Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (BCHC) is a community Trust serving the population of Birmingham. The current population of Birmingham is approximately 1.1 million. According to the 2011 population census, 22.2% (238,313) of Birmingham’s population were born abroad. Thus the majority of its residents were born in the UK (77.8%), but this is less than the national average (86.2%) or the West Midlands average (88.8%; Birmingham City Council, 2011). Less than 10% of Birmingham residents (20,100) who were born abroad arrived before 1961, while 45% (106,272) arrived between 2001–2011. In the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the city saw an average of 27,000 people arriving each decade (Birmingham City Council, 2011).

Birmingham is considered a multicultural and multilingual city (Box 1). The increase to the population from people from other ethnic backgrounds is from migrants, asylum seekers or, on a temporary basis, tourists; many of these groups may need to access the NHS.

Looking at the population data from 2001 and 2011, the most marked increases were seen among Romanians, rising from 66 in 2001 to 1,433 in 2011. People born in Poland and Somalia arriving in Birmingham increased ninefold and those in born in China, Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Iran, threefold (Birmingham City Council, 2011). The most commonly requested languages in Birmingham in 2018 are Romanian and Polish.

The definition of “interpret” according to the Oxford English Dictionary (2018) is: “translate orally or into sign language the words of a person speaking a different language.” Interpreters are present at appointments to provide a service for patients, carers and clinicians. Failing to match a patient’s first or preferred language can impact on patient experience and health outcomes, possibly missing appointments and effectiveness of consultations. This may lead to patients having a misdiagnosis and ineffective interventions. The error rate when using untrained interpreters, including friends and family, may make their use more high risk than not using an interpreter. Equality of access to health services is identified as a principle in several Acts and documents, including;

- The European Convention on Human Rights (1952)

- The United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (1989)

- The Human Rights Act (1998)

- The Equality Act (2010)

- The Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice (2015)

- The BSL Act (Scotland) (2015).

The first time a clinician becomes aware that English is a patient’s second language and an interpreter is needed is likely to be on the referral form. When carrying out a new patient assessment, the patient will be given two appointment slots; one for the assessment, the second for treatment. In Birmingham, a letter is sent to the patient advising them a referral has been received and they have 3 weeks to book an appointment before it is deemed that an appointment is not needed and they are discharged. Often, another family member phones to book the appointment and say they will interpret. This can cause problems when it comes to answering medical history questions when they often answer for the patient thinking they know the answers. I once asked a patient about her medical history and the daughter answered informing me of breathing problems and heart problems. When she finished, her mother reminded her of leg problems that she forgot about and was contributing to her current complaint. Family involvement can also be a positive when the patient forgets dates of problems and diagnosis where things took place, but family members may remember them.

Appointments are often booked with the family members in mind so they can leave work early or it is their day off. This can be an issue, however, when the family member that speaks good English and knows the patient cannot make the appointment. A different family member who knows very little about the patient and may not be as fluent in English may accompany the patient instead. If an interpreter is booked, this problem is removed as they will ask the patient the questions directly. When carrying out a neurological assessment, it is essential to have the patient comfortable with the feel of the 10 g monofilament, not fearing it like a needle, and also that they understand the need to shut their eyes to respond if they feel the monofilament. Often, the patient will try and keep their eyes open, but more often the relative will prime the patient, asking “can you feel it now?” when they see the monofilament applied. This priming can give a false positive. If the clinician is trying to rule out a false positive by asking if the patient can feel the monofilament when one is not being applied, this must be relayed to the patient and relatives.

Family members may also phone to book emergency appointments when they say they have noticed a change in colour and increased pain in a toe. This happened to me with an Indian gentleman phoning up saying his wife who has diabetes has a red toe and was experiencing “too much pain”. An emergency appointment was offered that afternoon. She attended the clinic and her first words were “No English”. The phone call indicated that it was potentially an infected toe or the start of an ulcer. I then had problems obtaining a history to the problem and, fortunately on this occasion, a colleague was able to communicate with her about the problem. If the problem had been worse, it would have been much harder to communicate issues related to dressings, rest schedules and medication, as well as explaining to the patient the causes of an ulcer if debridement revealed one.

In November 2017, Birmingham Community Healthcare Podiatry Service used 48 interpreters, which included 12 different languages and three times using a British Sign Language (BSL) interpreter. The most popular being Urdu (14) Punjabi (10) Somali (5), as well as Bengali, Czech, Romanian, Pashto, Persian, Farsi, Gujarati, Arabic and Russian. Then, in December 2017, the service used 27 interpreters costing just over £700. Over the course of a year, between £5000–£8000 is being spent on interpreters.

