Diabetic foot ulcers are among the most devastating of all diabetic complications at a range of levels – social, physical, psychological and economic (Levin, 2002). People with active diabetic foot ulcers experience a reduction in quality of life (Franks and Collier, 2001; Evans and Pinzur, 2005) that is reported to be as great as that of amputees (Pinzur, 2004). Diabetic foot disease is the leading cause of non-traumatic lower-limb amputation in the developed world (Jeffcoate and Harding, 2003). Furthermore, people with diabetic foot disease are a significant burden to care-givers and healthcare systems (Boulton et al, 2005).

Various international consensus statements on the management of diabetic foot disease have been developed (International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot, 2003; American Diabetes Association [ADA], 2004). One major challenge lies in the prevention of ulcer recurrence (McInnes, 2003). Reulceration is a relatively common event, with rates of 35–40% over 3 years, increasing to 70% over 5 years (Apelqvist et al, 1993). Despite the frequency with which reulceration occurs in the diabetic foot, elements of this subject has been somewhat neglected in the literature, including the location on the foot at which the recurrent ulcer is situated.

Literature review

Six electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, British Nursing Index, ScienceDirect, Cochrane, EBSCO) were searched for articles that made reference to the location on the foot of diabetic ulcer recurrence. Only those published in English or Maltese were included in the search. The search terms (“diabetic foot ulcer recurrence, site of diabetic foot ulcer recurrence, location of diabetic foot ulcer recurrence,diabetic amputations, ulcer-free survival diabetes, repetitive ulceration”) yielded 128 articles. In addition, several medical and nursing journals, and relevant conference proceedings and symposia, were hand-searched but yielded no relevant material.

Titles and abstracts were assessed for any reference to ulcer site, narrowing the pool of articles to three: Mantey et al (1999), Connor and Mahdi (2004), Pound et al (2005). None of these studies on diabetic foot ulcer recurrence specifically reported the site of recurrence.

There is, therefore, a significant gap in the literature with regard to the site of diabetic foot ulcer recurrence, and such knowledge could influence management of this high-risk population.

Aims

The authors conducted a 6-month study of foot reulceration at a diabetic foot clinic in Malta, seeking to identify any association between reulceration, age, diabetes duration, sex and site of previous ulceration.

There is a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Maltese population (Savona-Ventura, 2002). Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports a type 2 diabetes prevalence of 10% for Malta – the highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Europe where a prevalence of 2–3% is common (Townsend Rocchiccioli et al, 2005; WHO, 2007).

Methods

The current study was undertaken at the diabetic foot clinic within the Diabetes and Endocrine Centre, St Luke’s Hospital, G’Mangia, Malta. Since completion of the study, the St Luke’s Hospital facility has been closed and the Diabetes and Endocrine Centre, and its associated clinics, relocated to the Mater Dei Hospital, Tal-Qroqq, Malta.

Patients are referred to the Diabetic Foot Clinic from the Diabetes and Endocrine Centre, from the community and from the Emergency Department. Individuals need to be referred to attend, but the clinic treats all levels of foot care from active diabetic foot ulceration to preventive care and advice.

Data from the diabetic foot clinic in 2004 show an incidence of foot ulcer recurrence of 32% (Azzopardi and Grixti, 2004), although the site of ulcer recurrence is not reported.

Ethical approval was gained from the Research Ethics Committee, University of Malta prior to commencement of the study.

Participants

All people with type 1 or 2 diabetes, over 18 years of age, attending the clinic for the management of recurrent foot ulceration during the 6-month study period (October 2005–March 2006) were identified for inclusion in the study.

People were excluded from the study if they fulfilled any one of the following criteria:

- Unwilling or unable to follow instructions and comply with the study protocol.

- Diagnosed neurological condition (e.g. cerebral vascular accident, spina bifida, multiple sclerosis).

- Diagnosed systemic disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis).

- Chronic alcohol abuse (alcoholism being a common cause of peripheral neuropathy).

- Neck, back or lower-limb trauma (due to associated sensory loss).

- Diagnosed pernicious anaemia (due to its impairment of wound healing).

- Receiving long-term steroid therapy (due to immunocompromise).

All those meeting the inclusion criteria (n=32) were invited verbally, and in writing, to participate in the study. All 32 people invited agreed to participate (100% response rate).

Data collection

Three sources were used to collect demographic information, and current and retrospective clinical data: an interview, a clinical examination and participants’ medical records. For the purposes of comparison, demographic and ulcer site data were also recorded for people who presented to the clinic with their first ulcer during the same period.

Participant interview

Participants were interviewed by the first author and a clinic podiatrist. Each participant’s age, sex, diabetes type and duration were recorded. Data were also collected on their previous ulcer (date, site and neuropathic/ischaemic/neuroischaemic classification) and the time in months from previous ulcer resolution to reulceration.

Clinical examination

Each participant was clinically assessed to provide information both on their current episode of ulceration (reulcerated) and to verify the data in their medical records on their foot ulcer history. In participants presenting with more than one ulcer, the largest ulcer was considered the most clinically significant (Jeffcoate et al, 2006) and data from that ulcer were recorded and used for analysis.

