Glycaemic events, such as hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia, during admission to hospital are associated with poor outcomes, including increased length of stay, infection rates and mortality (Lake et al, 2018; Dhatariya and Umpierrez, 2023). Successive annual National Diabetes Inpatient Audits have demonstrated the need to improve outcomes and care for those with diabetes during hospital admission (NHS Digital, 2023). This led to the recommendation in the Making Hospitals Safe for People with Diabetes report that all hospitals should have a fully staffed diabetes team, including enough diabetes inpatient specialist nurses (DISNs) to run a seven-day service (Watts and Rayman, 2018).

The diabetes specialist nurse (DSN) role was described as far back as the 1950s. Since then, we have seen the development of subspecialties, including the DISN (Lawler et al 2019). The DISN role is one that, like many specialist nurse roles, requires a diverse set of skills aligning to the four pillars of nursing practice: leadership and management; education; research; and enhanced/advanced clinical practice (Royal College of Nursing, 2024). The DISN supports people with diabetes at various points during their episode of acute care, from pre-admission or admission avoidance through to the weeks following discharge.

A systematic review reported a reduced length of stay and improved clinical care for people with diabetes in hospital after the introduction of a DISN team (Akiboye et al, 2021). Despite this evidence, the National Diabetes Inpatient Audit (NaDIA) in 2019 found that 22% of participating sites had no DISN (NHS Digital, 2021), while the Making Hospitals Safe: Four Years On update showed that, in 2022, nearly half of the sites surveyed still had not fully implemented an inpatient diabetes service (Diabetes UK, 2022).

In 2004, the national DISN UK Group was established, and renewed its purpose and mission statement in 2023 (DISN UK Group, 2024). The group recognises that having an effective workforce, especially in a complex health environment, is not just about the quantity of care, but also equity of care, efficiency, skill mix and knowledge. This present survey was undertaken to better understand the current DISN workforce and their needs in achieving this.

This is not the first survey in the DSN population. Previous surveys by Hicks and James (2020), Lawler et al (2020), Atkins (2016) and Bossman et al (2021) informed the development of this one. Only the Bossman survey, which was also conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic, focuses on the inpatient setting. This survey, therefore, provides new information for a subgroup of DSNs, and will be used to ensure the needs of the workforce are paramount in the DISN UK Group’s work.

Participants and methods

A survey consisting of 21 questions was conducted using Microsoft Forms. The initial questions allowed us to assess the demographics of the respondents by region, nursing band and qualifications. The next questions related to workplace, workload and workforce, to understand the context in which our respondents work. Lastly, we asked questions related to training and development, to understand the training pathway completed, what guidelines support practice and which are still required.

Access to the survey was via a link or QR code, which was circulated to DISN UK Group members via email. National diabetes leads were also asked to disseminate the links to their teams. The QR code was also promoted via social media and as part of planned presentations. This project was considered a service evaluation and, in line with the Health Research Authority decision tool and other similar projects, did not require ethical approval.

Analysis

Descriptive and summary statistics were undertaken using Stata 18. For free-text responses, a qualitative thematic analysis approach was used, initially through coding the data and then by generating themes.