It would, therefore, be fair to presume that the Podiatry service is similar to other health profession groups and the Trust would ensure that there is suitable training, guidance documents and policies on using interpreters. Unfortunately, this is not the case in my Trust. I have had training previously with British Sign language interpreters and deaf awareness, but not with interpreters. When searching the internet, I found that there is very little available anywhere in the country on this issue. The first document I found was from NHS England, entitled ‘Improving the Quality of Interpreting in Primary Care’. They had a working group and produced a draft document on the principles for high-quality interpreting and translating services (NHS England, 2015). Sadly, I could not locate a more up-to-date or finalised document. I then found a neighbouring Trust, the Black Country Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, has an Interpretation and Translation Policy (2015), which was due for a review in December 2017 (Black Country Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, 2015). The most recent document I found was from the British Psychological Society entitled ‘Working with Interpreters: Guidelines for psychologists’ (The British Psychological Society, 2017).

Before I talk about some of the recommendations of these guidelines, I want to mention about staff acting as interpreters and clinicians, therefore, considering themselves to be bilingual. I have already talked about how a colleague helped me with the patient in the emergency situation. In the guidelines I found (Black Country Partnership, 2015; NHS England, 2015; The British Psychological Society, 2017), they say it is acceptable that bilingual staff members can communicate information such as appointment times and providing directions to departments, but for anything more than that an interpreter is advised. If an interpreter is required, it is advisable to book one. Interpreting is a specialist skill — interpreters have their interpreting skills assessed and are subject to spot checks to ensure they are performing accurately.

Staff who consider themselves able to interpret into another language should also have their language competency level and interpreting skills assessed (The British Psychological Society, 2017). If a member of staff is being used in this role regularly, they must undergo training to continue doing so (The British Psychological Society, 2017). Many interpreting services expect that the interpreter has a degree in a relevant language. The staff member may be well educated, but in the English education system. I have even been asked by patients whether I have thought about learning another language. In Birmingham, this would depend where in the city one is located as to which language is needed.

If one considers that in two years studying GCSE French, one may be able to explain that they fell and broke their arm, this is vastly different to the vocabulary needed to ask a patient if they get claudication pain in their legs and what the symptoms feel like. In healthcare, closed questions (yes/no answers) should not be asked, rather open questions should be asked that encourage the patient to be more specific. The clinician may know some of the vocabulary used in an answer, but not all, and so an important detail needed for diagnosis may be missed.

Considering the different treatments people with diabetes may require, the use of an interpreter is vital so that the patient is informed about their current foot health and possible problems. This way they fully understand all that is being said by the clinician and, hopefully, late presentations with problems or even amputations will be avoided.

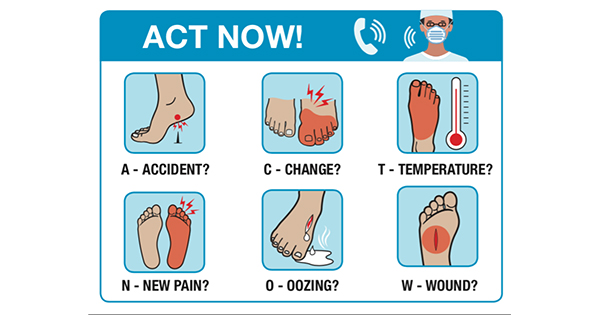

At the new patient assessment, the clinician may deem that this is the only time they need to be seen (patients at low risk). The education provided must include footwear advice to help prevent problems and daily foot checks to identify changes and how to seek help. If the patient is discharged back to the practise nurse, it must be considered how often this will take place or whether the patient should be advised to wash and dry their feet daily. Clear advice about recognising ulcer and pre-ulcer callus, as well as infections, is vital.

Footwear is also worth education. In many communities, the women of the house do not work and the vast majority of their time is spent at home wearing slippers or flip flops. The interpreter is, therefore, needed to explain the need to change footwear to accommodate ulcer dressings, to allow an insole to offload callus.

When reading the three guideline documents, they highlighted that a consultation when using an interpreter can be broken down into three sections – preparation, during the consultation and debriefing post-consultation.

Preparation

If required or requested by the patient to match the appropriate gender of the interpreter, this must be acted on. Having an interpreter that comes from the same country as the patient can help as this may reduce the chance of them speaking different dialects of the same language. If dialects are different, I have known interpreters switch to speaking another language to help the patient

to understand.

If possible, the interpreter should be briefed about the clinician’s job role and what the consultation/treatment today may involve. If an invasive procedure is necessary, it is worth checking that the interpreter is not squeamish. Photo identification of the interpreter should be checked, as well as the language they are going to speak to the patient in.

Preparation should be made for where the interpreter will sit; if possible, a triangle should be formed with the patient at the end and the interpreter to the side of the clinician. If the clinician completes paperwork/digital notes at a desk then examination should take place on a couch, with any chairs needed moved to maintain this arrangement.

With the patient present, the clinician should introduce themself and the interpreter, highlighting to the patient that the interpreter is bound by patient confidentially and they cannot repeat anything outside of the consultation. Also, the patient should be told that if they do not understand something then they should ask to have it said again in a way they can understand.

