Originally described by Jean-Martin Charcot as characteristic changes of the foot in tertiary syphilis in 1883, the ‘Charcot foot’ was described as a complication of diabetes just over 50 years later (Jordan, 1936). The diagnosis of Charcot is based on a clinical history and both clinical and radiological findings and the demonstration of fractures or dislocations in one or more bones of the foot in the absence of evidence of bone infection (Rogers et al, 2011).

Although an X-ray is the initial imaging recommended, obvious changes may be absent. Inflammation plays a key role in the early clinical findings along with oedema, erythema, warmth, and more than a 2oC difference in local temperature in comparison with the contralateral limb, all of which are typical symptoms of an active Charcot foot.

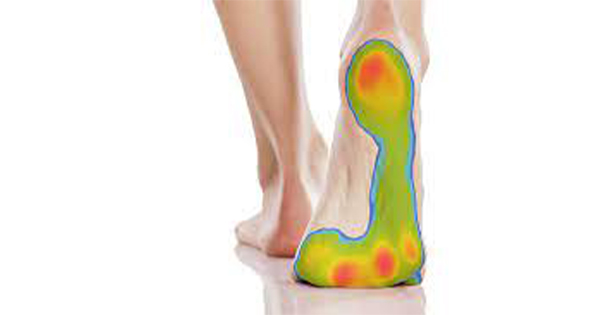

There is a general consensus regarding the causes of Charcot in people with diabetes, namely; sympathetic nerve damage causing hyperaemia and osteopenia, loss of sensory protective sensation and abnormal loading due to motor neuropathy with or without the effects of connective tissue glycation (Gazis et al, 2004).

Connective tissue glycation occurs as a result of higher levels of advanced glycated end products (AGEs) due to hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress. This can lead to altered function of tissues (skin, muscle and tendon).

Charcot neuropathic arthropathy is frequently associated with a prolonged healing time and risk of ulceration, infection and amputation, and the multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to ulcer and amputation prevention has been well-documented; aiming to improve quality of life (Yazdanpanah et al, 2015) and reducing amputations rates (Krishnan et al, 2008; Tseng et al, 2011; Rubio et al, 2014; Wang et al, 2016). The evidence supporting the importance of MDT working for Charcot management is highlighted in two recent literature reviews (Musuuza et al, 2019; Albright et al, 2020). NICE and SIGN guidelines highlight the use of a MDT to manage the pathway of care, with the recommended professionals within the MDT, including: podiatrist, diabetes physician, orthotist, diabetes nurse specialist, vascular surgeon, orthopaedic surgeon and radiographer (SIGN 2017; NICE 2019). Additionally, a consensus statement indicates this should ideally include dieticians, GPs with a specialist interest in diabetes, infection specialists, patients and their families/carers, pharmacists, psychologists, social workers and wound care-trained nurses (Munro et al, 2021).

The following case study will focus on the treatment of patient who attended the MDT for management of a Charcot foot and ulceration, highlighting their journey though the referral pathway and concentrating on the integrated approach to patient care.

Case study

Mr B attended the podiatry MDT in March 2017 following referral from the emergency department (ED) for a swelling of the left ankle/calf for approximately six weeks with no report of any precipitating trauma. The ED history indicated this had been ongoing since January 30, 2017, but had recently become more swollen and following a consultation with his GP, he was referred to ED for a suspected deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the left lower leg. He underwent a Doppler ultrasound of the left leg, which was negative for a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and, therefore, an X-ray of the left foot and ankle was requested. The radiologist report indicated marked osteoarthritis at the left ankle and subtalar joints with a pes planus deformity and dislocation at the talonavicular joint with bony debris around this site (Figure 1).

The findings were consistent with Sanders-Frykberg type 3 Charcot arthropathy. Less marked degenerative disease was seen at the naviculo-cuneiform and first tarsometatarsal joints. Mr B was then referred to the orthopaedic plaster team where he was fitted with an aircast offloading boot and a referral made to the diabetic foot clinic (DFC) as per local guidelines. An appointment was made for the following week.

Mr B’s medical history included type 2 diabetes, since 2011, with associated peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity. His HbA1c at the time was 42 mmol/mol and had generally been under 50 mmol/mol according to his blood tests.

Clinical history

Mr B attended the DFC with an oedematous and erythematous foot with a temperature difference of 3.4oC. The clinical presentation, X-ray report and temperature difference confirmed a midfoot Charcot at the talonavicular joint. There had been a rub over the medial midfoot prominence of the foot associated with the Charcot deformity and he had subsequently developed an area of ulceration. He was placed into a moonboot that was able to accommodate the Charcot deformity and semi-compressed felt (SCF) was used to help offload the area from the confines of the boot. Neurological assessment had 0/10 sites detected with a 10-g monofilament (an instrument used commonly for screening for loss of protective sensation in the foot) and vascular assessment noted all pedal pulses were palpable with no evidence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). A follow-up appointment was made for 1–2 weeks to review.

Between his MDT appointments Mr B had noticed increasing redness around the ulcer site and was prescribed 1-g Flucloxacillin QDS by his GP. Unfortunately, this did not settle and he presented to the ED where he was admitted to hospital and commenced on intravenous (IV) antibiotics. He was reviewed by the podiatry team while an inpatient and then followed up in the MDT clinic post-discharge where his ulcer improved and his Charcot foot settled. By July, the foot was intact, however, the temperature difference remained 2.5 ºC suggestive of ongoing active Charcot and was not deemed to be suitable for a referral to the orthotist service for footwear at this time and a new moonboot was supplied. He was continually reviewed by the MDT for temperature monitoring at this time.

