Public Health England’s annual reports provide the major and minor lower-extremity amputation rates for people living with diabetes. The Wessex region generally has a higher rate of amputations than the national average (Public Health England, 2019). Diabetic foot ulceration is the most common indicator for amputation. For this reason, the Wessex Cardiovascular Clinical Network (WCCN) decided to review the services it offered to see whether changes could be implemented to improve access to diabetic foot care services reduce the number of amputations performed annually.

Background

There is a registered population of over 133,000 people with diabetes across the two Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) in Wessex. It is estimated that any one time, 3,000 of these individuals will have an active foot ulcer. Diabetic foot disease resulted in over 5,000 hospitalisations during a 3-year period (2013–16), with the average length of hospital stay being 17 nights. During this period, there were 1,367 amputations across the STPs, of which 354 were major (above-ankle) amputations.

The total annual cost of managing foot ulcers in the community and acute foot disease in local hospitals was estimated to be in excess of £50m in 2017–18 (Public Health England, 2019). Just a 10% improvement in efficiency would, therefore, save £5 m.

The Wessex Diabetes Forum, a subgroup of the WCCN, has prioritised reducing amputations and reviewing and revising the foot care pathway to improve patient access to treatment for diabetic foot ulcers across the local STPs. To improve their understanding of the causes of variations in care leading to higher amputation rates, the WCCN is supporting comprehensive peer reviews of foot care pathways and services available in all of the Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) in the area. The hope is that sharing and learning from local peer review will improve services in CCGs across the region. The peer review process also has the support of Diabetes UK and NHS England. Patient feedback gathered through discovery interviews formed the first section of peer reviews across the Wessex NHS Trusts. These interviews had an emphasis on lived experience of care. This article focuses on patient feedback on foot care services across Wessex CCGs, describing patients’ individual views of their experiences of the foot care pathway and identifying common themes from the discovery interviews.

Methods

In Autumn 2018, a peer review of foot care services was conducted across the area of Hampshire, the Isle of Wight and Dorset led by Richard Paisey Consultant diabetologist Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust who an earlier foot care peer review in the South West. The population of Hampshire totals approximately 1.3 million people and in Dorset the population is estimated to be 770,000. There are eight NHS Trusts in Wessex. Each Trust was asked to provide between two and four patients with diabetes following amputation and/or foot ulceration for interview. To be eligible to participate, patients needed to have type 1 or type 2 diabetes with ongoing foot ulceration, healing ulceration and/or foot/lower limb amputation.

Consultant diabetologists in each Trust were written to, to ask them in conjunction with podiatry leads/teams to identify patients suitable for interview following amputation or ulceration of the foot. Patients were approached by the team to ask if they would be willing/interested in participating in discovery interviews, in order to help share their experience with peer review process. If patients were happy, they then gave consent to be contacted by the author as the person designated from the clinical network and trained in patient interviewing. The author then contacted each patient to discuss consent and if they wanted to proceed, they signed a form either physically or via email to agree to interview. Interviews often took place in the patient’s home at a designated time given by them due to mobility issues. Questions were drawn from an earlier peer review in the South West led by Richard Paisey.

The interviews were qualitative in nature. Participants were questioned using a discovery process in which open questions covering key areas of the diabetic foot care pathway were used as prompts for discussion. The findings were fed back as general themes. These interviews formed the opening element of the peer review process.

Participants

Patients were initially contacted by their clinician, who asked whether they were willing for WCCN staff to contact them about participating in a peer review. Seventeen selected type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients were then called and the purpose and details of the interview were explained. All of the patients contacted agreed to participate, however two withdrew: one due to illness and the other without giving a reason.

Consent was explained to each patient at the face-to-face interview or over the telephone. Signed consent was obtained prior to interview.

The majority of patients chose to be interviewed in their own home due to mobility issues related to foot disease. A smaller number chose to have a telephone interview. The full breakdown of patient interviews across the region is shown in Table 1.

Results

Some of the common themes to come out of the interviews are listed in Box 1. These themes are discussed in some detail below.

Challenges for patients

Various challenges were identified by participants. Several interviewees felt that there was a need for earlier access to diabetes education, with a much greater emphasis on foot care and the likelihood of foot problems. The feedback also highlighted the need for a greater awareness of any familial history of diabetes and the potential implications of this. A further area of importance for patients was the long-term effect of foot ulceration/amputation on their wider families, particularly on the mental and physical health of their carers.

Employment and footwear

Many of the patients interviewed had worked one or more manual jobs. They said this often necessitated wearing boots with ‘protective’ steel toe caps and/or steel soles for health and safety reasons. These types of footwear are a significant additional risk to the diabetic foot.

Employment and diabetes care

Patients described having busy working lives, with several being self-employed. They explained that the long hours they spent at work and a lack of job security had led to the importance of health appointments being secondary to their occupations. Due to the changing nature of employment and greater levels of self-employment, many patients felt that it was more important to keep working than to take unpaid leave and risk losing work contracts in order to attend health appointments.

