| Learning points |

| • The co-diagnosis of diabetes and cancer is common. • Diabetes increases the risk of poorer outcomes in people with cancer. • There is no good data to suggest that tight glycaemic control is beneficial. • Screen all patients undergoing systemic anti-cancer therapy for diabetes with HbA1c and random plasma glucose tests. • Avoid extremes of hypo- and hyperglycaemia. • Metformin is useful and may improve outcomes. • Monitor and treat post-prandial glucose levels in patients on glucocorticoid therapy. • Monitor for new-onset type 1 diabetes or diabetic ketoacidosis in people on immune checkpoint inhibitors. • Discuss withdrawal of non-essential treatment in patients with limited life expectancy. |

Links between diabetes and cancer

Diabetes and cancer appear to be linked, independent of obesity and other risk factors common to the two conditions.1 Meta-analyses show that the relative risks of cancer in people with diabetes are greatest for the following:2,3

● About two-fold or higher:

- Pancreas.

- Liver.

- Endometrium.

● Moderate (about 1.2–1.5-fold):

- Colon and rectum.

- Breast.

- Bladder.

● Conversely, diabetes appears to be protective against cancer of the prostate.4

Pre-existing diabetes increases risk of mortality from cancer. Meta-analyses suggests that diabetes is associated with an approximate 40% increased risk of mortality in patients with cancer compared with normoglycaemic individuals.5

Possible pathogenic mechanisms

Hyperglycaemia: Rapidly proliferating tumour cells consume glucose at a high rate compared with normal cells, and hyperglycaemia may contribute to cancer by way of providing energy at a cellular level.6

Hyperinsulinaemia is associated with type 2 diabetes, and leads to reduced hepatic synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), leading to increased free levels of oestrogen in both men and women, and increased levels of free testosterone in women. The association of hyperinsulinaemia with cancer appears highest with breast and endometrial cancers.7

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1): Insulin also appears to increase hepatic production of IGF-1, which promotes cellular growth. The insulin receptor is structurally related to the IGF-1 receptor and, at high concentrations, insulin may also activate the IGF-1 receptor. IGF-1 activates multiple signalling pathways known to be implicated in cancer pathogenesis. In large epidemiological surveys, elevated circulating insulin and/or IGF-1 levels were associated with colorectal cancer.8

Diabetes therapies and cancer risk

Metformin may provide some protection from cancer in epidemiological studies, possibly through modulation of insulin resistance and hence reduced circulating insulin levels.9

Thiazolidinediones (glitazones) have been associated with urothelial cancers in animal studies, and there may be a slight signal of increased risk of bladder cancer in people who take glitazones for more than two years.10

There has been some concern about GLP-1 receptor agonists and the risk of pancreatic cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis of a number of studies, however, suggests GLP-1 analogues do not increase the risk of pancreatic cancer when compared to other treatments.11 Medullary thyroid cancer has also been seen in animal studies, but no increased risk in humans has been reported as yet.12

Cancer therapies and diabetes/hyperglycaemia13

Corticosteroids are commonly used in patients with cancer to manage nausea or relieve fatigue and pain. They often cause steroid-induced hyperglycaemia or exacerbate pre-existing diabetes.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) used to treat prostate cancer is associated with risk of metabolic syndrome.

Other cancer chemotherapeutics, such as 5-flurouracil and carboplatin/paclitaxel, have also been shown to cause hyperglycaemia.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors may lead to the development of new-onset autoimmune type 1 diabetes, as well as other endocrinopathies.

Managing hyperglycaemia in people with diabetes and cancer

Managing hyperglycaemia in people with cancer can be challenging.

● Cancer therapies may lead to hyperglycaemia, which can be exacerbated by nutritional supplements and enteral feeding.

● Nausea may lead to variable oral intake, increasing risk of hypoglycaemia.

● There is no good evidence that tight glucose control improves outcomes. Management of hyperglycaemia should, therefore, be pragmatic and aimed at avoiding symptoms of hypo- or hyperglycaemia.

● Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care (JBDS-IP) guidelines suggest that all people undergoing systemic anti-cancer therapy should ideally have their HbA1c and random plasma glucose checked prior to therapy.14

