In 2019, it was estimated that 463 million people were living with diabetes across the globe, with this figure estimated to grow to 700 million in the next 25 years (International Diabetes Federation, 2019). Diabetes UK (2020) suggests that psychological wellbeing is affected in 40% of people with diabetes. When the two conditions occur at the same time, the outcome of both may become worse (Chwastiak et al, 2014).

Naylor et al (2016) suggest that integrating care will encourage adoption of a holistic approach to ensure all needs of the patient are addressed. Therefore, the intention of this literature review is to explore healthcare professionals’ (HCPs’) perspectives on the integration of diabetes and mental healthcare.

Methodology and search strategy

Bournemouth University’s EBSCO discovery tool, MySearch, was used to explore the following databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, ScienceDirect, socINDEX with Full Text and Complementary Index. Complementary Index was utilised to ensure a thorough search of literature as this database alone displayed over 100 results.

The search terms used to explore the literature can be found in Box 1. An asterisk (*) was used to expand particular search terms, while the Boolean operator “AND” ensured that all variety of search terms were included (Aveyard, 2014). Although the question for review focused on “integration of care”, such search terms were not explicitly used in the final search as, when search terms such as “integrated care”, “multi-disciplinary”, “coordination’’ or “holistic” were initially used, the majority of results were eliminated.

The first line of search terms, which included “healthcare professional”, was amended in order for these search terms to be included in the title of the papers. While this imposes a risk of excluding some data, without limiting this there was an overwhelmingly large number of results, with many that were not relevant to the research question.

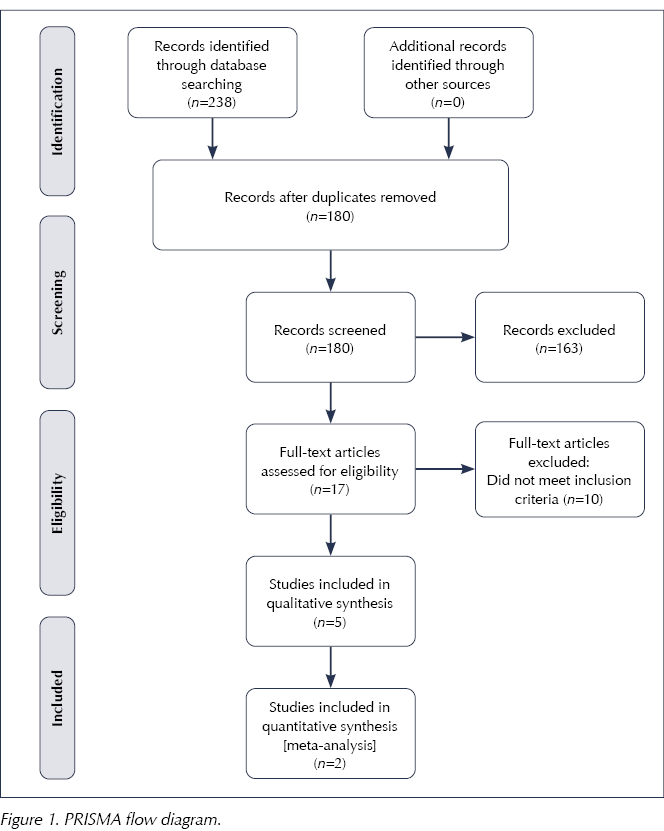

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to search the literature can be found in Table 1. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (Moher et al, 2009) was used to track all phases of the review process (Figure 1).

|

|

There were seven articles that met the criteria, and these were critically appraised for quality using the Critical Appraisal Screening Programme (2018) tool.

Findings

Details of the seven articles and their findings are presented in Appendix 1. The articles originated from the UK, Canada and the Netherlands. The literature contains predominantly qualitative methods, with two randomised controlled trials. Four themes, as follow, emerged from the findings.

