On February 26, 2014, the NHS Litigation Authority Chief Executive reported that clinical negligence claims had risen by almost 11% on the previous year. Expenditure on clinical negligence claims in England and Wales in 2012–2013 stood at around £1.25 billion (National Clinical Assessment Service, 2014). The rise of diabetes-related clinical negligence cases in the UK is due, in part, to the proliferation of ‘no-win no-fee’ firms, some of whom aggressively advertise their services.

As an expert witness podiatrist, I have observed a slow, but steady, increase in the number of diabetes-related referrals where clinical negligence was alleged to have taken place. These cases are usually, but not always, related to treatment episodes administered by an NHS podiatrist.

Role of the expert witness

There are two types of witness in law: (i) the lay witness is a witness to an act or action, but has no special knowledge pertaining to that act or action, (ii) the expert witness has a specific expertise in a particular field. The expert witness is instructed by a solicitor, barrister, or the court to provide expert testimony on a specific aspect or aspects of a case.

Expert witness reports tend to be one of two types: a screening or desktop report, and a court compliant report. The screening or desktop report is a short report, usually written to help the solicitor decide if there is a case to bring, or to defend. The court compliant report is an altogether lengthier report which will be used as evidence by the court.

Although the expert witness may be instructed by a solicitor, he or she has an overriding duty to the court (Ministry of Justice, 2015). They cannot, for example, write a biased report that shows the other side in a bad light. Although many cases do not reach court, some do, and any lack of impartiality is likely to be rapidly exposed by opposing counsel during cross-examination.

The expert witness podiatrist

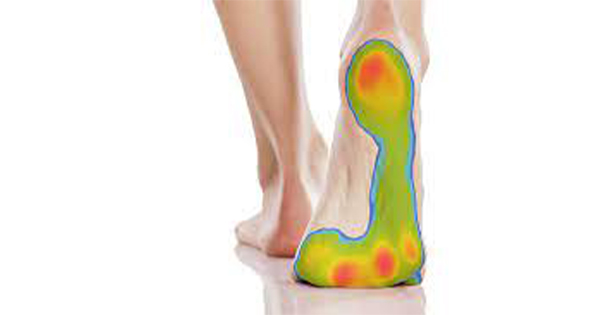

The expert witness podiatrist is expected to have an expert knowledge of the foot and lower limb, in illness and health. For cases related to the diabetic foot, a working knowledge of diabetes, diabetes-related conditions and complications, and of current treatment modalities for treatment of the diabetic foot is also required. A working knowledge of invasive procedures — specifically, in relation to diabetes, amputations — is an important part of the skillset of the expert. I have a special interest in gait and gait dysfunction, and this is also useful in some cases.

Arguably, an expert witness can rely on their professional expertise, with no further training needed to become an expert. However, it is generally accepted that academic qualifications should, as a minimum, be held at masters level (DiMaggio and Vernon, 2011). Additional training in forensics or civil law is advisable, but not mandatory.

To gain as full a picture as possible, a detailed medical history and prognosis from an expert witness podiatrist will be required by the legal teams, and additional input from vascular specialists, wound care specialists, and consultant physicians is common. Each expert, in turn, may recommend the consideration of the case by another expert.

Experience as an expert witness podiatrist

I have worked on diabetes-related clinical negligence cases for 5 years, being instructed by solicitors for the claimant and solicitors for the defence. The common denominators in almost all diabetes-related clinical negligence cases I have seen involving the lower limb are:

- Poor inter-departmental communication

- Poorly established referral pathways

- Poorly understood role of the podiatrist in diabetes care by other clinicians.

I have only seen a handful of cases in which the clinician him- or herself was responsible for a serious breach of duty.

Negligence may be claimed by any patient, at any time: the patient you were happily chatting to this morning may turn up at his/her GP surgery, and casually remark “the chiropodist cut me the last time I was there”. It can only take one careless, uninformed or mischievous remark, such as “the chiropodist used a scalpel on you?” to start a train of thought in the patient’s mind that can end in litigation, regardless of whether the claim is spurious. The stress that an internal investigation can generate — never mind court — can be overwhelming.

What can the clinician do?

There are some simple guidelines that all clinicians should adhere to. These are to be found in professional body standards (Health and Care Professions Council) and can be summarised as:

- Document everything

- Write clearly, with dates

- Sign everything you write

- Do not undertake any work outside of your competency, even if ordered to by a superior

- Remember that missing or badly-written notes are no defence in court.

The importance of note-taking

The first thing I ask myself when looking at a new case is: “Has the ‘SOAP’ format of note-taking been followed?” For those not familiar, SOAP is an acronym for:

- S for subjective: what did the patient say or tell the podiatrist?

- O for objective: what is the professional opinion of the attending podiatrist?

- A for assessment: has the feet or foot condition, together with anything else of relevance, been assessed and recorded?

- P for plan: what was the resulting treatment plan for that session, together with any advice given?

Good note-taking, using this system, gives the expert witness a picture of what happened on that visit. Indeed, it is possible to rebut a potential claim on the basis of one or two SOAP entries in the notes.

