It should be clear to everyone in health care these days that diabetes is set to rise markedly in incidence over the coming decades, bringing with it a host of complications and putting greater burden onto health services worldwide. The future therefore does not look too bright, given the way funding is now and is likely to remain – that is, in scarce supply. But is the future dependent on extra funding to increase services in their current configuration or is something else needed to get better outcomes from that chunk of resources which is currently available?

Multidisciplinary teams: The reality

Shared care has been a popular theme in diabetic foot care – with many people extolling the virtues of multidisciplinary foot teams – and it is enshrined by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE; formerly the National Institute for Clinical Excellence) in clinical guideline 10 (NICE, 2004). However, as a tissue viability nurse and relatively new entrant to the world of the diabetic foot, I would like to know who these teams actually are.

The word ‘team’ suggests that more than one person is present simultaneously when a patient has a consultation. In centres of excellence, I have no doubt that this happens, but outside those walls, the ‘team’ may actually be a single podiatrist who has to make referrals to other professionals. Even with good working relationships, the result is multiple appointments and multiple delays before the patient has seen the necessary people and appropriate care can be devised and put into action.

Of course, during this, a procession of care notes will be made in different records and letters will need to be written to then share the information from these consultations, adding time to the care process and using up available clinical and administrative resources. As is often said, ‘time is money’ – or in this case ‘cost’ – which is as true for the patient as it is for the service, because immobility costs us all dear.

The future of patient-held records

I was fortunate to recently be invited to a Professional Select Committee on the future of diabetic foot ulcers entitled Put your best foot forward (see pages 22–24). In discussing how to improve care, one concept debated was raising awareness of diabetic foot problems through multidisciplinary educational opportunities. This, of course, seems very reasonable, but it is unlikely to bring about tangible change because I strongly suspect that all the relevant professionals are already aware of the clinical issues surrounding diabetic foot care.

Another topic debated was the use of common records and patient-held records, with examples of good practice given. The discussion showed how these initiatives had positive effects for patients by connecting them to their own care and, in doing so, creating that essential partnership between clinician and patient. Correspondence between the podiatrist and community workers (mainly practice and district nurses, who only make up a small part of the ‘team’) were said to add to the consistency of care provided.

Problems with patient-held records were also acknowledged. For instance, patients may lose records or not bring them to appointments. Furthermore, there was some uncertainty on the content (whether the language should be patient friendly or geared to healthcare professionals) and usage (whether the record should be filled out by the patient, the professional, a single lead professional or all involved). A recommendation that came out of the meeting was for the sharing of good practice for patient-held records and the development of a patient-held record to be used as a national template.

Although this would be a good step forward, at best it seems only a partial fix to the problems of multidisciplinary care. It is not just the writing we need to share but the whole record (including x-rays, scans and blood test results). What we really need is national infrastructure in the NHS, not just more talking or paper solutions.

The need for national infrastructure

Paper-based recording systems must be inherently flawed, given that we have been writing notes for so long and not yet fixed their innate problems. The infrastructure surely has to be information technology based, since it would enable the following.

- Everyone could see each other’s recordings of individual consultations.

- Professionals could communicate on the record electronically rather than by letter or ‘traditional’ email.

- Records would be available for hospital and community workers in the patient’s own healthcare establishments.

- Records could be accessed country-wide so that specialist referrals and episodes of care on holiday could all be included.

The National Programme for IT is thankfully now happening after many a false dawn but the challenges to be faced are immense in modernising our NHS. It is unlikely that a specialist area such as the diabetic foot will receive much attention in the first few years. In the interim, therefore, software solutions will need to be developed with the functionality to attach to the main computer spine when it is ready.

The first step may well be the agreement at a national level of what we need to record. The meeting recommendation to develop a record to be used as a national template is thus to be welcomed, if it can be brought to fruition.

In my view, an essential element of this new vision has to be an ability of the software to track the outcomes of our multidisciplinary care. We need to know when diabetes was first diagnosed, when we first started preventative care, when foot ulcers appeared and healed, if amputation was necessary and what the precipitating cause was. There is also a requirement to know what therapy works in getting ulcers to heal and to capture these data everyday, not just in individual research studies. Furthermore, we need to be able to look at data locally as well as to aggregate them at a national level. Therefore, it is necessary to collect data in a consistent way if we are to make real progress for all our patients by learning from the best services in the country.

National surveillance could be a major stimulus for change and would need central funding. Perhaps a model like the Surgical Site Infection Surveillance Service from the infection control world could be taken into consideration, with its use of confidential feedback on specific infection rates to individual teams while aggregating data anonymously at the national level.

Patient involvement

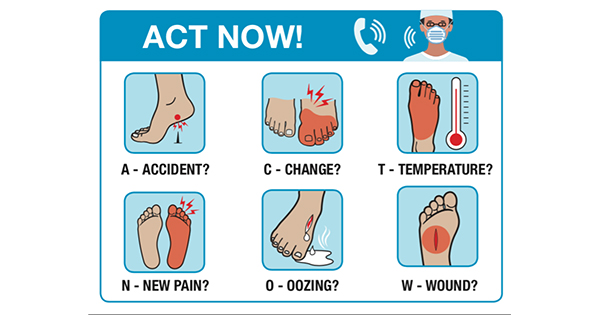

Getting patients involved in their care will continue to be a challenge in the future, but I think it would be fair to say that traditional patterns of working will become increasingly untenable as the number of patients rises and services struggle to meet the demand. Making use of the ability of some patients to undertake certain parts of their own care will need to become more commonplace, but these patients will still need to keep in regular contact with the lead professional. So why not harness communications technology to assist with this, such as the now-common camera phone, which enables patients to regularly send in pictures of their ulcers for monitoring? This might reduce visits to central podiatry clinics, while giving the patient and the community nurses more confidence to continue with a shared care plan.

Conclusion

Let’s not forget the ‘team’ but re-envision it as a network, which it is now and will continue to be in the future. By underpinning it with a proper communications system, we can maintain good working relationships while giving ourselves some structure and some nationally agreed rules of engagement to speed up referrals. Finally, within our network, we should properly acknowledge the professional at the hub of the service – the podiatrist – and cluster around him or her.