Results

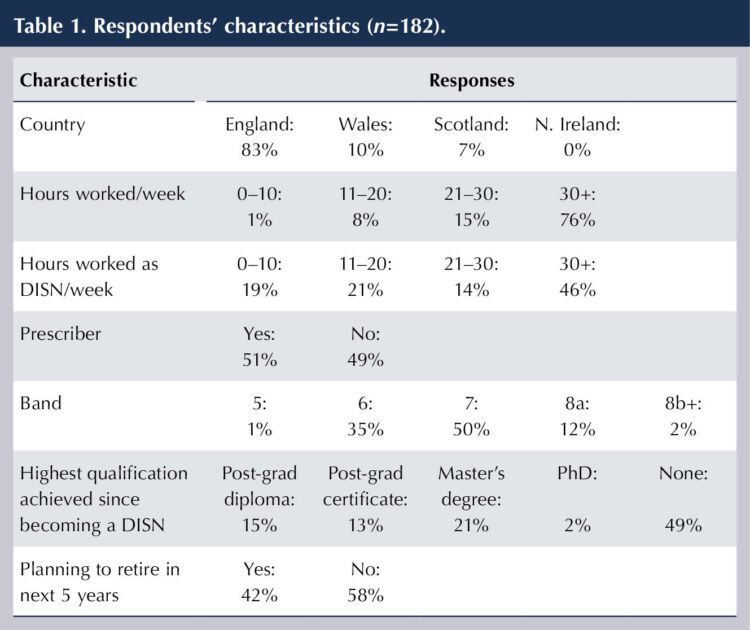

The survey received responses from 182 participants. DISN UK Group has a membership of 375, but we could not guarantee that non-members did not undertake the survey, so a response rate cannot be calculated. Respondents were primarily from England (83%) and typically working at band 7 (50%). Over half reported being prescribers (51%). Nearly half had not attained any significant formal qualification since becoming a DISN, and more than 40% of the respondents stated they plan to retire or leave the profession in the next 5 years. Table 1 outlines the respondents characteristics.

Team and workload

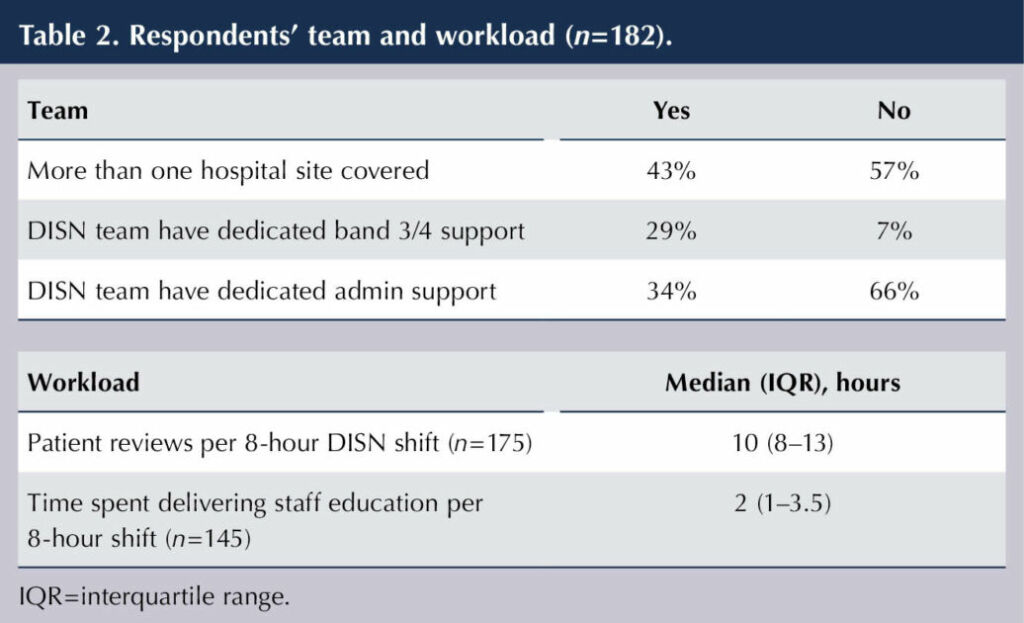

Covering more than one hospital site is common (43%), and most teams do not have any clinical band 3/4 educator or admin support (71% and 66%, respectively). The median (IQR) number of patient reviews during an 8-hour DISN shift was 10 (8–13; min–max, 1–28), which included a median 2 hours of staff education (1–3.5; min–max, 0.4–8.0); see Table 2.

