I wrote an editorial titled “What has QOF ever done for diabetic foot care” published in The Diabetic Foot Journal (Gadsby, 2010) in which I concluded that, since the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2004, there is evidence of a significant improvement in the recording of foot examination to detect neuropathy and the presence or absence of foot pulses in people with diabetes, with rates rising from 78–9% in 2004/5 to 91% in 2008/9. The editorial suggested it was likely that a new diabetic foot care-related QOF indicator would be introduced in 2011.

QOF changes from 1 April 2011

New QOF indicators, to be introduced on 1 April 2011, were published in March 2011 (British Medical Association and NHS Employers, 2011) – which is considerably later in the process than usual. A new indicator (DM 29) has been introduced. It is as follows:

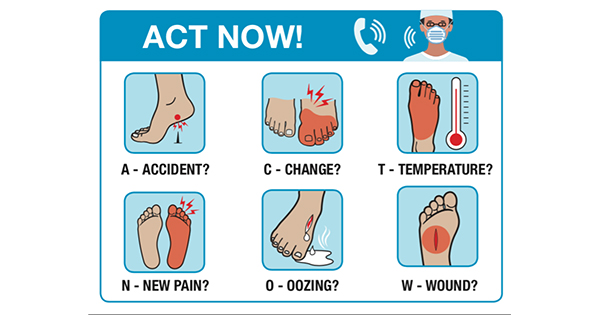

“The percentage of patients with diabetes with a record of foot examination and risk classification: 1, low risk (normal sensation and palpable pulses); 2, increased risk (neuropathy or absent pulses); 3, high risk (neuropathy or absent pulses plus deformity or skin changes); 4, ulcerated foot within the preceding 15 months.”

The minimum threshold to earn the available 4 points is 40% of patients with diabetes having had this risk screening, with the maximum being 90%.

From the previous edition of QOF, indicator DM 10 (the percentage of patients with diabetes with a record of neuropathy testing in the previous 15 months, minimal threshold of 25%, maximum of 90% to earn the full 3 points) has been retained; but indicator DM 9 (the presence or absence of peripheral pulses, worth 3 points) appears to have been “retired”. This means that the total points for diabetic foot care has risen from 6 to 7 for 2011/12.

The new indicator requires the practice to allocate a risk category based on foot inspection and examination for pedal pulses and peripheral neuropathy – which is a step forward from just having to feel the foot pulses and check for neuropathy. However, this new indicator does not require the practice to make the appropriate referral to the local foot protection clinic based on the level of risk. Referral to appropriately trained and resourced foot protection clinics is the intervention that reduces ulceration risk. In my opinion, an indicator that helps to achieve such a referral should be introduced.

Diabetes Quality Standards

The thirteen Diabetes Quality Standards produced by NICE (2011) were launched on 30 March 2011. These, along with the changes to QOF, will impact care of the diabetic foot over the coming years. Andrew Lansley, Health Secretary, said: “Quality Standards give an authoritative statement of what high-quality NHS health care should look like” (NICE, 2010). They will be the basis of commissioning led by the soon-to-be-formed GP commissioning consortia.

Diabetes Quality Standard 10 relates to care of the diabetic foot. It states that:

“People with diabetes with or at risk of foot ulceration receive regular review by a foot protection team in accordance with NICE guidance, and those with a foot problem requiring urgent medical attention are referred to and treated by a multidisciplinary foot care team within 24 hours.”

Each quality standard is underpinned by a statement about the structure, process and outcome of the quality measure. Then a description of what the quality standard means for each of four audiences (service providers, healthcare professionals, commissioners, patients) is given. The two structures of Diabetes Quality Standard 10 are:

- Evidence of local arrangements to ensure that people with diabetes with or at risk of foot ulceration receive regular review by a foot protection team in accordance with NICE guidance.

- Evidence of local arrangements to ensure that people with diabetes with a foot problem requiring medical attention are treated by a multidisciplinary foot care team within 24 hours.

The two outcomes listed are:

- Reduction in incidence of foot ulceration.

- Reduction in lower limb amputation rates.

Foot disease is the only diabetes complication that has a quality standard of its own, and this highlights the importance of this area. It should mean that commissioners are obliged to write contracts with providers to deliver these quality standards. The quality standard section on processes gives information as to how the standard should be audited, giving the commissioners clear statements on what needs to be done.

Hopefully, all of this guidance will ensure that diabetic foot care services are commissioned in every area. This should improve the standard of foot care for people with diabetes and help to deliver the reduction in foot ulceration and amputation we are all trying so hard to achieve.

– Roger Gadsby

As a diabetes podiatrist working across primary and secondary care, I have seen the benefit of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in driving up the profile of the diabetic foot. In the area in which I practice, Salford, in 1998 only 8% of people with diabetes had a recorded footing screening. We recognised that this was a serious deficit in our service and in the years that followed, with the impetus of QOF and NICE (2004), a podiatry-based foot screening service was established and, by 2009, >80% were receiving foot screening.

Data collected during audit also suggest that accurate screening, with appropriate risk stratification and a foot care programme can reduce the number of people who go on to develop an ulcer (Salford Foot Ulcer Unit, 2009). Unfortunately, the rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes (more than doubling between 1998–2009 [Diabetes UK, 2010]) made this model expensive and unsustainable. Now, a combination of the podiatry-led model and GP practice-based screening is being used in Salford. This shared system will continue until a centralised, integrated foot screening model, staffed by appropriately skilled healthcare professionals, can be introduced.

While QOF has achieved much, it concerns me that QOF foot indicators may be carried out in practices without close links to their specialist diabetic foot care service. The danger of it becoming a tick-box exercise is ever present, and QOF provides no incentive for onward referral.

Recently, a woman presented to our clinic with diabetic foot ulceration and underlying osteomyelitis. She reported attending her GP practice with the current episode of ulceration, a “foot screening” was undertaken through her stockings and she was described as “low risk”. The wound was not noted and no onward referral initiated. This case is anecdotal and, hopefully, an isolated case, yet it highlights the dangers of placing the responsibility for foot screening in the hands of healthcare professionals who are not adequately trained to undertake a basic assessment and are not familiar with the importance of rapid referral to the specialist diabetic foot team. As it is stated in Putting Feet First: National Minimum Skills Framework (Diabetes UK et al, 2011): “The healthcare professional who undertakes routine basic assessment and care [of the diabetic foot] should be aware of the need for urgent expert assessment and the steps to be taken to obtain it”.

My second major criticism of the QOF agenda is the ongoing screening of people who have already been identified as having “at risk” feet. Within a population like Salford’s – which has a diabetes population of 10000 – approximately 4000 people are in the preventative diabetic foot care programme, having regular podiatry care including assessment. These people do not need to be rescreened for a condition they already have and should be excluded from the screening model. Such an exclusion has a precedent in diabetic retinal screening; people who are in a treatment programme are exempted from ongoing retinal screening, although the practice still receives QOF points and clinical time is not wasted rechecking these people for their known condition. In these times of increasing resource pressure, in Salford alone such an exemption would save or shorten 4000 GP appointment slots every 15 months.

To conclude, I think that QOF has been of benefit for the diabetic foot; it has raised the condition’s profile in primary care and has driven up standards. However, the danger of not integrating the assessment into a whole-system approach is clear. A centralised call/recall system with close links to the main foot service should create an environment with sufficient safety nets to provide optimal care for people with diabetes. This, linked with the removal of people with previously identified diabetic foot disease from the screening process, should make the system more effective, manageable and affordable.

– Paul Chadwick