Noah, a four-year-old boy, presented to accident and emergency with increased urination, thirst and severe weight loss. Blood tests confirmed a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. He was started on insulin therapy, receiving multiple daily injections of the long-acting insulin Levemir and the fast-acting insulin NovoRapid. Real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was commenced, as recommended by NICE guidelines (NG18; NICE, 2023a).

Assessment

During a first meeting, it is important for the diabetes team to assess the family and identify any additional needs, such as a learning disability. The Department of Health and Social Care (2001) describes learning disability as a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills (impaired intelligence). The Equality Act 2010 states that people with learning disabilities may need additional support and have the legal right to reasonable adjustments when requiring healthcare services (Public Health England, 2020).

According to NICE guidelines (NG93; NICE, 2018), it is crucial to consider how the individual’s learning disability impacts their specific needs and support requirements. This can be assessed through direct interactions with the family, ensuring that other professionals involved are aware and that bespoke education can be provided to meet the family’s needs.

During the initial assessment, Noah’s mother, Lara, disclosed to the diabetes team her diagnosis of DiGeorge syndrome (22q11 deletion). This syndrome affects attention, working memory, visual–spatial memory and mathematical ability (American Health Association, 2023). Being aware of Lara’s cognitive disability meant that reasonable adjustments were made regarding communication and education, enabling a strong connection and rapport to be developed and maintained.

Additionally, the diabetes team used the assessment framework triangle to consider the child’s developmental needs, the parent’s capacity to respond appropriately, and the wider family and environmental factors (London Safeguarding Children Partnership, 2022). This ensured that the team could adapt the education provided, and be aware of any challenges and potential solutions that might arise during the process.

Diabetes education

Throughout the family’s journey, a person-centred care approach was employed to establish a collaborative partnership between the diabetes team and Noah and his mother. The team focused on empowering Lara to manage Noah’s diabetes effectively, tailoring education strategies to meet her unique needs and ensuring she fully understood each aspect of the care process for Noah. This approach promoted confidence and autonomy, enabling Lara to take an active role in Noah’s diabetes management.

For all newly diagnosed individuals, the best practice tariff (Randell, 2012) highlighted the importance of all units providing a structured education programme from diagnosis that is catered to the needs of the child or young person and their family. The family should also receive ongoing updates when attending paediatric diabetes clinic appointments. This is where a checklist is created to ensure that the fundamental topics are delivered. Once competence has been demonstrated, this is signed off. As per ISPAD education guidelines, a completed checklist does not necessarily mean that the family has learned everything they need to know about type 1 diabetes (Olinder et al, 2022).

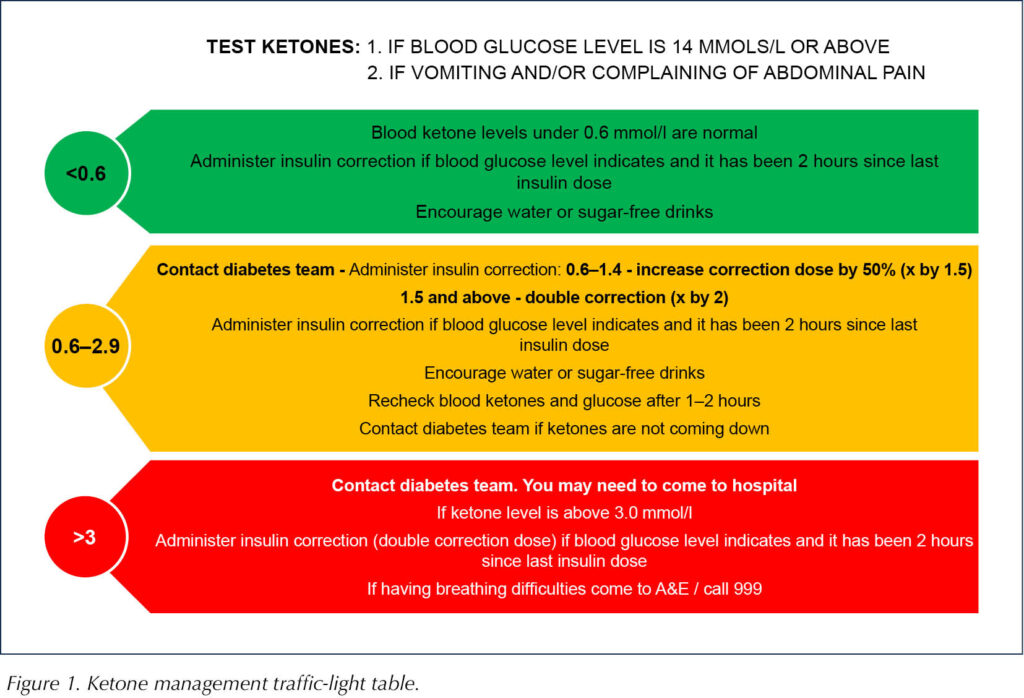

Lara, therefore, received continuous diabetes education post-discharge during clinic appointments and home visits. The education programme included insulin therapy and delivery using multiple daily injections, blood glucose monitoring, nutrition, sick-day rules, and managing hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia. To help Lara safely manage Noah’s ketones at home, Lara was given a traffic-light table on ketone management (Figure 1). She also had access to 24-hour telephone support from the diabetes nurses and the on-call paediatric consultant, through which the team could guide Lara on ketone management.