DISN training

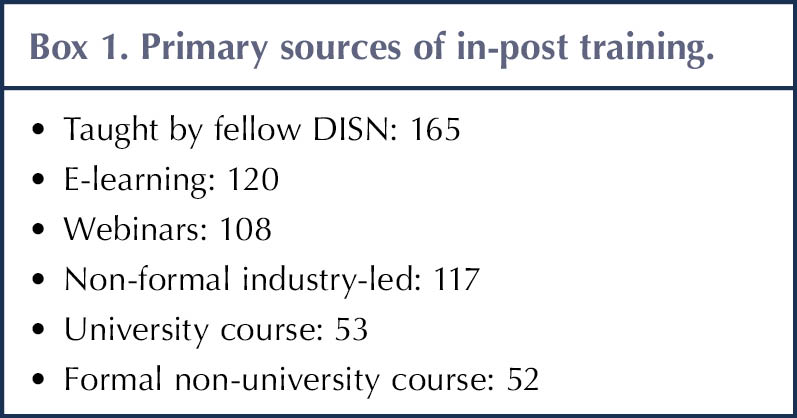

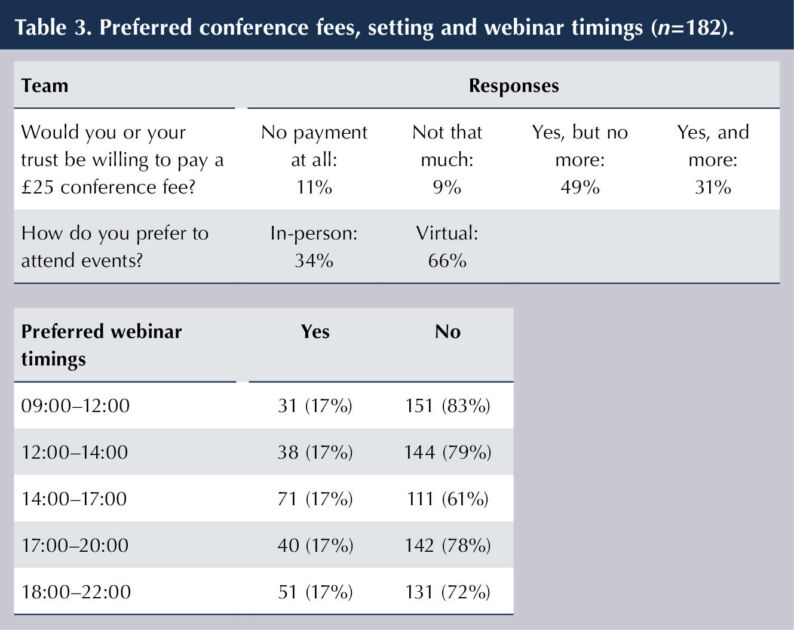

The primary sources of training in the profession are peer-led, e-learning and webinars. The numbers undertaking formal university training or formal non-university training were less than a third of the number taught by peers (Box 1). Of the 182 respondents, 20% reported that they (or their trust) would not be willing to cover a £25 fee for attendance at a conference, although, when asked, most did prefer face-to-face learning opportunities (74%). There was no consensus on a preferred time of day for webinars (Table 3).

