- 0.98 whole time equivalent (WTE) Band 8a clinical lead and clinical director.

- 2.3 WTE Band 7 nurse.

- 2.4 WTE Band 6 nurse.

- 1.3 WTE dietitian.

The Department’s philosophy includes the following extract, and this provides the context in which this article is based:

“As a team of health care practitioners, we feel that whilst we are employed by the NHS, our first priority is to our patients. To reflect this, we are committed to creating an environment that welcomes users, encourages openness and honesty and develops services that are innovative and responsive to the needs of its users.

Our aim for our patients is that they have the necessary skills and knowledge to manage their health to the best of their ability.”

Diabetes is a long-term condition that requires/demands the person to make multiple daily self-management decisions. These include “healthy” eating, exercise, blood glucose monitoring and, if on insulin, dose adjustments. Effective self-management of diabetes can improve HbA1c levels, reduce the risk of long-term complications, improve quality of life and reduce costs.

Education to support self-management is often delivered in group education programmes; however, people with diabetes often report difficulties applying what they have learnt in daily life, there is often a disconnect between effort and reward, and there may be insufficient support. This may lead them to relax their self-management practices or stop them altogether (Nejhaddadgar et al, 2019).

As a follow-on from group structured education, or for those individuals who have not accessed these opportunities, collaborative and empowering consultations are the key to facilitating individuals to develop skills in problem-solving and decision-making, as well as improving healthcare professional and patient relationships (NHS England, 2019).

In 2001, the department of diabetes and endocrinology at Portsmouth undertook a study looking at patients’ and professionals’ accuracy of recalled treatment decisions in outpatient consultations (Parkin and Skinner, 2003). Both healthcare professionals and patients were interviewed immediately post-consultation and were asked to recall elements of the consultation. In total, 141 consultations were reviewed. Significant disagreement between patients’ and professionals’ perceptions and recollection of the content of consultations was observed. In a further study, Skinner et al (2007) suggested that both patients and professionals had poor recall of the issues discussed (19.6% discrepancy), the decisions made (20.7% discrepancy) and the goals set (44.3% discrepancy).

In response to the results of these studies, the nursing and dietetic team agreed that further personal development of their consultation skills was required. A workshop was arranged and facilitated by a clinical psychologist. During the workshop, the team reviewed a video recording of a team member’s one-to-one consultation with a patient, with prior agreement. Discussions during the workshop highlighted the importance of setting an agenda and the patient having a clear plan of action at the end of the consultation.

The team found the session valuable and wanted to continue with this process in order to develop their consultation skills. It was agreed that each month one team member would video record a one-to-one consultation, with the patient’s consent. The recording would then be shared with the team of around ten people. The reviewee was given control over which points they wished to reflect upon during the review. The process enabled the person to reflect upon their consultation with the support of the team.

Whilst the team as a whole found the process to be a beneficial learning experience, some individuals found sharing their recording with the whole team to be quite daunting, and the team struggled to be constructive and objective in such an open setting.

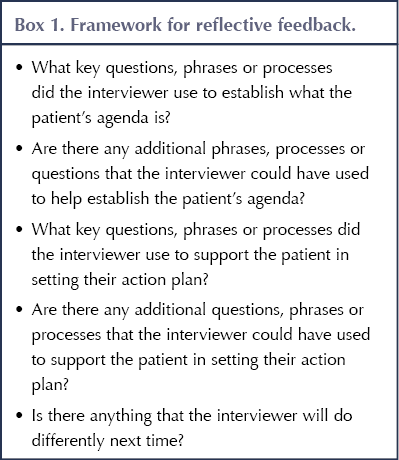

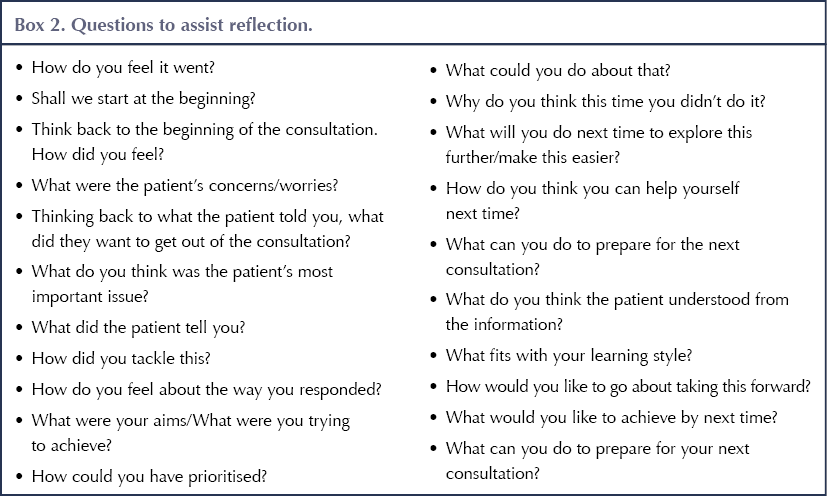

The team continued to reflect and agreed that the key components of the consultation to work on were agreeing the patient’s agenda and supporting them to decide upon their action plan. Various strategies were tried to increase objectivity of the reflections, and in 2010 we reviewed the process in a workshop as part of the department team meeting. An agreement was made on a framework for reflective feedback (Box 1), along with some questions that could be used by the team during the reflective process to support the person reviewing the consultation (Box 2).