Self-care

Several of the patients interviewed regularly worked away from home on a contractual basis. This was another reason why health appointments were often not attended on a regular basis.

One patient, who is now blind, described trying to dress an ulcer and provide self-care while working abroad. He reflected on this, as he is now unable to work in the job that he enjoyed and misses his colleagues and the social interaction that his job provided.

Employment and footwear

A number of the patients interviewed had worked on building sites for 30 years or more, and this required them to wear heavy-duty protective footwear with steel-capped toes. Interviewees felt that the rubbing of protective footwear in combination with neuropathy had led to further problems.

Many of the patients interviewed were now unable to work in their former jobs due to incapacity as a result of foot ulceration and/or amputation. Some were forced to take early retirement from professions in which they had enjoyed working for many years, with the consequent loss of social interaction and purpose derived from working life.

Depression and isolation, which required medication and counselling, were reported by several of the patients interviewed. Self-harm was reported in one case; this was fed back to the patient’s primary care team and the necessary help was offered.

One patient said he was not keen to wear specialist shoes as he felt they were ‘unfashionable’. Following discussions with his podiatrist, he has since agreed to wear them.

Family and/or carers

The effects of foot ulceration and amputation were felt not just by the patient, but also by the family. In one case, the patient’s wife had retired early to care for her husband, who was incapacitated by his diabetic foot ulceration. The physical and mental health issues of carers is well documented and also relevant to this group of patients.

Lack of early information about the serious effects of foot disease and importance of foot care

Some patients felt that healthcare professionals should put more emphasis on the serious effects that foot disease can have in the long term and how important foot care is in diabetes. Some interviewees felt they had been told about the serious nature of foot problems; however, at that point in their lives they were not sufficiently ‘tuned in’ to the implications.

Need for more powerful messaging on the implications of diabetes and diabetic foot disease

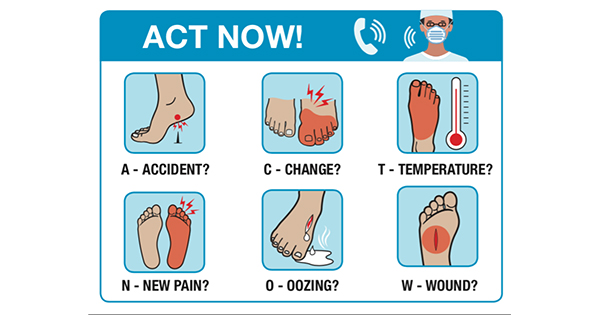

Diabetic foot disease is associated with modifiable risks of amputation and premature death (NICE, 2016). Important messages need to be delivered to employers that provide footwear to manual workers with diabetes. Messages to employers need to be stronger highlighting availability of foot wear suitable for a working environment via foot care services. Some examples of this were given during the foot care peer review process. Similarly, healthcare professionals must encourage patients to take greater responsibility for their care, using language that is easy to understand and providing practical tips on how to achieve perform good self-care.

Limitations

Limited time and resources meant that 14 patients in total were interviewed. The themes derived from the interviews are therefore general and the numbers too small to reach statistical significance. No interviews were performed in Basingstoke due to the short timescale and limited resources. However, it was considered that shared learning and themes from interviews across the rest of Wessex would also be relevant in Basingstoke. Despite these limitations, the entire spectrum of patient experience is valid and there were no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ responses to the open questions asked during the interviews. All of the patients’ responses were, therefore, of value in service improvement.

Discussion

The reviews will enable us to assess the quality and accessibility of foot care for people with diabetes and compare this with national and local standards. The successes and areas that need improvement in each CCG will be based on NICE guidance (NICE, 2016) and National Diabetes Audit outcomes, including the National Diabetes Foot Care Audit (NHS, 2018).

This was a small sample and would advocate similar patient interviews being embedded in an organisation’s delivery of care as part of their quality process. It is helpful to be undertaken by a team or individuals external to the clinical service. Although small in number, they set the scene and focus for each review. The only blame for outcome from interviewees was for not knowing more and not having sufficient early advice or being ready to note early advice in their patient journey. There were frustrations regarding delays, lack of access to early and ongoing education, repeating information, navigating the pathway and different clinicians having different treatment ideas for the same wound. Overwhelmingly, patients were impressed by the dedication, hard work and care provided by clinicians and support staff. Several interviewees were keen to see the reports from the reviews and would be reassured that the gaps they had experienced were recognised within a local action plan. Action plans will be followed up by the CVD network Diabetes Clinical Forum. The peer review reports, formal presentations and awareness raising of the foot pathway for everyone working in diabetes has established key trigger actions, including early and accurate diabetes and foot risk assessment, early referral into the foot pathway when risk identified and reinforced education and information.

Conclusion

A number of patients were interviewed across Wessex to capture information about their experience of the foot care pathway. Key themes were drawn from the interviews and discussed at each review. Patient experience reflects the real lived experience of individuals. It is for CCGs and all parties participating in the peer review process to consider and review care in light of this lived experience.