Theme 1: Importance of integration

All seven studies found that HCPs recognise that integrated care is important. McBain et al (2018) found that 91% of 237 HCPs felt that the management of mental health and diabetes are equally important. Likewise, Stoop et al (2019) highlighted that addressing psychosocial issues proactively may be beneficial in attempting to reduce patient barriers. The findings of Papachristou Nadal et al (2020) imply optimism from HCPs, as they suggest that bringing together diabetes and psychological care can help to build new pathways of care and management, adding that this has potential to be applied to other long-term health conditions.

Five studies reported that HCPs feel it would be valuable to adapt the style of consultations to a more person-centred and self-management-oriented approach in order to help introduce integrated care. Cimo and Dewa (2019) suggest that establishing client needs and priorities is essential to tailor education and goals.

Theme 2: Confidence and training needs

A theme emerging from five papers involved HCPs’ confidence and ability to manage both conditions. McBain et al (2018) found that only a third of 273 HCPs would feel confident to manage mental illness in a person with diabetes. McBain et al (2016) and Stoop et al (2019) had similar findings. Results show that HCPs who predominantely work with physical illness expressed their worries of working with those with a mental illness and vice versa (McBain et al, 2018).

Due to this lack of confidence, six papers highlighted the requirement for further training and education. Nichols et al (2018) report that HCPs felt they would benefit from further training in depression, anxiety and formal self-management support. In the study by Papachristou Nadal et al (2020), HCPs expressed a lack of training in other disciplines. Similarly, McBain et al (2016) flagged skills that would require development, including communication, confidence, understanding and relationship building. Stoop et al (2019) did not mention this theme in their study, although this may be due to the opposing wish to have the involvement of a psychologist or professional that they could refer patients to instead of being involved in psychological care themselves.

Theme 3: Barriers and resources

This theme, identified within all the studies, includes patient barriers, time barriers and information technology (IT) systems. McBain et al (2016) highlighted the need for longer consultations to be able to address both physical and psychological needs. Graves et al (2016) carried out a trial of a psychological intervention which allowed 30-minute consultations. Nurses referred to the extra time as a luxury as they were able to address more needs. However, there was also an opposing view which suggested that some nurses found it difficult to adapt to this style of practice. Graves et al (2016) and Papachristou Nadal et al (2020) both found issues involving high workload and lack of staff, implying this may be a barrier to implementing integrated care.

An additional need of a combined IT system was raised in three papers, suggesting that this would make the integration of diabetes and psychological care easier to manage. McBain et al (2018) found that 62% of HCPs highlighted this need. Furthermore, four papers conveyed issues relating to patient barriers. These included not wanting to change and non-attendance (Graves et al, 2016), while some HCPs felt that patients would rather focus on the biological aspects of their diabetes rather than psychological needs (Stoop et al, 2019).

Theme 4: Professional boundaries and collaborative working

This theme was identified in most papers, although differing views were presented. Cimo and Dewa (2019) found that some HCPs felt they should have the skills and knowledge to manage both diabetes and mental health issues, while opposing views suggest there should be a multidisciplinary approach in which patients have access to specialist mental health HCPs. Graves et al (2016) reported that nurses felt they were overstepping their role by asking patients about their psychological health.

Two studies raised the suggestion of collaborative working between specialist HCPs; Graves et al (2016) suggested that HCPs require more support from other HCPs for this to be successful, while Papachristou Nadal et al (2020) raised the need for more recognition from a wider body, such as NHS England, to support and innovate this practice. McBain et al (2016) found a majority opinion that primary care professionals should have the overall responsibility of managing diabetes, while mental health professionals should also have further training to help support those with diabetes while predominantly caring for their mental health.

Discussion and limitations

This literature review has provided an insight into the perspectives of HCPs on integrating diabetes and mental healthcare. The findings suggest that HCPs recognise the importance of integrating care; however, many views and suggestions have also been raised regarding implementation in order to make this approach successful.

A randomised controlled trial performed by Bogner et al (2012) involved the use of an intervention group which provided training for HCPs in psychological skills to enable them to provide integrated care. The outcomes displayed that when the two conditions were treated together with a person-centred approach, there was a reduction in blood glucose levels and an improved score of depression from baseline in comparison with a control group. Likewise, de Vries McClintock et al (2016), who also carried out a randomised controlled trial, found similar results and improvements in both parameters. These findings portray the value that integrated care could have on the management of both diabetes and mental health.

