There were 7545 major amputations in people with diabetes in England between 2015 and 2018 (Public Health England, 2019), and there is a postcode lottery for amputation rates, with a sevenfold difference between geographical locations even after correcting for age and ethnicity (Holman et al, 2012; Jeffcoate et al, 2017). It is known that 84% of lower extremity amputations result from complications of a foot ulcer (Pecoraro et al, 1990). In theory, these amputations are avoidable if ulcers are either prevented or healed very quickly.

Why are there so many major amputations in diabetes?

During their lifetime, one in three people with diabetes develop an ulcer, as they are susceptible to minor trauma causing breaks in the skin, which are not recognised because of neuropathy. These lesions are also difficult to heal because of reduced circulation due to diabetes. Foot ulcers are highly susceptible to infection, which can spread rapidly, causing overwhelming tissue destruction and wet gangrene, necessitating major amputation. It is important to be aware of the speed with which infection can evolve: a person living with diabetes can have an intact foot on a Monday, a break in the skin on Tuesday, infection of the foot on Wednesday, gangrene on Thursday and undergo a major amputation on Friday. The faster the infection spreads, the greater the tissue loss. In these circumstances, “Time is Tissue!” People with diabetes may also come to amputation because of a very severe reduction in blood supply to the foot per se, leading to dry gangrene. Thus, severe infection or severe ischaemia can lead to limb- or even life-threatening conditions.

What can be done?

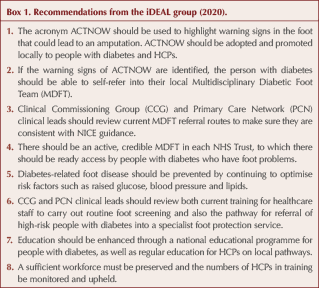

The iDEAL (Insights for Diabetes Excellence, Access and Learning) group is a multidisciplinary team of diabetes specialists with a keen interest in improving diabetes care outcomes across the UK. It has published a position statement titled Diabetes and Foot Care Assessment and Referral, which puts forward a series of recommendations to improve foot care for people living with diabetes (Box 1), and to improve education both for these people and for those who care for them (iDEAL group, 2020). An important aim is to reduce the unacceptable burden of major amputations.

The position statement has put forward a goal of reducing the number of major amputations in people with diabetes by 50% within 5 years, a target that has been achieved by multidisciplinary diabetic foot teams (MDFTs) when foot care was optimised (Edmonds et al, 1986). This 50% reduction of major amputations was taken up as a target in the St Vincent Declaration in 1989 (Piwernetz et al, 1993), which set goals for the healthcare of people with diabetes, but sadly the 50% reduction has not been achieved on a population level.

How can we achieve a 50% reduction in amputations?

There are four action points:

1. To heal ulcers as quickly as possible.

2. To prevent the development of ulcers in the first place.

3. To educate people living with diabetes, healthcare professionals (HCPs) and MDFTs.

4. To maintain a sufficient, sustainable and supported workforce.

1. Healing of ulcers

The urgent aim is to prevent amputations by getting ulcers healed as quickly as possible, and to treat infections and ischaemia rapidly, before gangrene develops.

If a person with diabetes develops an ulcer, it is important that urgent and expert treatment is easily available, and ideally that this is delivered by specialist care from a MDFT. Even in the COVID-19 pandemic, it is essential to recognise that foot ulcers are serious and can be limb-threatening. Those who develop an ulcer should be referred for urgent multidisciplinary care. Indeed, NHS England and NHS Improvement (2020) stipulated in its clinical guide for the management of acute diabetes patients during the coronavirus pandemic that multidisciplinary diabetic foot services may need to continue at full capacity.

Delay in reaching such specialist care can take place in three situations along the person’s journey:

- Delay by the person with diabetes in seeking and reaching care.

- Delay by HCPs in referring to specialist care.

- Delay in actually accessing care from the MDFT.

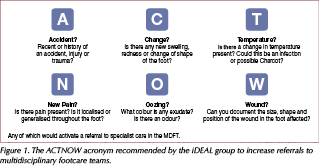

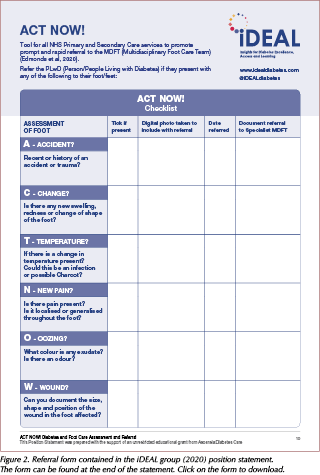

A lack of knowledge leads to a lack of urgency, and both people with diabetes and HCPs may not appreciate the warning signs of an amputation and the need for foot problems to receive urgent attention (Pankhurst and Edmonds, 2018). An acronym, ACTNOW (Figure 1), has been devised to help people with diabetes and HCPs recognise the warning signs that should trigger referral to specialist care. An ACTNOW checklist to aid referral is illustrated in Figure 2. This approach is similar to the use of the acronyms STOP and FAST, which were successfully associated with the campaigns to inform the public of the early warning signs of heart attack and stroke.

Recommendation 1: The acronym ACTNOW should be used to highlight warning signs in the foot that could lead to an amputation. ACTNOW should be adopted and promoted locally to people with diabetes and HCPs.

Recommendation 2: If the warning signs of ACTNOW are identified, the person with diabetes should be able to self-refer into their local MDFT.

Such direct access may not be easily available, especially in COVID times, but it remains an aspiration. However, the person with diabetes should have initial access to an HCP in primary care or in community podiatry, nursing or tissue viability teams for urgent advice, and this initially may be by telephone (Stafford, 2020). The HCP can then assess the situation and decide whether the individual has a limb- or life-threatening foot problem that needs immediate referral to the MDFT, an ulcer that needs urgent referral or a foot complication that can be treated in the community and at home, especially if the person does not want to go to the hospital MDFT.