Mr B was readmitted to hospital just before his review appointment when he was reviewed by the podiatrist and diabetes consultant. The wound had deteriorated again with the underlying joint capsule visible and surrounding erythema (Figure 2). The foot and ankle was X-rayed showing ongoing sclerosis and destruction of the talo-navicular joint (Figure 3) with collapse of the talar dome (Figure 4). A recent swab confirmed the presence of Meticillin-resistant (MRSA) and Streptococcus Group G and he was commenced on IV vancomycin on the advice of the microbiology team. Mr B was not systemically unwell although his C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 183 and, therefore, he was discharged with linezolid 600 mg BD.

During the first few months of 2019, the wound started to improve. However, in May 2019 it deteriorated again resulting in excessive bleeding with the presence of hypergranulation tissue (Figure 5). Mr B also had two visits to the ED due to worsening infection and was admitted again for IV antibiotics. At this point, the orthotist was consulted to consider any additional offloading devices they could offer. An appointment was arranged for new footwear in addition to a ankle orthotic, known as a German anklet.

The wound then began to improve again but soon had a setback following trauma directly to the wound. This resulted in excessive bleeding and increased infection. Clinically, the wound was infected and hypergranulating which required treatment with 75% silver nitrate; additionally the joint capsule/fascia was exposed. There was a suggestion of deeper infection over the coming months with bone palpable and pus and bone samples were collected, suggesting underlying osteomyelitis. The ulcer was undermining and highly exuding. He was continued on oral flucloxacillin and ciprofloxacin based on recent tissue samples. Mr B was offered various offloading treatments including total contact casting (TCC), but declined and preferred to continue with the boot and felt offloading. Due to the significant deterioration in the wound and increasing medial prominence, in September 2019, Mr B was advised that due to the continuing infection flare-ups and significant depth of wound and increased deformity of the foot, there was a high likelihood of a major amputation.

There was further difficulty with obtaining a suitable offloading device, due to the change in foot structure and this proved to be a challenge as this only increased the risk of increased pressure over the medial prominence of the foot and, thus, more risk of wound deterioration. Mr B was seen by the MDT with the specialist podiatrist, consultant and orthotist and a decision made to cast for an anklet, ankle boot and total contact insole (TCI). Due to the deformity and patient compliance, he continued with his othotist footwear and SCF as an offloading option.

Over the 34 months it took to consolidate, Mr B was reviewed in the diabetic foot clinic he had a total of eight ED visits with three admissions for intravenous antibiotics due to foot infection ranging between 2 and 14 days. Additionally, multiple courses of oral antibiotics including Linzolid, ciprofloxacin and flucloxacillin were provided both by the acute MDT and followed up with the GP on the advice of the consultant physician for ongoing infection management. During his inpatient stays, he was reviewed by the DFC MDT 91 times, who communicated with the ward and community nursing team for ongoing management of foot ulcer dressings, offloading and antibiotics. Furthermore, consultations with the microbiologist were required for antimicrobial guidance in addition to ongoing oral antibiotic prescriptions provided by his GP.

Due to the refusal to use any of the suggested offloading devices to help prevent deterioration, the medial prominence became larger, which resulted in additional pressure and difficulty finding suitable devices for him to wear.

Once Mr B was fitted with his anklet (Figure 6), the wound began to improve again and progressively got smaller. Exudate levels reduced and the wound size reduced. A decision to use steri-strips to encourage the undermining tissue to fill in was started and helped facilitate the closure of the wound.

Discussion

By the time Mr B was fitted with his German anklet in October 2019, the wound had gone onto fully reepithelialise and has remained intact to the date of submission (Figure 7). This case study outlines the importance of team work in involved to prevent significant morbidity from all areas of the MDT, ranging from the acute based diabetic foot MDT to community Podiatry and nursing, ED staff and inpatient team despite poor patient compliance.

In addition to the NICE and SIGN guidelines of MDT members, this patient significantly benefited from a wider range of health professionals in both in the acute and community setting including; microbiologist, GP, clinical support workers, however, the key to a good outcome in this case is due to the inter-professional team working across different departments and hospital sites. Charcot neuropathic arthropathy, even once in remission, can still continue to be problematic due to bony prominences resulting from fractures and dislocations which are likely to rub and ulcerate, often requiring ongoing management and risk of infection and amputation. In this case, the effective working of the MDT has ensured this patient did not require an amputation and continues to remain mobile and ulcer-free.

Conclusion

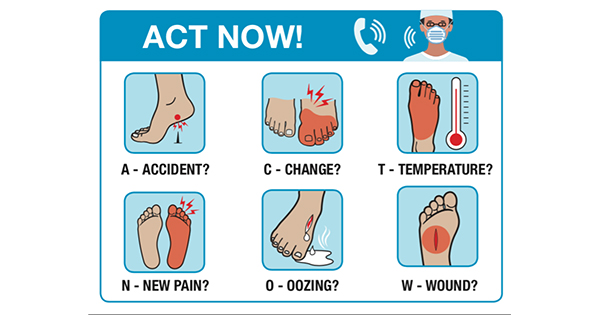

Although Charcot foot is relatively rare, it can be a devastating condition, more so the longer it takes to diagnose. Often, patients are commonly treated or investigated for cellulitis, DVT or gout thus delaying diagnosis and increasing the risk of further deformity and ulcer/amputation. Any person with diabetes with peripheral neuropathy attending their GP or ED with a red hot and swollen foot should also have a differential diagnosis of Charcot investigated and treated accordingly with local guidelines.