This may set some patients’ minds at rest in a smaller community where they may choose to withhold information for fear of others finding out. If the patient starts talking to other family members during the consultation the interpreter will translate this, preventing any missed information or questions the patient may have. It can also prevent the clinician feeling paranoid that others are talking about them.

At the same time, it is important to maintain a professional consultation, where the patient then does not start chatting to the interpreter about where they come from.

During the consultation

The patient should be spoken to directly, with the clinician maintaining good eye contact while addressing the patient, i.e., “How are you today?” This will avoid the tendency to ask the interpreter to ask questions, i.e., “How is he today?”

The clinician should speak clearly and slowly, pausing after each sentence to allow the translator to translate a manageable amount of information at a time. The clinician should also speak in simple, plain English, avoiding jargon, medical terms (unless explained afterwards) and acronyms where possible.

It may be useful to show the patient that the clinician wishes to test the blood flow and feel the pulses in the feet. The interpreter should also use the same hand signals and these are universal. Hand signals can be used to show that the clinician wants to check pulses in the feet by saying “like in your neck” (placing fingers to their neck (Carotid pulse)) and wrist (Brachial pulse), and then placing the clinician’s fingers on their wrist and then the patient’s feet. The interpreter should perform the same hand signals and, as anatomy is the same, the patient will understand what the clinician’s mean.

Explanations should be kept simple — longer and information-packed sentences may make it difficult for the patient to understand. The patient’s verbal and non-verbal communication should be observed and the clinician should be aware of their own verbal and non-verbal behaviours. The interpreter should also ask for clarification if they do not understand something that the clinician has said and personal scenarios should not be used to help convey a point.

At the end of the consultation, it would be beneficial to ask if there is anything else the patient wishes to discuss or wants clarification on. This should also be extended to other family members/carers that may be with the patient.

Future consultations/treatment plans should be discussed with the patient, as well as an explanation offered as to whether an interpreter will or will not be used for future visits. During the consultation, the clinician may have made an assessment that the patient has a sufficient level of English to no longer require an interpreter to be present at future visits.

It could be pointed out that a telephone interpreter (if available in the clinician’s area/Trust) could be contacted if difficulties arise. Police use a lot of telephone interpreters and a call is usually connected to an interpreter in 2–5 minutes. In Birmingham, over 90% of out-of-hours telephone interpreting is for Romanian patients accessing maternity services (this was discovered during an interview with Kavita Parmar, director of Word 360 Interpreting in January 2018).

Information provided by the clinician could also be supplemented with leaflets. The Diabetes Foot Action Group Leaflets are available in Arabic, Bengali, Cantonese, Polish and Urdu.

Debriefing post-consultation

The interpreter should have paperwork identifying the work carried out and will require a signature from a professional. It is worth having a quick chat with the interpreter to discuss how you both felt the consultation went. Questions that could be

asked are:

- “Did I go at the right speed for you to interpret?” n “Did I say anything that you found difficult to understand/interpret?”

- “Did I say anything or use non-verbal behaviours that could offend?”

The clinician should not forget to thank the interpreter as their role was vital in a

successful consultation.

Discussion

In Birmingham, using an interpreter to aid in a treatment consultation is becoming more and more frequent. When I asked the Director of Word 360 (Birmingham’s interpreting service) which language is hardest to get an interpreter for, I was surprised by her answer: “It’s not an individual language, but may be for a community where a suitably qualified interpreter/s are available to meet the demand.” Word 360 interpreting expect an interpreter to have a degree standard of education in the language they are interpreting and they are also given in-house training. In a new community, this is a challenge where there may not be someone with that education level who is trained in interpreting. This is true of Birmingham where there are new communities coming to live here from all over the world.

In areas that may be less diverse or rarely use interpreters, the clinician may wish to consider what has been said in this article and the following points:

- Does the Trust have a policy on using interpreters? Have you read it?

- Who organises the interpreters and is it clearly identifiable on diary sheets/computer bookings that you are expecting an interpreter?

- Document that an interpreter was used and if there was a job number in the patients notes? This may be useful if the patient wants clarification or to use the same interpreter.

- Clinicians should allow more time when using interpreters and, if possible, to incorporate time to brief and debrief the interpreter. More time is needed as each question goes from English-interpreted — answered by the patient and then interpreted back to the clinician. Guidance for psychologists in the UK suggests double the time (The British Psychological Society, 2017). Do you and fellow colleagues need more training to use translators more effectively?

Conclusion

Either due to budget constraints or patient not making clinicians aware English is not their first language, clinicians are expected to muddle through with broken English or end up not obtaining all the information required. This article aims to highlight how accurate information can be provided and received by patients with the help of an interpreter to have a more effective consultation/treatment. The future may lie in translation apps and programmes that translate in real time, but in view of the lack of guidance using interpreters, these systems are very much untested at present.