The most common foot complication is ulceration, with an estimated annual incidence of 2% and a lifetime incidence between 15% and 25% in people with diabetes (Schaper et al, 2016). Sadly, the 5-year mortality rate of people with newly formed foot ulcers is nearly 50%, a worse prognosis than many cancers (Armstrong et al, 2007; Wukich et al, 2013). Even after healing, the risk for ulcer relapse is very high, with reported rates between 30% and 40% within the first year (Pound et al, 2005, Bus et al, 2013). Additionally, a diabetic foot ulcer precedes 84% of all lower-leg amputations in people with diabetes (Pecoraro et al, 1990).

Preventing foot complications is essential and relies upon integrated care with unhindered clinical referral pathways (Baker, 2006). Foundations of prevention must rely upon identifying those with diabetes who are at risk of foot ulceration. Screening and ulcer risk-stratifying is just the start, and knowing who, where and when to refer is vitally important (Leese et al, 2011). Additionally, being able to give good and, where available, evidence-based foot care advice – and being sure it is understood and implemented – are equally important (Boulton and Malik, 1998; Fletcher, 2006).

This article aims to give a brief overview of common diabetic foot problems and those who need onward referral. Foot conditions such as thickened nails, callus, dry skin and deformities are not a problem on their own but, when present with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD), they can lead to ulceration or amputations (Al-Muzaini and Baker, 2017). Detecting problems early and intervening either by referral or actions can significantly help reduce foot complications.

How do I know if DPN or PAD are present?

Diabetes affects the peripheral nerves in such a way that protective sensations can be dulled or lost, and sweat glands not stimulated, leading to dry skin and muscle denervation, resulting in deformity and altered gait. The latter two are easily determined by clinical observation but the former needs to be tested for. The easiest and most reliable way of doing this is by using a 10 g monofilament to determine intact or lost light touch sensation. This is explained briefly below but comprehensively by Al-Muzaini and Baker (2017).

More difficult to determine is PAD, as this requires both a test and clinical observation. The loss of both pulses in a foot together with an impoverished-looking foot is indicative of possible PAD.

The following is a brief overview of common diabetic foot problems, how to detect them and how to act on them.

NEUROPATHY

Autonomic neuropathy

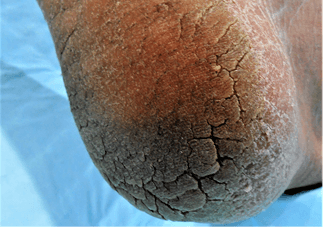

Sympathetic nerves are responsible for vasoconstriction and innervating sweat glands, thereby maintaining good skin moisture. Typically, feet have very dry, warm skin, are slightly oedematous and have strong or “bounding” foot pulses. Very dry skin becomes inelastic, so it is common to find skin fissures (splits), particularly on the borders of the heel (Baker et al, 2005b).

Motor neuropathy

This late complication manifests as a high-arched foot with clawing/retraction of the toes on standing, “hollowing out” between the extensor tendons and altered gait.

Symptomatic neuropathy

This is small nerve fibre damage producing pain or odd feelings such as burning, shooting, stabbing pains or pins and needles. It is not a risk factor for ulceration but can cause depression and is a marker of uncontrolled diabetes. It is generally under-reported, possibly because it may not form part of any formal foot or diabetes review.

Detecting neuropathy

Loss of protective sensation (LOPS)

The most common test used to determine this is simple, cheap, reliable, reproducible and easy to use with little training: the 10 g monofilament test. Inability to feel this is associated with a sevenfold increased risk of ulceration (Adler et al, 1997; Leese et al, 2006).

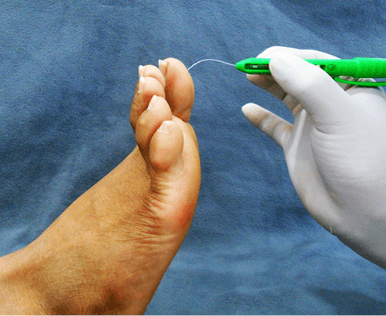

How to use a 10 g monofilament

Apply the monofilament gently to the tip of the first, third and fifth toes until it bends, and then slowly release. With closed eyes, patients should indicate every time they feel the stimulus. Inability to detect one or more site in either foot indicates sensory deficit.

The literature is unclear about where or how many sites should be tested (Baker et al, 2005a). International guidelines suggest the plantar surfaces of the first toe and the first, third and fifth metatarsal heads as appropriate testing sites (Schaper et al, 2016).

If a monofilament is not available you can use a similar technique that uses your finger only: the Ipswich Touch Test (Rayman et al, 2011).

- Improve diabetes control.

- Advice/education.

- Refer for medication if symptoms are lifestyle-limiting or cause insomnia.

|

|

- Oedema.

- Poor technique.

- Abnormal position of arteries.

- Diseased or absent arteries.

- Advice/education.

- Avoid any skin breaks.

- Refer for further assessment.

Shoe rubs are one of the most common causes of foot wounds, particularly when LOPS is present. Any patient with LOPS and foot deformity should be given footwear advice and referred to a podiatrist and possibly an orthotist. Daily self-foot examination for shoe rubs should be strongly advised.

- Advice: Wear correctly fitting shoes, avoid slip-on shoes.

- Daily use of urea-based moisturising cream and see a podiatrist regularly.

- Do not use hard skin-removing products or devices.

- If callus is bloodstained, refer urgently to a podiatrist or diabetic foot centre.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- Xeroderma is best treated by once- or twice-daily use of urea-based moisturisers.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- Simple nail care: nail should be cut following the shape of the toe, not down the sides or straight; file the edges afterwards.

- Advice/education.

- The nail should be thinned; refer to a podiatrist.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- This requires the nail spicule to be removed and possibly the hypergranulation tissue to be removed. This should be referred to a podiatrist.

- If infection is present, antibiotics are required.

- A sterile antiseptic dressing should be applied if there is a wound.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- Apply urea-based moisturisers once or twice daily.

- Steristrips™ can be used to hold the fissure together.

- Follow up for any infection if the fissure has reached the dermis, and apply a sterile antiseptic dressing.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- If the dermis is exposed, apply an antiseptic dressing and review until healed.

- Dry well between the toes, using topical antifungal preparations (powders for inside shoes).

- Follow up regularly until cleared, due to the risk of secondary bacterial infections.

- Reinfections are common, probably due to contaminated hosiery or shoes.

- Silver-impregnated hosiery may be effective.

- Refer nail infections to physicians or podiatrists.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- Identify and remove the cause.

- Use an antiseptic sterile dressing.

- Review frequently until healed.

- If there are no signs of healing in 3–4 days, refer to a diabetic foot clinic.

- Advise patients with LOPS to limit weight-bearing until healed.

- Advice/education.

Action plan

- Ask what shoes are normally worn. If LOPS, deformity or PAD are present, refer to a diabetic foot centre.

- Otherwise, shoes should be long, wide and deep enough to accommodate the foot adequately.

- Advice/education.

Concluding remarks

This is not a comprehensive text on diabetic foot complications but rather a simple overview of the most commonly seen foot conditions. When these are combined with peripheral neuropathy or vascular disease, they can and frequently do lead to serious problems. It is hoped that the information in this article will help non-specialist clinical staff to recognise and know what to do with the conditions mentioned.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025