Diabetic foot ulceration is primarily associated with peripheral arterial disease and peripheral neuropathy, or a combination. However, other factors have a role to play with the risk being increased if the person has a history of previous ulceration (Adler et al, 1999), has callus (Murray et al, 1996), joint deformity (Rith-Najarian et al, 1992), visual/mobility problems and is male (Abbott et al, 2002; Crawford et al, 2007). Diabetic foot screening is recommended in order to identify the level of risk of developing foot ulceration so that effective interventions can be provided (NICE, 2007).

Therapeutic footwear is generally considered to be an important intervention in preventing re-ulceration. This is despite the lack of conclusive evidence for preventing first and subsequent ulcers and the fact that ulcer recurrence rates remain evident in clinical practice (Bus et al, 2008). However, as a component of the whole package of care, including other interventions such as callus debridement (Young et al, 1992; Murray et al, 1996), ulcer management (Cavanagh and Bus, 2010), and patient education (Valk et al, 2005), it has an important role to play if the right shoes are provided to the right patients in the right way.

Assessment of patient foot pressure

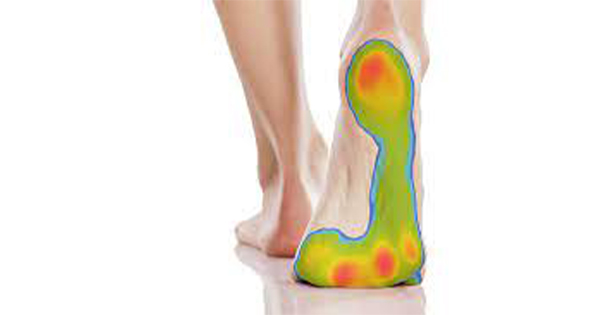

Elevated plantar pressure has been identified as a key causative factor in the development of plantar ulcers (Cavanagh and Bus, 2010). Given that alterations in foot structure, function and joint mobility are known to increase plantar foot pressures, objective and quantitative evaluation tools such as in-shoe plantar pressure analysis could be a helpful addition to the clinical assessment of each patient.

A contemporary review by Patry et al (2013) focused on the role of pressure and shear forces in the pathogenesis of plantar foot ulcers. They recommend that to better assess the at-risk foot and to prevent ulceration, the practitioner could integrate quantitative models of dynamic foot plantar pressures with regular clinical screening examination. However, quantitative methods are not commonplace within clinical practice due to time and financial constraints and issues with usability of the technology.

Undoubtedly, a systematic approach to assessment of the feet in relation to structure, function, and joint mobility is crucial in identifying those at risk. However, the addition of in-shoe pressure assessment would be ideal as part of the prescription process, as recommended by Arts et al (2012). In this ideal situation, the evaluation of foot pressures would need to be carried out prior to footwear provision as a baseline measure, at the point of footwear provision, and at review of the footwear after a period of use.

Evaluating pressures after the provision of therapeutic footwear and optimising its pressure-reducing effects through modification has been shown to relieve pressure by 30.2% (range 18–50% across regions; Bus et al, 2011), and hence can be valuable as part of the review process. The results of an in-shoe pressure assessment could also be used as an educational tool with the patient to encourage engagement with foot orthoses, footwear, and self-monitoring (Williams et al, 2013).

In order to achieve the maximum foot pressure reduction, the correct design features need to be considered as part of the prescription process.

The identification of elevated foot pressures is crucial in the prevention of foot ulceration in those assessed as being at risk. And to achieve this, self-monitoring and clinical review of patients’ feet, foot orthoses and footwear is required.

Therapeutic footwear design

A review of the literature investigating the effectiveness of footwear as a therapeutic intervention found variation in footwear designs (Williams, 2007). However, in clinical practice it is generally agreed that the footwear criteria for therapeutic footwear aimed at people with a risk of foot ulceration is aligned with recommendations for any footwear for this patient group (Nancarrow, 1999).