Example cases

Case 1

Several years ago, I was instructed by Welsh Health Legal Services to look at a case involving a man with type 1 diabetes, to see if there had been a breach of duty that may have constituted clinical negligence.

The claimant had complained, then instructed a solicitor to sue, because his foot had been cut by a podiatrist, leading to infection and, ultimately, partial amputation.

The podiatry notes were clearly written, and in the SOAP format. On the visit at which it was alleged the claimant had been cut, he had described his feet as ‘not bad’, and there was no mention of a cut to his toe or foot in the notes. Crucially, there would have been no reason not to mention a cut or nick, since this happens from time to time. Provided it is entered in the notes and a suitable dressing is applied, this would not constitute a breach of duty. On the next podiatry visit, there was no mention in the notes by the claimant of a previous cut to his toe or foot.

Examination of the claimant’s previous medical history revealed a previous digital amputation, a previous digital ulcer, a previous traumatic thermal injury, and a previous heel ulcer. It was also documented that the claimant had severe peripheral vascular disease. The medical records also showed that there was an established pathway, clearly understood by both the claimant and the podiatry team, for the claimant to be referred to his GP for antibiotics, as necessary.

In this case, the clear and concise podiatry notes suggested there was no breach of duty on the part of the podiatrist or podiatry team. The medical records provided evidence that, in this case, there was known underlying diabetic foot disease that, on the balance of probabilities, was likely the cause of any new developing lesion.

I reported back to Welsh Health Legal Services that, in my opinion, the care provided by that podiatry department before, during the index incident, and subsequently, was of a high standard, and did not constitute clinical negligence.

Case 2

In 2012, I was instructed to prepare a court compliant report that would examine the podiatry care provided to a 62-year-old claimant who was first diagnosed with diabetes in 1974. The claimant had issued a claim for personal injuries and other losses arising from allegedly negligent treatment provided to him between July 2008 and May 2009.

On August 12, 2008, the claimant underwent a partial transmetatarsal amputation of the right foot after developing gangrene. He subsequently underwent a below-knee amputation of the left leg in May 2009.

A professor of vascular surgery had raised questions about the adequacy of care provided by the GP, podiatrists, and nursing staff who saw the claimant from July 2008 onwards. In particular, he was concerned that no-one had sought a vascular specialists’ opinion.

April 2009 was identified as the cut-off point at which the claimant should have been urgently referred to secondary care, though he continued to be treated as a primary care patient.

The claimant had a history of obesity, hypertension, neuropathy and ischaemic heart disease. He had been an intermittently heavy smoker and drinker, and had a history of non-compliance with regard to podiatry appointments and diabetes review appointments.

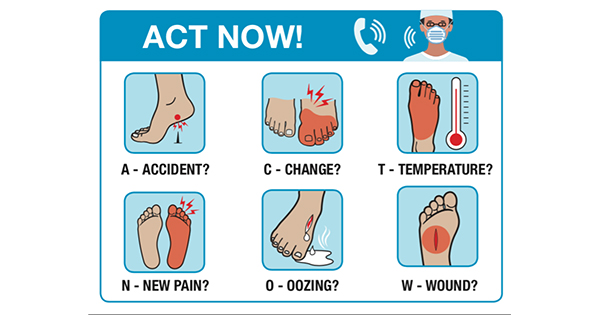

Podiatry clinic notes showed that the claimant presented with an ulcer on March 10, 2008. As per The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s (2004) guidance — Type 2 Diabetes Foot Problems: Prevention And Management Of Foot Problems — this presentation should have ensured that the claimant was referred to a multidisciplinary foot care team within 24 hours. That team would be expected, as a minimum, to investigate and treat vascular insufficiency. However, the claimant was simply given another routine appointment 1 month later. The fact that the claimant was not urgently referred to secondary care until he became seriously unwell was not disputed by any of the defendants. Images of the claimant’s feet are shown in Figure 1.

The vascular surgeon expert involved in the case was careful to point out that lower-limb arterial interventions on obese people with diabetes are very difficult, and the results are often suboptimal. A comment from him reads: “It is clear that during this stage [May 2009] the claimant’s life is very much in the balance.”

In my experience, this somewhat extreme example of what can go wrong if guidelines are not followed is not unusual. Currently, I have several similar active cases. This case was settled outside of court in favour of the claimant; I have no record of the eventual settlement figure.

Conclusion

I have discussed the role of expert witness and presented two cases that are typical of what lands on my desk. Case 1 is a spurious claim, easily dismissed. Case 2 is a serious case of negligence on behalf of the podiatrist, podiatry department and NHS Trust concerned. It is important to note in case 2 that, had the podiatrist concerned noted down that the claimant needed an urgent referral to secondary care — even if the suggestion had been refused by the department, multidisciplinary team, other agency, or the patient himself — they would likely have been exonerated. By not acting, the podiatrist became complicit in this case of clinical negligence.

Twenty years ago, clinical negligence was something occasionally reported on the news when a high-profile case had been settled. Even 10 years ago, clinical negligence was a phrase we might have heard occasionally, perhaps in hushed tones in the hospital car park or canteen. Today, clinical negligence claims — whether proven or not — are relevant to all clinicians.