Telemedicine has facilitated virtual contact between HCPs and MDFTs, expediting joint decisions about the need for referral and, subsequently, allowing MDFTs to keep in virtual contact with both the person with diabetes and the HCP on follow-up (Rogers et al, 2020). Telemedicine has also enabled contact between HCPs and people with diabetes who are cared for in the community and primary care. However, amid this rapid expansion of the use of telemedicine, many people with foot complications will not have access to this form of communication. Therefore, it is very important to have clarity of referral pathways in primary care to support people with diabetes along the optimum pathway to specialist help. In its NG19 guideline, NICE (2015) advocates that a person with diabetes who has a new ulcer should be referred within one working day to specialist care and for triage to take place within one further working day. The ACTNOW acronym supports this but also highlights other warning signs that should activate referral apart from ulcer. The NICE guideline also indicates that people with diabetes who have limb- or life-threatening foot problems – such as ulceration with limb ischaemia or with fever, any signs of sepsis, or a deep-seated soft tissue or bone infection or gangrene – should be referred immediately to acute services and the MDFT informed.

Recommendation 3: Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and Primary Care Network (PCN) clinical leads should review current MDFT referral routes to make sure they are consistent with NICE guidance.

Recommendation 4: There should be an active, credible MDFT in each NHS Trust, to which there should be ready access by people with diabetes who have foot problems.

For these referral pathways to be successful, an MDFT should be available in each NHS Trust hospital. Unfortunately, the 2018 National Diabetes Inpatient Audit, which covered the structures of care that are fundamental to achieving the standards of safe, effective inpatient diabetes care, showed that one sixth of hospital sites (17.3%) did not have an MDFT (NHS Digital, 2019a).

2. Prevention of ulcers

Recommendation 5: Diabetes-related foot disease should be prevented by continuing to optimise risk factors such as raised glucose, blood pressure and lipids.

Ideally, neuropathy and vascular disease should be prevented by excellent blood glucose control. This is not easily achievable at present but it should remain an ambition to achieve as good blood glucose control as possible, which could at least slow the onset of neuropathy and protect people with diabetes from being susceptible to minor trauma.

Recommendation 6: CCG and PCN clinical leads should review both current training for healthcare staff to carry out routine foot screening and also the pathway for referral of high-risk people with diabetes into a specialist foot protection service.

If a foot has already developed neuropathy and ischaemia, and has thus become at risk of ulceration, the way forward now is to prevent ulcers by protecting the foot. Therefore, people with diabetes should be screened annually for risk factors leading to ulceration. It is important that all people with diabetes undergo screening in primary care by trained professionals, and recently the Pharmacy Quality Scheme has encouraged pharmacists to ask people with diabetes to check whether they have had their annual foot and eye screening when they present with a prescription (Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee, 2019). Furthermore, community pharmacies could become a recognised point of contact where actual screening could be carried out by trained members of the community pharmacy team, if a national community pharmacy service is funded by NHS England. The community pharmacist should then be able to refer high-risk individuals to the local foot protection team without delay and, by using the ACTNOW tool, be able to refer any foot identified as being in danger of amputation directly to the MDFT, if included in local referral pathways. This streamlined process will be considerably beneficial to people with diabetes who, for reasons such as social deprivation, may not be able to or have the means to self-refer to the MDFT.

Regardless of how or where people with diabetes who have high-risk feet are identified, they should be followed up by a foot protection service. The National Diabetes Foot Care Audit indicated that 9 in 10 providers of foot care have a foot protection service, which has primary responsibility for the care of people at high risk of new ulceration and thus for the prevention of ulcers (NHS Digital, 2019b).

3. Education

Recommendation 7: Education should be enhanced through a national educational programme for people with diabetes, as well as regular education for HCPs on local pathways.

Improvement of foot care is dependent on a well-informed and educated body of people with diabetes, HCPs and MDFTs. A national education programme should be established, with practical information in an illustrated, practical handout for all people with diabetes about foot self-care and checks from diagnosis onwards. Also, there should be increased access to education in foot assessment and urgent referral for all HCPs working with people with diabetes.

4. Maintaining a sufficient sustainable and supported workforce

Recommendation 8: A sufficient workforce must be preserved and the numbers of HCPs in training be monitored and upheld.

In order to reduce the number of major amputations and achieve the target 50% reduction within 5 years, it is imperative that there is a properly staffed workforce of HCPs. However, since the removal of NHS student bursaries in 2017 in England and Wales, programmes for podiatry and prosthetics have struggled to attract and retain enough students to enter the profession for succession planning to meet the needs of people with diabetes in the future (Council of Deans of Health, 2019).

The podiatry workforce can only be maintained by reversing the decline in podiatry student numbers. The Council of Deans of Health and the College of Podiatry have called for the introduction of a maintenance grant for healthcare students and full payment of tuition fees for podiatry students in England (Council of Deans of Health, 2019). In return, the graduate would work for NHS services post-qualification, as has been rolled out in Wales.

Conclusion

The impact of these recommendations will be to accelerate the healing of ulcers in people with diabetes and hence reduce the number of foot infections, hospital admissions and major amputations. If the recommendations in this position statement are put into practice, the iDEAL group believes that a 50% reduction in major amputations in people with diabetes within 5 years is achievable. The present situation has gone on for far too long and has resulted in an unacceptably high number of major amputations that could be prevented. This can no longer be tolerated: ACTNOW and save feet!

Quantifying the risk of worsening glycaemia, and how should healthcare professionals respond?

22 Apr 2024