Guidelines and support

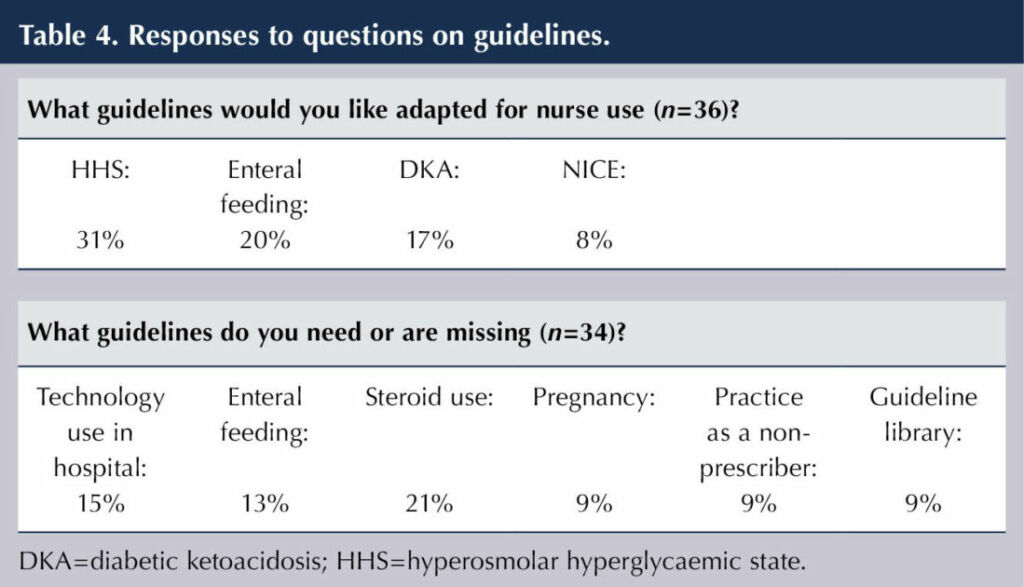

When asked what guidelines relating to inpatient diabetes, of those available, should be adapted specifically for nurse use, 36 were identified. There were four clearly preferred guidelines: hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state (31%), enteral feeding (20%); diabetic ketoacidosis (17%) and NICE guidelines (8%). When asked what guidelines are missing, 34 were identified, with six clearly preferred: technology use in hospital (53%), enteral feeding (15%), steroids (15%), practice as a non-prescriber (9%), pregnancy (9%) and a request for a guideline library (9%); see Table 4.

What do you need from DISN UK Group

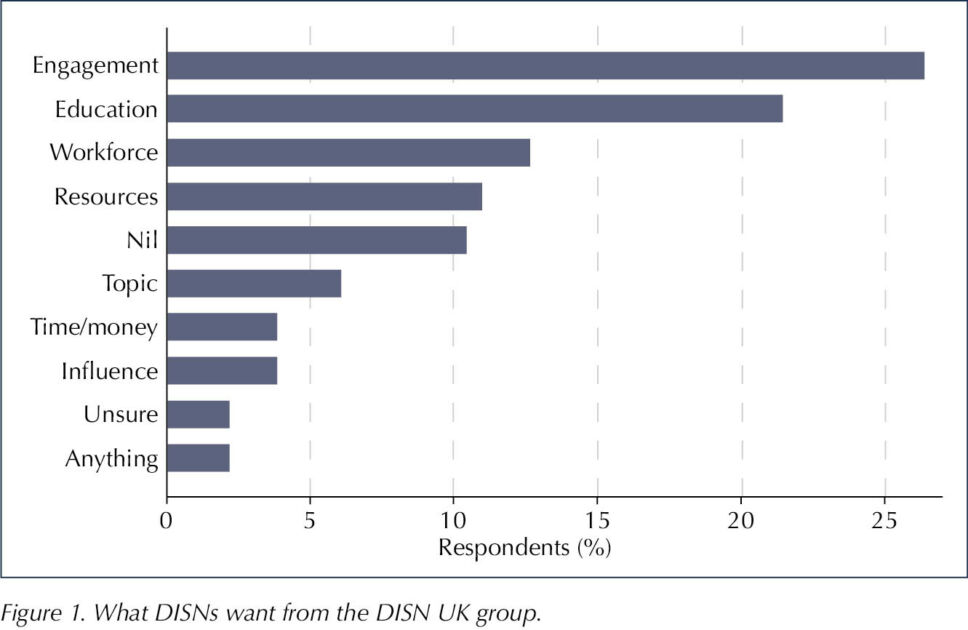

Engagement was the strongest theme amongst responses relating to what the respondents would like from the DISN UK Group (Figure 1). The primary focus was a need for greater peer support and networking opportunities:

“More opportunities for inpatient teams to come together.”

