In 1987, a diabetologist colleague, Dr Roger Pecoraro, asked me, as an infectious diseases consultant, for advice on caring for his diabetic patient with a foot infection. After giving him some preliminary suggestions, I went to the literature to see what expert advice might be available on the subject. Although diabetic foot infection (DFI) was a relatively common clinical problem even then, there was remarkably little literature on the subject. Specifically, there were surprisingly few published papers; in fact, the first article presenting original research on the bacteria present in diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) was not published until 1976 (Louie et al, 1976).

Furthermore, the first prospective, randomised, control treatment study of DFI was only published in 1990 (Lipsky et al, 1990). The major available source of clinical information was textbooks, the most comprehensive of which was The Diabetic Foot (Little et al, 1983). The chapter on infection emphasised the importance of vascular insufficiency and gangrene, with little discussion of treatment, and few references specifically on DFI. It was not until the fourth edition (Little and Kobayashi, 1988) that a discussion of wound culture techniques was included. The general precepts for managing DFI in the 1980s were that: the major pathophysiological cause of DFIs was limb ischaemia (especially small vessel disease), leading to gangrene; DFIs were almost always polymicrobial, with obligate anaerobes playing a major role; nearly all patients with a DFI should be hospitalised and treated with broad-spectrum, parenteral antibiotic therapy; and, severe or apparently non-responsive infections usually required a lower-extremity amputation. Studies conducted since that time have shown that all of these concepts were largely incorrect.

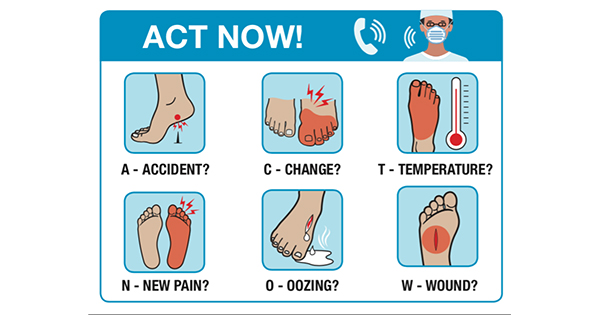

While the prevalence of diabetic foot disease (especially as a cause of hospitalisation) has increased, ulcers and infection, not vascular disease, are now the major underlying cause. At presentation, just over half of these DFUs are clinically infected. Even among those with an uninfected ulcer, recent data have shown that 40% will develop an infection within a year (Jia et al, 2017). Thus, infection develops in the majority of cases and it is usually the complication that leads to hospitalisation; unfortunately, for many patients this ends with a lower-extremity amputation. Clinicians (and patients) must, therefore, make efforts to try to prevent a DFU from becoming infected, if possible. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence on how to do this. Certainly, healing the wound removes the risk of becoming infected, so patients with a DFU should receive all standard wound care measures (e.g., debridement, pressure offloading and appropriate dressings).

For decades, many clinicians have also prescribed antimicrobial agents (either systemic or topical) in an attempt to either accelerate healing or prevent overt infection. There are no data to support the value of this approach, and it exposes the patient (as well as the healthcare system and society) to the risks of excessive antimicrobial treatment (Abbas et al, 2015).

Thus, the main issue in dealing with an infected DFU is how best to diagnose and manage infection. Fortunately, over the past 30 years there has been a remarkable increase in research in these areas. By the early 2000s, the increase in evidence-based data led two groups, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF), to commission the production of guidelines specifically devoted to the management of diabetic foot infections. Both were first published in 2004 and updated in 2012 (Lipsky et al, 2012); the IWGDF guidelines were most recently updated in 2015 (Lipsky et al, 2016). In addition to being published, these documents are freely available on each society’s websites (www.idsociety.org; www.iwgdf.org). Below, and in Table 1 (Uçkay et al, 2015), I will briefly summarise the key information provided in these extensive guidelines.

Classification

Before these guidelines, various classification schemes for diabetic foot complications described infection as merely being present or absent. The IDSA and IWGDF (working with their PEDIS scheme) defined infection by the presence of clinical (not microbiological) findings, specifically the classic characteristics of inflammation. Infections were then classified by severity, based on specific characteristics, as mild, moderate or severe. This information was designed to help clinicians decide which patients needed hospitalisation or surgical procedures, and what were the most appropriate antibiotic regimens (agents, route and duration of treatment). This classification scheme has since been validated in several studies as being predictive of the need for hospitalisation, and the likelihood of infection resolution or amputation.