|

|

In 2012, two of the diabetes team attended the Knuston consultation skills course in Northampton. This practical course is run for healthcare professionals working with people with diabetes, and explores the philosophy of person-centred collaborative care, its context in diabetes care and how this can be supported with our communication skills. Our nursing and dietetic team gives high priority to attendance on this course, such that 80–100% of staff over the last 10 years have attended the course (variability due to staffing changes).

Early attendees on the course had to share their role-play videos with the whole of the group, including facilitators, which was not popular. Following feedback from attendees, this format has been changed over the years. In 2012, role-plays were reviewed in trios with the reviewee, a reviewer and an observer. Attendees found this a more agreeable process. Using this format, we agreed that each month an hour would be put aside for a team member to share a consultation of around 30 minutes with just two peer reviewers. At the beginning of the session, the reviewee discusses with the reviewers how they wish to structure the review. For example, some agree that only the reviewer can stop the recording to reflect on a point they wish to discuss, while others agree that the reviewers can also do this. A review form is used (Box 2).

Personal reflections

Participant 1: Band 7 DSN

The thought of my patient consultations being recorded was daunting for me. I immediately felt nervous as if I was going to be exposed – but exposed to what? As far as I am aware, I am always friendly and professional, so why the worry? However, I did worry and started to dread the time when I would have to watch myself on video (I am very self-critical as to how I look and sound) and to potentially receive criticisms or sympathetic glances from my colleagues as they tried to rescue me. I was also worried that the consultation would not go to plan – maybe the patient would be difficult, I wouldn’t know how to help them or I might perhaps give inappropriate advice.

The day arrived when the camera was set up in my office. The first patient arrived having given consent for the videoing to commence. I sat in my usual seat making sure the camera was directed just towards me and not the patient. I was surprised to find that, by the end of the consultation, I had forgotten the camera was there. I began to relax into the clinic.

The day came to review the video, and with it renewed nerves. As it was presented to my colleagues I immediately began cursing my low, monotone voice. However, as the consultation went on, I surprised myself with some of the skills I have acquired as a DSN, using open-ended questions, allowing for silences and letting the patient process information, often coming up with answers themselves. I did notice that, with the angle I was sitting, the patient was facing the glass door and one of my colleagues was peering through. I have since moved my chair, so this is no longer off-putting for patients. There were points during the consultation where I maybe missed a point a patient was trying to make or I could have picked up on a thought or feeling. My colleagues were not at all negative; on the contrary, the process allowed us time to explore other ways I could have helped the patient move forward.

On reflection, this has been a positive experience for me. I am now more aware of allowing silences within the consultation and giving patients time to respond, rather than jumping in with my own conclusions. Interestingly, all of the patients I have approached to help with the videoing process have agreed, and hopefully they will benefit in the long term.

Participant 2: Band 7 DSN

Despite researching and reading about video use in consultations many years ago, nothing prepared me for the mixed emotions I felt actually doing it. I was both excited and afraid. I was going to be doing something I had only read about. What would my colleagues think of what I was saying, was it correct, were they going to laugh at me, how would I feel seeing myself on video (something I usually try to avoid at family gatherings)? But I needn’t have worried; the whole experience was enlightening.

The first time I used the video, I recorded my whole clinic and then spent the evening carefully analysing what I considered the “best one” to replay to my colleagues. Conversely, the ones I have gained most from are the random clips that I record last-minute, as these are the ones I don’t have time to think about and are therefore most probably a more accurate picture of how I conduct my consultations. I would by no means describe myself as really good at consultations – I’m not even sure I know what that looks like – but I feed on the discussion we have around my video clips and use it when I can. Feedback is designed to be constructive, to highlight areas for reflection. We rotate the peer review so different opinions come through each time. A structure to questioning is available for those new to peer review or needing a refresher. To anyone or any team considering this approach, I have no hesitation in recommending it as a tool to self-develop.

Participant 3: Band 7 DSN

When taking part in consultation skills and having myself videotaped for others to view, my palms immediately started to sweat and the nerves set in! The thought of others watching me in action, and of course watching myself, was intense: “How critical will this be?”