Owing to Lara’s limited ability to retain information without becoming overwhelmed, the family required a six-week admission on the ward until they were deemed competent and safe to be discharged home. Lara’s understanding was assessed daily using the teach-back method, allowing the team to assess if she could accurately relay the information. The teach-back method enhances patients’ understanding and compliance, leading to better health outcomes across diverse environments, such as hospitals, outpatient settings and emergency departments (Talevski et al, 2020). By using this method, the team identified and focused on the topics Lara found most challenging. The education was tailored to her specific needs and to enhance her understanding and ability to manage Noah’s care.

Education was initially delivered to Lara on multiple daily injections, but her difficulty with maths made this approach unsafe. For example, instead of dialling one unit of fast-acting insulin, she dialled eight.

The diabetes team employed different teaching methods that they believed would be most effective for her. This included using Easy on the i: The Little Guide to Easy Information (Leeds and York Partnership NHSFT, 2024), a concise guide designed to help create easy-to-read materials.

Throughout the education process, simple language was used and jargon was avoided. Pictologics were used, as visual teaching styles with systematic instructions significantly enhance learning outcomes for those with severe disabilities (Cohen and Demchak, 2018). This allowed the team to use images to create a flow chart for all topics, helping Lara visualise the routine for managing Noah’s diabetes. Additionally, diabetes-related objects, such as insulin pens and finger-prick devices, were used in teaching sessions, helping her build confidence.

The diabetes team had concerns regarding Noah’s safety and his mother’s ability to cope at home. Social care was contacted for further support, and it was recommended that an early help referral was completed to enable support at home post-discharge. Lara also expressed concerns about managing Noah’s condition at home and agreed to the support.

Early help provides a coordinated multi-agency approach with a clear plan (Department for Education, 2022). A full assessment was carried out, looking at the family’s needs and strengths. It was agreed that, post-discharge, Lara would receive weekly meetings with her allocated support worker, allowing her to offload any worries and highlight areas requiring further support. Collaborative teamwork with a named nurse provided a direct point of contact. This case highlights the importance of effective communication and collaboration within the multidisciplinary team (MDT) to achieve high standards of practice (Brinks, 2010).

Hybrid closed-loop systems

Hybrid closed-loop (HCL) systems deliver insulin automatically using a mathematical algorithm, adjusting insulin delivery based on readings from a continuous glucose monitor (NICE, 2023b). A discussion with the wider diabetes team assessed if an HCL system would be more appropriate for the family than multiple daily injection (MDI) insulin therapy. ISPAD guidelines (Sherr et al, 2022) recommend pump therapy as the ideal mode of insulin delivery for children with type 1 diabetes under seven years old, as its safety and effectiveness has been demonstrated.

Noah was started on the Omnipod 5, an HCL system, as it was thought it would be more effective and safe for the family. It would ensure Noah’s safety with insulin administration, as insulin and correction doses are calculated by the system. Glucose levels are optimised, with fewer episodes of hypoglycaemia, resulting in lower HbA1c levels compared to MDI (Sulli and Shashaj, 2003). Lara was instantly relieved with how simple the HCL system was compared to MDI, as it removed the need for her to calculate insulin bolus and correction doses.

The MDT assessed Noah’s safety on the HCL system before discharge. This was done through daily bite-size education, observing Lara during pod changes and administering insulin via the controller. The clinical product educator from the HCL company (Insulet) provided further education on navigating the technology, including the SmartBolus Calculator, bolus delivery, and alarms and notifications. The diabetes nurses reinforced this information, ensuring that Lara consistently performed these tasks to assess her competence.

The ward nursing team provided 24-hour support during the inpatient stay, including assistance during mealtimes with carbohydrate counting and insulin bolusing via the HCL pump. The diabetes team supported Lara with insulin settings and making dose adjustments, as needed. Once the team felt she had an optimal understanding of managing Noah’s diabetes with the HCL system, the family was given day and overnight leave to build confidence at home before discharge. Noah’s diabetes management was monitored remotely using the Glooko app. Data was reviewed with Lara and any necessary changes were made to maintain time in range.

Discharge and follow-up

Throughout the family’s admission, the team built a therapeutic relationship and supported Lara in building her confidence to manage Noah’s diabetes autonomously and safely. The team used role modelling and scaffolding learning theory to empower her, providing ongoing guidance in small, repetitive chunks to boost her confidence and develop new skills in managing Noah’s type 1 diabetes. Scaffolding involves providing tailored support to engage the individual when learning a new concept or skill to promote greater understanding and retention in the learner (Tedick and Lyster, 2019).

At the end of the six-week admission, the family was discharged home with a safety-net plan. This included contact details for the diabetes nursing team and on-call paediatric consultant, regular home visits and phone calls for ongoing education. NICE guidelines (NG18; NICE, 2023a) recommend that children and young people with type 1 diabetes attend clinic appointments four times a year. Owing to the family’s circumstances, however, they were seen up to six times a year, to ensure that Noah maintained optimal glucose levels and any issues were identified in a timely, supportive manner.

Conclusion

Families with a learning disability caring for a child with type 1 diabetes require the right level of support and reasonable adjustments, according to individual needs. Effective and collaborative teamwork with the family is essential to ensure readiness for discharge in a smooth and timely manner.

While it is appropriate for HCL therapy to be considered at diagnosis, this decision must be based on the unique needs of the child and family. Research on the use of HCL therapy specifically with parents with learning disabilities is currently limited. Conducting studies for healthcare professionals working with families where learning disabilities are a factor is crucial.

This case study shows the effectiveness of using an HCL system with a family with a learning disability. The team will need to provide ongoing support for managing transition points as Noah grows and develops, as well as empowering his mother, Lara, to manage Noah’s type 1 diabetes confidently.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to acknowledge Birmingham City University’s Children & Young Persons Diabetes Care Module.

Study provides new clues to why this condition is more aggressive in young children.

14 Nov 2025