There are additional foci for specialist therapeutic footwear. Firstly, to reduce forefoot plantar pressures with foot orthoses and appropriately designed outer soles. Secondly, by using soft linings, minimal seams and appropriately place stiffeners to hold the upper material away from the toes, pressures over the dorsum and apex of the toes are reduced. Thirdly, there is a reduction of shear force through secure lace ups (or other fastening) that hold the rear foot in the back of the shoe to achieve a heel that is aligned and supported with heel counter while maintaining protection of the malleoli with padding around the upper of the rear part of the shoe (Williams, 2006).

In relation to the reduction of plantar pressures, a key component is the outer sole material and design. Chapman et al (2013) reported that three design features need to be considered in relation to achieving maximum potential pressure reduction: the apex angle, the apex position and the rocker angle. They suggest that an outsole design with a 95° apex angle, apex position at 60% of shoe length and 20° rocker angle may achieve an optimal balance for plantar pressures of the forefoot. However, they also recommend further studies in order to make definitive recommendations.

There is an inextricable liaison between the foot and the footwear, but the interface between them is crucial and therefore, foot orthoses (insoles) need to be considered as a component of the footwear design.

Burns et al (2009) investigated the efficacy of custom foot orthoses on plantar pressure and foot pain (in those with diabetic peripheral arterial disease) and found that custom foot orthoses significantly reduced plantar pressure compared with a sham, and although there was pain reduction, there was no difference between groups. The authors explain this may well be due to both groups being provided with high quality walking boots and that this was the most important factor in pain reduction. This highlights the importance of footwear design.

Footwear design in relation to pressure reduction is crucial, but this needs to be considered in context of the effects of footwear on balance. In a study by Paton et al (2013), participants said therapeutic footwear was difficult to walk in, heavy, or slippery bottomed. Therefore, attention to these factors is crucial in the choice of footwear to reduce pressures. The authors also made recommendations for achieving enhanced stability with footwear, including a close fit, tight fastening, substantial tread, and a firm, moulded sole/insole.

In relation to insoles/foot orthoses being a component of footwear design, a review by Paton et al (2011) concluded that although there is limited evidence, insoles are considered to be effective in reducing peak plantar pressures and hence the incidence of ulceration. However, they stated that it was not possible to make recommendations for the type and specification of the insole. They stressed the need for a large well-designed randomised clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of different types of insoles/foot orthoses, including economic analysis and patient-based outcome measures.

In addition to plantar pressures, shear is an important factor in the development of pre-ulcerative lesions and ulcers. Lavery et al (2012) evaluated the effectiveness of a shear-reducing insole compared with a standard insole design. The standard insole group was about 3.5 times more likely to develop an ulcer compared with the shear-reducing insole group, suggesting that this may be a useful consideration in the design of foot orthoses and the materials used.

The design and materials used in foot orthoses should aim to reduce both peak pressures and shear forces. Indeed, it may be preferable to patients who are at moderate risk of ulceration to wear appropriate high street shoes with insoles that are designed to reduce foot pressure, while not requiring the extra depth of therapeutic shoes (Miller et al, 2011).

With the current tends to use off-the-shelf foot orthoses, it is useful to consider the benefits of these over customised foot orthoses, such as costs and speed of provision.

However, Fernandez et al (2013) identified that pressure is important, but that it is also the duration over which these pressures may be applied to the foot that is crucial in the prevention of ulceration. Hence, it is vital to know what a person’s typical daily activity level is. Although personalised orthotics and footwear therapy can reduce foot pressures, the duration of foot pressure may well contribute to foot ulceration. Providing individuals with information on foot pressures and the duration of these pressures may help to modify weight-bearing activities sufficiently to reduce the risk of foot ulceration.

Information, education and concordance

The need for objective clinical assessment in footwear prescription is important, but nevertheless patient activity and levels of compliance should be taken into consideration for greater success (Lázaro-Martínez et al, 2014). Indeed, Bus (2012) recommends that offloading should be analysed along with contributing factors to better predict clinical outcome. This includes assessment of patient behavioural factors such as type and intensity of daily physical activity and compliance.