What I soon learnt was to adopt an open, critical approach. This helped me to relax and feel less conscious of myself. My colleagues were there not to judge me, but to give valuable feedback. After all, this is how patients see us.

Developing consultation skills takes time and practice. Using self-criticism and self-awareness is optimal to improve our relationships between nurse and patient, and refining our skills can only lead to better care for our patients. I now pretend the video camera is always watching, to keep my skills developing.

Participant 4: Dietitian

I find the process of reviewing my consultations very positive. It ensures I take time to reflect on my approach and heightens my awareness of whether I am actually doing what I think I am doing. I am human and, despite the best of intentions, it is not always easy to follow the patient-centred approach and it is easy to slip into old ways. I prefer doing the review as a trio rather than with the whole team; it is less threatening and has removed the feeling that I need to present a perfect consultation.

Participant 5: Band 7 DSN

When I agreed to embark on the project around our consultation skills, I initially felt apprehensive. This was to be a video recording of our one-to-one consultations, with the consent of the patient and reviewed by the nursing team. Although I found the process daunting, I saw it as a positive way to improve my consultation skills, highlighting my strengths and weaknesses.

Although I felt quietly confident that I create the right environment for my patients and have good body language and listening skills, the process enabled me to focus on establishing the patient’s agenda from the start of the consultation, summarising the key points of the consultation and setting a clear plan of action. As a result of this process, I feel that my consultations are more person-centred.

Participant 6: Band 6 DSN

The review process has been really valuable in terms of observing practice, interactions and consultations with patients in the clinic setting. Having taken part in this experience both as a newly qualified member of the team and now having gained more experience as a diabetes nurse specialist, I have taken different approaches to the process. Initially, the process seemed somewhat daunting and I was conscious of being filmed, and as such my behaviour is more than likely to have changed. The latter time I took part in the process seemed more fluid, and I feel as though I would have behaved more naturally, almost as if the camera was not there at all.

Having taken part, I believe I am more conscious of questioning the things that my patients say and delving deeper into their understanding of statements. I am also more conscious of body language and potentially irritating habits, such as clicking the end of my pen.

Discussion

The department of diabetes and endocrinology’s caseload is predominantly people with complex needs, who require ongoing support to manage their diabetes. Diabetes is a demanding long-term condition; many patients find it difficult to maintain the daily self-management routine and struggle with the consequences, such as poor glycaemic control.

Diabetes management is all about performing self-care behaviours; therefore, our consultations require us to work in a behavioural rather than a medical model. The early research in the department carried out by Skinner et al (2007) demonstrated that, as a skilled team, we were failing patients in our approach. Overall, 19.6% of patients did not correctly recall the issues discussed during the consultation, 20.7% did not recall the decisions made and 44.3% recalled different goals set, and these findings indicated that a change in our clinical practice was required.

The decision to video record our consultations for peer review was not taken lightly, and the personal reflections demonstrate the apprehension the team felt. However, all of the participants feel they have benefitted from the process and have improved their consultations. The structure put in place and the evolving process demonstrates the reflective nature and practice of the team.

The revalidation process for the Nursing and Midwifery Council requires us to document five accounts over 3 years of reflective practice. The Health and Care Professions Council requires dietitians to collect evidence of continued professional development, and it randomly audits 2.5% of the profession each year. The process described in this article actively contributes to the participants’ portfolios of evidence. Post-consultation review, the team member completes a form that is used in our portfolios as evidence of reflection both for the reviewee and reviewers. The current format ensures each team member is part of this reflective process three times per year. The team agree this is a valuable ongoing process in the department, which demonstrates the continual striving for the development of our consultation skills.

This process has not been without challenges due to the limited outpatient workload of some team members. The team has embraced this initiative; however, newer team members have reflected that the original whole-team review of the videoed consultations could provide a greater opportunity to learn from peers.

Has it made any difference? Clearly, the process has influenced the professional development of the nursing and dietetic team in the department; however, it is unclear whether it has improved patient outcomes. Ideally, repeating the research of Parkin and Skinner (2003) and Skinner et al (2007) would provide evidence of this; however, the time needed to do this is not feasible, as the workload of the diabetes nursing and dietetic team has increased significantly over the intervening years, and furthermore the original research was carried out with additional staff. Nonetheless, persevering with this process will continue to contribute to the professional development of the nursing and dietetic team, and it is hoped there will be an improvement in the agreement between healthcare professionals’ and patients’ recall of what was actually discussed in the consultation, the decisions made and the goals set. This should contribute significantly to an improvement in outcomes; however, measuring the impact of shared agenda-setting and decision-making is complex. NHS England is currently testing approaches with a view to developing tools/approaches and guidance on this (NHS England, 2019).

Recognising and addressing emotional distress to improve metabolic and transplant outcomes.

15 Jan 2026