A study by Graves et al (2016) involved providing training for nurses to help them develop their psychological skills. A variety of opinions emerged from this training, including the pressure of integrating care adding to already high workloads, as well as mixed views on the time allowance of consultations. It can be concluded from these findings that resistance to change among HCPs may be a limiting factor in implementing integrated care. Farmer and Dyer (2016) recognise that adapting care into an integrative approach will require cultural change, which would be reliant on robust leadership and willingness to experiment.

HCPs from four of the studies highlighted patient barriers as having an effect on the success of integrated care; ideas included lack of engagement, non-attendance and non-willingness to change. Van Dijk-de Vries (2016) carried out a questionnaire to gain feedback from patients regarding their views of integrating their diabetes care with psychosocial care. Overall, 67% of 205 participants felt they would benefit from being asked about their emotional wellbeing, while contrary statements suggest that others would prefer to raise these topics with their GP. These findings suggest that resistance to change in patients may also be a barrier, similar to HCPs. However, HCPs would play a role in providing encouragement to support people to move with new ideas (Naylor et al, 2016). It is possible that HCPs will not know the true outcomes of patient barriers until integrated care is trialled.

The integration of diabetes and mental healthcare is not a linear process. Six papers highlighted the necessity of support from multidisciplinary services and the need of an integrated IT system. The NHS (2019) published a Long Term Plan that aims to address structural issues which involve the merging of the NHS with private sectors and volunteer and community settings, all of which requires a vast amount of planning and time. This emphasises the role that the organisation plays in working with HCPs to implement integrated care.

A significant aspect of this literature review was the recency of the studies. Despite searching from 2009, the oldest articles found were published in 2016, suggesting that this field has only recently begun to be explored. While this is an exceptional motive to perform a literature review, inevitably research was limited. Additionally, the use of inclusion and exclusion criteria may have caused further elimination of research and, consequently, papers may have been missed.

Most of the research used in this review was qualitative. Using qualitative data enables the collection of descriptive responses about individual ideas and experiences, which is essential for the question of review (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015). However, a limiting factor of qualitative research methods are the small scale in which they are usually performed, meaning they may not be representative of the wider population (Anderson, 2017).

Four articles in this review originated from the UK, which could suggest that this arena of research is becoming established here. It is essential to consider the impact of the NHS as a factor in this and its need for sustainability due to increasing demands. Naylor et al (2012) reported that the NHS spends up to £13 billion on treating mental health illness in people with long-term conditions. While integrating care can potentially save the NHS money in the future, the initial hurdle involves building a larger taskforce, which can be difficult due to budget and recruitment issues (Farmer and Dyer, 2016).

Implications for practice and conclusion

This literature review has addressed essential perspectives from frontline HCPs who would be directly involved with delivering integrated care. Four common themes were identified that were valuable in addressing the needs of HCPs to support this transformation. Findings from this literature review and wider reading suggests that there are plans in place to meet the wishes of HCPs as integrated care develops in the future. Farmer and Dyer (2016) composed a strong message within NHS staff with regard to the need for further training. Their aim involves increasing awareness of mental health in front-line staff by providing training to introduce new models of care.

Kozlowska et al (2017) explain that the NHS is now moving towards an interdisciplinary method, rather than a multidisciplinary approach, which aims to have specialised mental HCPs embedded within teams on the front line. Many HCPs in this review raised their concern of lack of knowledge regarding mental health. Education and reassurance of support through the implementation of this new approach may have provided more positive findings.

Research in this field appears limited; therefore, it is essential to continue investigation throughout the implementation process to monitor the true experience, effectiveness and quality of care, and to ensure HCPs are supported in their role, as Graves et al (2016) demonstrated.

NICE (2009) reports that long-term conditions generally can be difficult to manage and can affect the psychological health of an individual. Therefore, a likely implication for future practice may involve expanding integrated care so that other long-term conditions that may impact on mental health, including diabetes, can be managed.

Combined weight loss and sleep apnoea control yields better results than weight loss alone.

4 Feb 2026