The site of reulceration was recorded for each participant as: (i) same site, same foot; (ii) different site, same foot; or (iii) other foot. Ulcers were classified as neuropathic, ischaemic or neuroischaemic.

Neuropathy was assessed using the Semmes–Weinstein 10-g monofilament (North Coast Medical, Campbell, CA). The inability to perceive a 10-g force applied at one or more site(s) was considered to be indicative of clinically significant neuropathy (Baker et al, 2005) and the ulcer was classified as neuropathic.

Ischaemia was assessed by palpation of pedal pulses and use of Doppler ultrasound where necessary. The absence of pedal pulses is associated with peripheral vascular disease (ADA, 2004) and participants with absent pedal pulses were classified as having an ischaemic ulcer.

In participants who failed to perceive a 10-g monofilament at one or more of the test site(s), and in whom pedal pulses were absent, the ulcer was classified as neuroischaemic.

Medical histories

Participants’ medical histories were investigated to confirm the information found during participant interview, especially with regard to the site of the previous episode of ulceration. The site of previous ulceration was recorded as for the current episode (same site, same foot; different site, same foot; other foot).

All the participants had been treated for their previous episode of ulceration at the diabetes foot clinic. Thus, all medical histories were available to the authors. The medical histories were all classified using the same investigative techniques used for the current study, and were recorded clearly.

Results

During the study period, 66 people presented to the authors’ clinic with active diabetic foot ulceration. Of these, 32 (48.5%) were ulcer recurrences, and all of whom were included in the current study.

All but one (31/32, 96.9%) participant with recurrent ulceration had type 2 diabetes. Participants had, on average, a diagnosed diabetes duration of 12.5 years (range 3–32 years).

Twenty (62.5%) participants were male. The proportion of men with reulceration was not significantly different to that of men who presented during the same period for their first episode of ulceration (20/34, 58.8%).

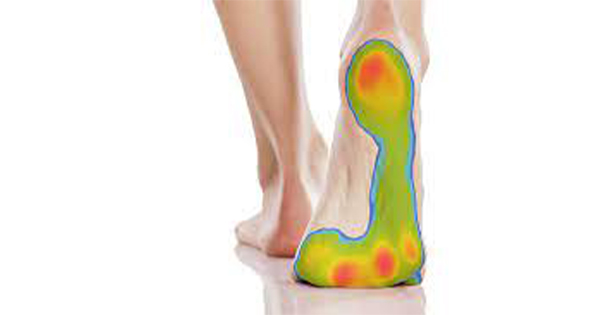

The mean (± standard deviation) age of those with recurrent ulceration was 62.3 ± 11.1 years. Those treated for their first episode of foot ulceration during the same period were 66.3 ± 13.7 years old. The difference between the age of those with recurrent and those with their first ulcers was not significant. Figure 1 shows the diabetic foot disease attempt to walk in a manner that avoids applying pressure to a previously ulcerated site. Consequently, pressure on the foot is redistributed and another site on the same foot becomes exposed to repetitive or excessive pressure, in turn disposing that site to ulceration. This suggests that biomechanical abnormalities may be especially important in determining the site of reulceration, and that further research into the redistribution of pressure on the foot following an episode of ulceration is warranted.

The data reported here with regard to sex, age, diabetes type and duration and reulceration are broadly consistent with the literature. The cohort included a preponderance of males, as has been reported elsewhere (Merza and Tesfaye, 2003). Here, the highest incidence of reulceration occurred in participants 55–64 years of age, a finding consistent with the literature (Reiber, 2001). A similar duration of diabetes (average 12.5 years) was found in the current cohort as has been reported elsewhere in the literature, with longer diabetes duration strongly associated with increased foot ulcer risk, as well as with neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease (Young et al, 1993; Day and Harkless, 1997; Girach et al, 2006). Here, a non-significant trend for increased duration of diabetes and reulceration was found.

Only one participant had type 1 diabetes. The over-representation of participants with type 2 diabetes is partially explained by the high prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Maltese population (WHO, 2007). Furthermore, Mantey et al (1999) and Pound et al (2005) both concluded that people with type 1 diabetes were not at significantly more risk of foot ulcer recurrence than people with type 2 diabetes.

Study limitations

Although conducted over a reasonable length of time, the sample size used here was small. For this reason, statistical significance was not reached for a number of interactions.

Conclusion

While the present study is limited by the size of the cohort, it contributes some data on the specific sites on the foot at which diabetic foot reulceration occurs – data notably absent from the literature. A time-window when risk of ulcer recurrence is highest was identified, during which intensive follow-up is warranted. The study also demonstrates that the most frequent site of ulcer recurrence is usually the same foot, but not the same site, and implicated abnormal foot biomechanics in this outcome.

If confirmed by other studies, the findings of this study may better direct service provision and clinical decision-making for those at risk of reulceration. Any reduction in reulceration will reduce the costs associated with active diabetic foot ulceration. Whether interventions to reduce ulcer recurrence would offset the cost of these preventative measures requires further study, but the benefits to the individual of remaining ulcer-free are clear.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the podiatrists, namely Phyllis Camilleri, Frances Attard and Carol Gobey, at the Diabetes and Endocrine Centre, Mater Dei Hospital, Tal-Qroqq, Malta for their assistance in conducting this research.