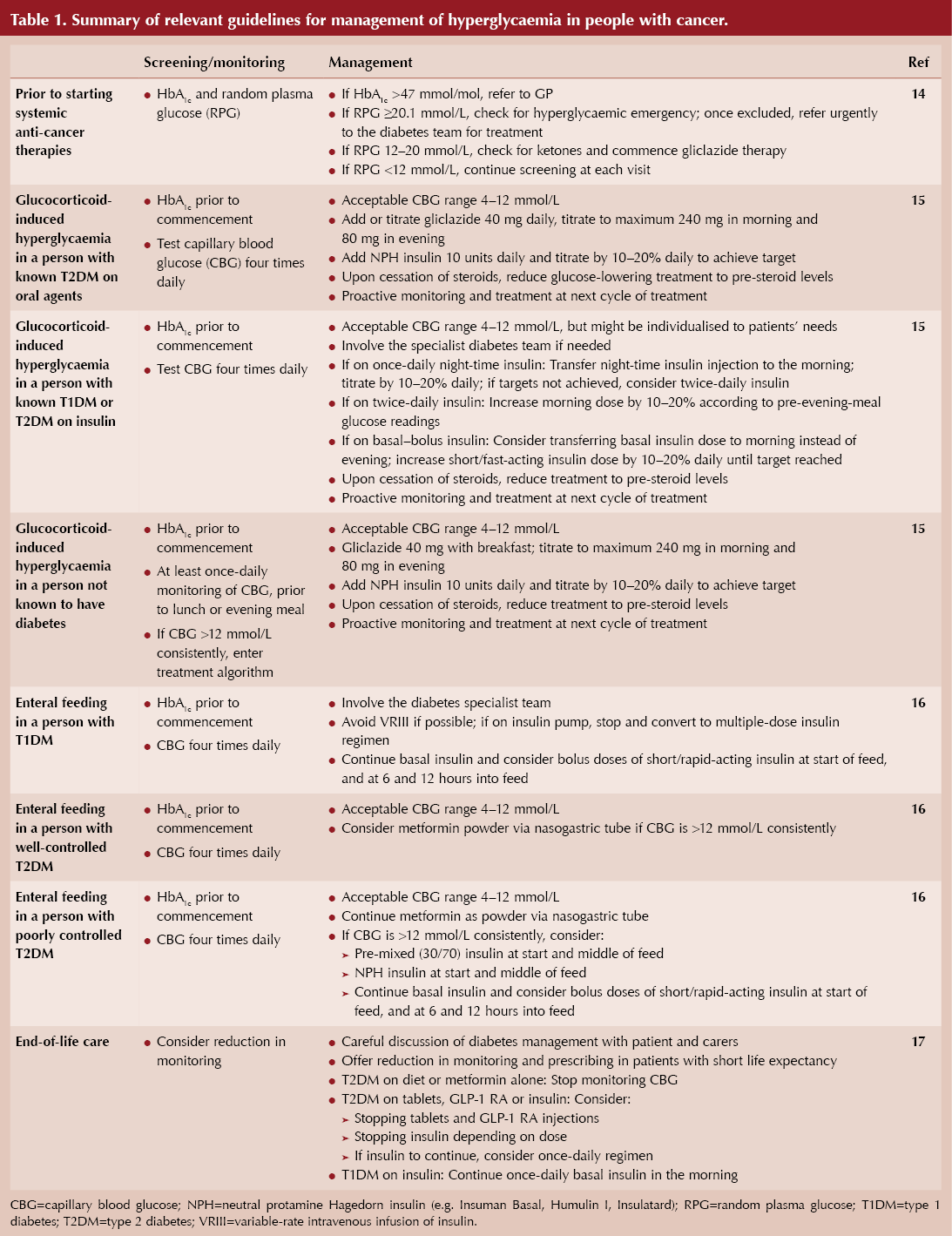

● A summary of some common clinical pathways for managing hyperglycaemia in patients with cancer is shown in Table 1.

Management of hyperglycaemia associated with glucocorticoid therapy

Glucocorticoids induce hyperglycaemia via effects on insulin receptors in liver, muscle and adipose tissue, causing insulin resistance, increased hepatic gluconeogenesis and decreased insulin secretion.

Typically, they are administered in the morning to avoid causing any sleep disturbance. The pattern of hyperglycaemia tends to be a predominantly post-prandial hyperglycaemia. In order to anticipate this, capillary blood glucose (CBG) levels should be checked regularly in people on glucocorticoids, especially in the afternoon/evening. JBDS-IP guidelines on the management of hyperglycaemia with glucocorticoids offer practical recommendations to manage this problem.15

For people at risk of steroid-induced diabetes, HbA1c should be measured prior to commencing glucocorticoids. At commencement of glucocorticoid therapy, CBG testing should be done once a day, before either lunch or the evening meal.

Treatment options include metformin, sulfonylureas or morning NPH insulin (e.g. Insulatard® or Humulin I®). A dose of 10 units should be commenced and rapidly titrated according to response. Further addition of prandial insulin may be required.

If glucocorticoids are weaned or stopped, insulin or sulfonylurea therapy should be proactively reduced to reduce risk of hypoglycaemia.

Enteral feeding

Due to the high carbohydrate content of enteral feeds, hyperglycaemia is common and achieving good glucose control is challenging.

JBDS-IP guidance recommends glucose targets of 6–10 mmol/L, in an attempt to limit the risk of hypoglycaemia.16 CBG should be checked pre-feed, every 4–6 hours during feed, and 2 hours post-feed.

Metformin powder/liquid may be considered for mild hyperglycaemia, but frequently insulin is required, and the type and dosing depends on the duration and composition of the feed. An example would be a pre-mixed (30/70) human insulin at the start and a second dose at the midpoint of the feed. It is also important to titrate insulin dose when the feed composition is changed.

End-of-life care

End-of-life care should facilitate a painless, symptom-free death, with minimal medical intervention. In discussion with the person and their family, it may be appropriate to consider cessation of non-essential medications (e.g. statins, cardiovascular risk protection drugs) to reduce tablet burden.

Glycaemic management should aim to avoid metabolic decompensation and symptomatic hyperglycaemia, but also to avoid hypoglycaemia. It may be appropriate to continue insulin once daily.17

Small but significant 12% increased risk of developing chronic cough compared to treatment with other second-line agents for type 2 diabetes.

8 Dec 2025