As well as assessing foot pressure, the patient’s level of activity needs to be assessed. This information is crucial in order to provide patients with foot orthoses and footwear of the correct type and design and will help the patient’s understanding and engagement with their footwear.

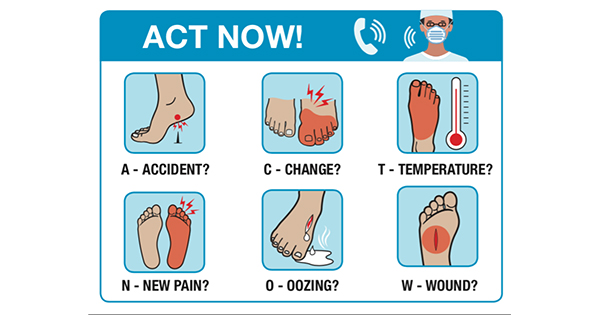

As with any health intervention, compliance is crucial in order to achieve the maximum potential health benefits and this is similarly important in achieving benefits with footwear (Bus et al, 2013). In order to achieve compliance, people need information in order to make an informed decision about their use of the intervention (Figure 1).

The term compliance as positive health behaviour has received bad press in recent years because of the negative labelling ‘non-compliant’ of people who are not engaging and the balance of ‘power’ is perceived to be with the practitioner. However, compliance is what we (as practitioners) want to achieve in order to maximise the potential for prevention of ulceration; this can be achieved through negotiation based on patients being given the appropriate information. Hence, in order to achieve positive clinical and patient-focused outcomes, the focus is now on the consultation where a concordant relationship between the practitioners and patient should be nurtured.

It has been demonstrated (Johnson et al, 2006) that there can be differing views on the role of footwear by the clinician and the patient. This is particularly so for those people who have not experienced an ulcer, whose motivation to wear therapeutic footwear is particularly low.

Therefore, there are issues with differing perspectives in terms of expectations and the reality of preventive behaviour particularly as the choice of footwear designs may not meet the specific needs of patients in relation to the appearance of the footwear.

As well as ascertaining the patients’ needs they should be informed of the benefits of the footwear — especially the short-term benefits, as these will encourage engagement so that longer-term benefits can be achieved.

Consequently, as people with diabetes are focused on the appearance of footwear as a priority (Williams and Nester, 2006) patient perspectives should to be taken into account so that therapeutic footwear designs reflect, as much as possible, those available on the high street. By contrast, Arts et al (2014) found that the most significant determinant for footwear use was the perceived benefit of the footwear. Paton et al (2014a) explored the psychological influences and personal experiences behind the daily footwear selection of people with diabetes and neuropathy. They found that for some, living with the risk of foot ulceration, the decision whether or not to wear therapeutic footwear is driven by the individual’s immediate concerns rather than longer term concerns. Therefore, clinicians should focus on enhancing the patient’s appreciation of the immediate benefits of therapeutic footwear whilst ensuring the social context of footwear and the patients guided choice in relation into footwear style because these can significantly impact on emotional physical wellbeing.

The focus on footwear research and has been on outdoor footwear. However, Waaijman et al (2012) found that compliance with therapeutic footwear was insufficient, particularly in the home where the participants in their study were most active. Despite the potential for footwear to reduce the risk of ulceration, the choice not to wear it indoors is a major threat for ulceration.

Armstrong et al (2001) found that although patients took more steps per hour outside their home, they took more steps per day inside their homes and although 85% of the patients wore their footwear most or all of the time while they were outside their homes, only 15% continued to wear them at home. Patients particularly need information about the use of therapeutic footwear indoors and in relation to their levels of activity.

It is crucial to explain the importance of wearing the therapeutic footwear for periods of high activity, and this includes indoor use. Slippers should not be the footwear of choice for indoor use.