Pathogens

In the 1980s, largely based on the paper by Louie and colleagues (1976) and the belief that DFIs were usually related to gangrene, it was widely held that DFIs were polymicrobial, with anaerobes playing a key role. Preliminary investigations in the late 1980s, and more robust ones conducted recently (Nelson et al, 2016), have made clear that for soft tissue infections a sample of tissue (collected by curettage or biopsy) provides more accurate microbiological data than a swab of the wound.

As more studies were conducted, it became clear that the predominant pathogens at presentation were aerobic Gram-positive cocci, most often with only one or two species cultured from the wound, with the most common being Staphylococcus aureus. Patients who had been hospitalised or recently treated with antibiotics more often had mixed infections, usually including aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, while those with gangrenous or ischaemic wounds often had obligate anaerobes. More recent studies from countries in warm climates in Asia and northern Africa have demonstrated that Gram-negative infections, especially with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (a waterborne species), are the most common pathogens. Furthermore, with the advent of molecular microbiology techniques in the past decade, we now know that there are more organisms present in DFIs (especially anaerobes) than we previously recognised. What is not yet clear is whether all of these isolates identified by these more sensitive techniques are pathogens that need targeted therapy.

When infection progresses contiguously to affect underlying bone, studies over the past decade have shown that a biopsy of the affected bone (taken at the time of surgery or percutaneously) provides the most accurate culture results. Generally, cultures of bone specimens contain fewer isolates than those of the overlying deep soft tissue.

Treatment

Virtually all clinically infected DFIs require antimicrobial therapy, and most moderate and severe infections also need some degree of surgical debridement of necrotic and infected tissue.

Antimicrobials

To halt the progression of infection in the confined spaces of the foot, it is important to start antimicrobial therapy as soon as possible, but only after appropriate specimens are collected. Since culture results are usually not yet available, initial therapy is usually empiric, based on the likely pathogens (as discussed above), as well as the local antibiotic resistance information.

For serious infections, when it is crucial to avoid failing to cover a pathogen, it is wise to start with a broad-spectrum regimen. This should almost always include agents active against S. aureus (including for methicillin-resistant species, when the epidemiologic circumstances suggest they are likely pathogens), common aerobic Gram-negative bacilli and possibly obligate anaerobes. For mild, and some moderate, infections, the antimicrobial regimen can usually be more narrowly focused on likely pathogens. Once the culture and sensitivity results are available the clinician should reassess the antibiotic therapy and, following the principles of antimicrobial stewardship (Lipsky et al, 2016), attempt to narrow the spectrum of the definitive regimen.

Two other key aspects of prescribing antimicrobials are the selection of route and duration of therapy. Some mild infections may be amenable to treatment with topical therapy, preferably with antiseptic, rather than antibiotic, agents (Dumville et al, 2017). Other infections generally require systemic treatment — oral for most mild and many moderate infections, but parenteral for severe infections (Selva Olid et al, 2015). In past decades, clinicians often treated DFIs with many weeks or even months of antibiotic therapy. The results of randomised controlled trials have now shown that treatment does not have to be more than 1–2 weeks for most soft tissue infections, or 6 weeks for osteomyelitis. Furthermore, recent (as yet unpublished) data have shown that even for complex musculoskeletal infections, treatment with oral agents is at least as effective, with fewer adverse effects, compared with intravenous therapy.

Surgery

Most DFIs require some debridement and many will require drainage. For less-extensive infections these procedures can be performed at the bedside, but large or deep wounds must usually be addressed in the operative theater. Before the advent of antibiotic therapy, surgeons often felt compelled to perform a major (often above-knee) amputation. In the past decade, the approach has moved toward more ‘conservative’ surgery, aimed at preserving as much of the foot as possible by minimising tissue and bone resection. In previous decades, osteomyelitis was almost always treated by surgical resection of the infected and necrotic bone. Studies over the past few years have shown that in selected cases antibiotic therapy alone is sufficient treatment (Lipsky, 2014). The other major surgical advance has been in revascularisation procedures (both open and endovascular), which are now conducted in more DFI patients with limb ischaemia, and performed earlier in their course (Hinchliffe et al, 2016).

Adjunctive therapies

In addition to antimicrobials and surgery, some clinicians have tried other types of treatment for DFIs. These include granulocyte colony stimulating factors, hyperbaric oxygen and, more recently, stem-cell therapies. Unfortunately, none of these have yet demonstrated clear evidence of effectiveness.

Conclusion

There has been a remarkable change in the diagnosis and treatment of DFIs in the past 30 years. We now have sufficient data to produce validated guidelines (in several languages) on management of these common, serious and costly infections. An important next step is to ensure these guidelines are more widely followed wherever DFI patients are managed. Healthcare workers in all settings should then audit key outcomes to ensure they are continually improving the care of their patients.