Additionally, there were requests for general updates, including on guidelines, through a variety of channels such as email, webinars and online.

Following closely were the themes of education and workforce. Education included requested learning opportunities, such as case-based discussion, learning from incidents and sharing best practice. Education was thought necessary not only for the DISN population, but also for other healthcare professionals and patients, resources and identified areas of educational need, such as structured education programmes and competencies:

“DISN competencies document that could be rolled out nationally. More formalised training for new DISNs.”

Safe staffing levels was the primary factor relating to workforce issues, with concerns raised about covering a seven-day service, illness and other staff shortages. There was also mention of the role of the non-prescriber amongst the DISN workforce:

“Is it possible to do PGD [patient group directive] for those who are not prescribers?”

“What you are allowed to do as a non-prescriber.”

Equity in service provision, banding, progression opportunities and training was another large contributor to the theme workforce:

“There seems to be a huge discrepancy in banding as a DSN. I am a prescriber and a competent DSN, currently a band 6 and stagnant.”

This links to what is felt to be a lack of recognition for the DISN workforce:

“Hospitals [need] to be accountable to national recommendations of safe staffing for specialist nurses as they are with staff nurses on wards.”

“Unified approach in how to support delivering inpatient diabetes service without being dragged out to do outpatient services (as the needs of inpatients and patients seen in opd [outpatient] are different).”

“Have a dedicated DISN/team.”

The remaining themes focused primarily on requests for more education or guidance on specific topics, such as technology in hospital and provision of resources, grants and influence.

What are your challenges?

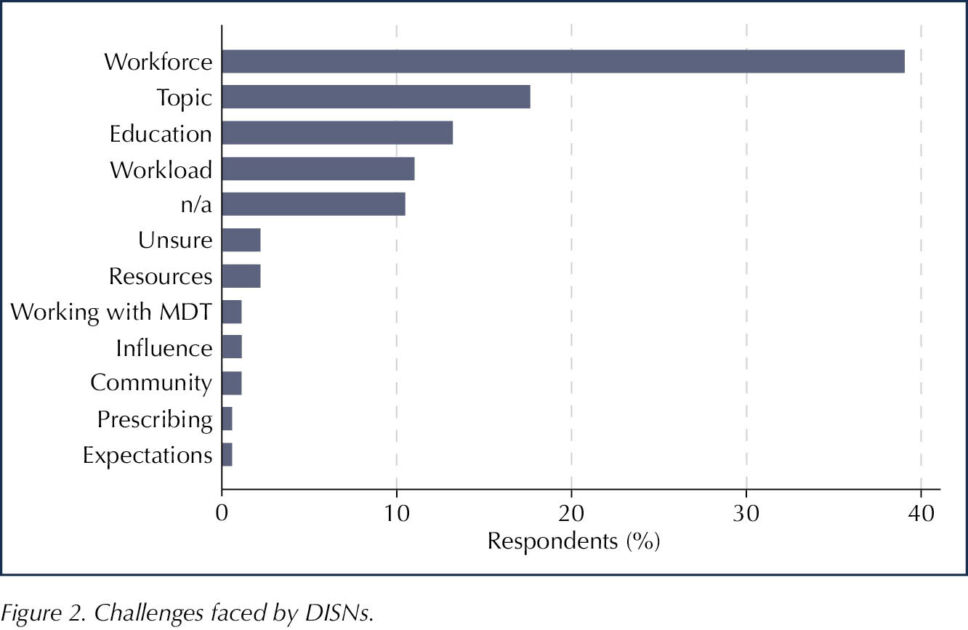

There was a replication of the top themes for what challenges the DISN service are facing when compared to what they identified that they need (Figure 2). Workforce, education and workload were again in the top four themes in terms of frequency. Topic-specific challenges were more frequently mentioned here, with 19 different topics. Of these, technology was the most frequently mentioned.

