowledge on how best to empower GPs and PNs in the management of people with type 2 diabetes in primary care.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025