In order to achieve compliance and achieve clinical objectives, we need to ensure that patients wear their footwear sufficiently during periods of high activity. In order to achieve that, practitioners need to understand the existing footwear wearing habits that they have, how patients view the footwear in the context of their lives, and also the compromise that may have to be achieved between footwear as an item of clothing and as an intervention to prevent foot ulceration.

Once the footwear has been supplied and meets the patients’ needs as well as the clinician’s objectives, then monitoring may aid compliance and good outcomes.

Monitoring

The presence of a minor lesion is the strongest predictor for re-ulceration, while the use of therapeutic footwear is a strong protector against ulcer recurrence from unrecognised repetitive trauma (Waaijman et al, 2014). This supports the need for ongoing monitoring of both the feet and the footwear, particularly as the properties of the footwear are likely to change over time, requiring modification and repair.

Insole replacement is triggered only when foot lesions deteriorate and patients are exposed to unnecessary ulcer risk (Paton et al, 2014b). This demonstrates that insoles can be effective in maintaining the reduction in peak pressure for 12 months, regardless of wear frequency. Nevertheless, the frequency of insole replacement is best informed by an objective functional review using an in-shoe pressure measurement system. This monitoring requires attendance at a clinical appointment and also self-monitoring supported with patient information and advice.

Monitoring of the foot, the footwear and the foot orthoses is crucial in order to detect minor lesions early and any changes in the properties of the interventions. This needs to be carried out by both the patient and a skilled clinician with knowledge of ulceration and footwear prescription.

In relation to technology being used for monitoring, Bus et al (2012) assessed the validity and feasibility of a temperature-based adherence monitor to measure footwear use but this has not had wide application in clinical practice. While this can be a useful adjunct to monitor compliance there is still the requirement for assessing the patient’s feet and footwear to ensure that any subtle changes are detected and managed quickly. Indeed, it could be said that if a patient complies more, then there is more need to monitor the footwear in relation to it wearing out and hence reduction of the benefits. Hence, review and monitoring should be based on the patient’s activity and use of the footwear.

An additional reason for monitoring the patient is the potential for the footwear to affect stability in a negative way. It was highlighted by van Deursen (2008) that neuropathy is related to postural instability and an increased risk of falling. Further, he suggests that therapeutic footwear can exacerbate this risk. Although this has received very limited attention in the literature, he notes that patients wearing therapeutic footwear have reduced activity levels, which may be related to instability but may also add to the effect of offloading.

More recently, Paton et al (2013) explored patients’ experiences of instability in therapeutic footwear and found that most did not believe that the footwear contributed to their fall. However, most subjects revealed how footwear influenced their balance and confidence to undertake daily tasks. The authors concluded that people have disease-specific needs and concerns relating to how footwear affects balance. Engaging with patients to address those needs and concerns is likely to improve the feasibility and acceptability of therapeutic footwear to reduce foot ulcer risk and boost balance confidence.

Therefore, it is important for all healthcare professionals involved in the care of people with diabetes to both assess and make recommendations on the footwear needs of patients or refer to those who have such skills and knowledge (Bergin et al, 2013). Patients who require therapeutic footwear need to be monitored by clinicians with experience and skill in this area.

Conclusion

There is less research on the prevention of initial foot ulcers when compared with prevention of secondary ulcers. However, in the absence of research in this specific area, one has to assume that the same strategies for prevention of re-ulceration can be employed in relation to prevention of a first ulcer; this is especially challenging, because engaging patients may be more difficult. There are some recommendations on key aspects of patient involvement (Williams, 2007; Bus et al, 2008), but more research needs to be carried out.

Despite the dearth of evidence, footwear clearly does have an important contribution in the management of foot problems when combined with other foot-related interventions; particularly when provided in a setting that facilitates patient choice and monitoring of footwear in relation to clinician and patient-focused outcomes. Patient understanding about therapeutic footwear and its objectives is a major a factor in influencing the level of engagement necessary to achieve maximum health benefits.

Regular reviews of the footwear and referral back to the service that provided it is recommended to ensure that it retains its original pressure-relieving properties and that it does not result in instability and the risk of falling.