“Self-management of technologies during inpatient care – supporting/educating frontline staff.”

“Staffing and technology – time for inpatient educators to upskill.”

Safe staffing levels was again the most frequently mentioned workforce issue, followed by the DISN job description and progression pathway, and DISN education, training and support.

“How to develop an inpatient workforce within your organisation and how to promote a future leadership for an inpatient team.”

“Staffing issues. In particular, how do DISNs progress – there is a lot of focus on developing registered nurses into advanced practitioners, but specialist nurses are being forgotten in this process. However, the ANPs/ACPs refer to us for diabetes management.”

Educating the wider healthcare population was the primary education challenge:

“How do you free up ward staff nurse time for education?”

The volume and acuity of the inpatient workload, along with number and quality of inpatient referrals were the primary contributors to the workload theme:

“Not enough staff, immense workload, poor support from consultants, inappropriate referrals.”

“Workload, ever complex patients, lack of medical support. Poor quality referrals.”

“The volume of inpatient work and inpatient referrals is unmanageable.”

“Increased workload, increased clinical inertia in primary/secondary care, increased diabetes distress in the population, impact of cost of living on diabetes care.”

Discussion

The 182 responses suggest that the DISN workforce is keen to engage with the DISN UK Group. Unsurprisingly given the specialised nature of the role, the workforce is primarily band 6 and 7, and, at 51%, the proportion of prescribers is in keeping with those reported by Lawler et al (2020).

The DISN workforce, much like the DSN workforce in previous surveys, continues to face challenges with safe staffing, workload, education and training. Half have not gained any formal post-graduate qualifications since starting in their post. The DISN workforce also raised concerns relating to equity of service delivery, not only within the profession, but also across the specialist and advance nursing workforce.

The development and training for the DISN role is one primarily led by peer-to-peer training. This is not uncommon amongst specialist nurses but, with increasing inequality in banding, recognition and service delivery, there is clearly a need for a structured development programme and competency package that can be used as part of a DISN career pathway. This could be achieved by working with and adapting already nationally recognised competencies from Trend Diabetes and the National Children & Young People’s Diabetes Network. Additionally, whilst the DISN UK Group will prioritise working towards an inpatient-specific training pathway, we will also aim to collate and raise awareness of already available university-accredited modules, including those undertaken as part of the advanced practice training. This would permit careers to follow to recommended enhanced, advanced and consultant pathway, and promote continuity in quality, practice and banding. With nearly half of the respondents reporting that they plan to leave or retire from the profession in the next 5 years, this, along with succession planning, is required urgently.

There is an ongoing need for more national guidance and support in relation to inpatient diabetes guideline development and adaptations for the nursing workforce. An interesting finding was the prevalence of “enteral feeding” as a topic in both the guidance requiring adaptation for nurses and guidance that is missing. This suggests not all DISNs are aware of the JBDS-IP (2024) guidance that is already available.

In the context of the workforce challenges described to achieve safe staffing levels, there is an urgent need for national bodies, such as the DISN UK Group, to support the centralisation of such guidance and of shared resources (like those for service development, business cases, policy, and education) and, importantly, to promote the value, need and recognition of the DISN workforce.

The low number of responses from Wales and Scotland, and a complete omission from Northern Ireland, is a limitation of this survey. It would have also been useful to have insight into the number of trusts represented by the results, and the spread across the regions within England. Despite these limitations, this survey can represent the voice of 182 DISNs. Considering the consistent characteristics and some overlapping findings, it is believed that these results are representative of a significant portion of the DISN workforce. This survey has provided an insight into the DISN workforce and their needs, and will inform the short-, mid- and long-term objectives for the DISN UK Group.

Study finds physical activity particularly beneficial in reducing GDM risk.

20 Jan 2026