Primary care is most often where the diagnosis and management of long-term health conditions begins. The Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (ABUHB) provides healthcare for around 600,000 people. Nearly 40,000 people have a diagnosis of diabetes, a prevalence of 6.7%, and it is no surprise that the highest rates are in the most socially deprived areas and those with large minority ethnic populations.

Prior to 2015, the diabetes service in ABUHB was similar to that of many other health boards. Primary care practitioners and patients reported long waits for consultant diabetologist appointments, and primary care practitioners were unable to refer directly to diabetes specialist nurses (DSNs), as there were only seven of them and they all worked in secondary care. A survey of the primary care practitioners revealed they felt that they could manage patients with more complex needs, if specialist support was easily accessible. They wanted access to timely specialist diabetes advice and support, and opportunities to receive up-to-date, evidence-based diabetes education to support basic and more complex decision-making. This education should be provided locally, be free to attend and not dependent on support from the pharmaceutical industry.

Diabetes service redesign project

Initiation

In early 2015, as part of ABUHB’s wider diabetes delivery plan to improve health outcomes, a project was started to address these areas of concern. I was appointed as a Senior DSN, with a remit to manage the existing DSN team and to recruit a new team of DSNs to work in primary care. A decision was made to implement a model of care throughout ABUHB that closely resembled Portsmouth’s “Super Six” model of diabetes care (Kar, 2012; Kar et al, 2013). This model integrated primary and secondary care, allowing primary care teams to broaden their clinical responsibilities, while seven clear areas of care would remain with secondary care. Our “Super Seven” model entrusted secondary care with responsibility for caring for patients who met one of the following criteria.

2. Newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes

3. Children and adolescents

4. Pump users

5. Complex type 2 diabetes, with renal or foot pathologies

6. Pregnancy

7. Monogenic diabetes

Primary care would take responsibility for the prevention, diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes. This service redesign was supported by both the diabetes directorate and the Local Medical Committee (LMC), and was facilitated by the Diabetes Planning and Delivery Group (DPDG) and an implementation sub-group.

Role of the primary care DSN

With the reorganisation of NHS Wales in 2009, five of the former 22 unitary authorities were incorporated into the new ABUHB. I had worked within one of these unitary authorities as a primary care DSN (PCDSN) alongside all of the primary care practitioners. This ensured that specialist opinion could easily be accessed by the primary care team, such as in the management of patients requiring two or more therapies, or those whose diabetes was complex. To replicate the success of this model and to ensure equity of care, it was decided to roll it out across the whole of ABUHB.

The PCDSN team can review patients’ prescribing and test results in surgeries, people’s homes or care homes, and can access patients’ entire health profiles, including any specific health or social issues. When in the GP practice, having access to the practice patient electronic record and hospital clinical portal, including pathology and clinical letters, helps to ensure that an appreciation of concurrent prescribing, alongside that of diabetes-specific medication, is available to coproduce a clinical management plan. If a patient is seen outside of this setting, a clinical letter with the plan is written and shared with the GP practice.

The PCDSN team

A team of PCDSNs was employed and mentored by me (as senior nurse), the existing team of DSNs, consultants and an associate diabetes specialist (who is also a GP and provides educational and clinical sessions to support confidence with the making of complex decisions). Training and development began, utilising competencies developed by TREND-UK (2015). A tool, developed by the Welsh Academy of Nursing in Diabetes (WAND; https://bit.ly/2vAA83Q), was used by each PCDSN to record that each of the competencies had been met. To ensure that a focus was maintained, a target was set of one year to meet all of the competencies. This was overseen by me or one of the other established DSNs.

DSN leadership role

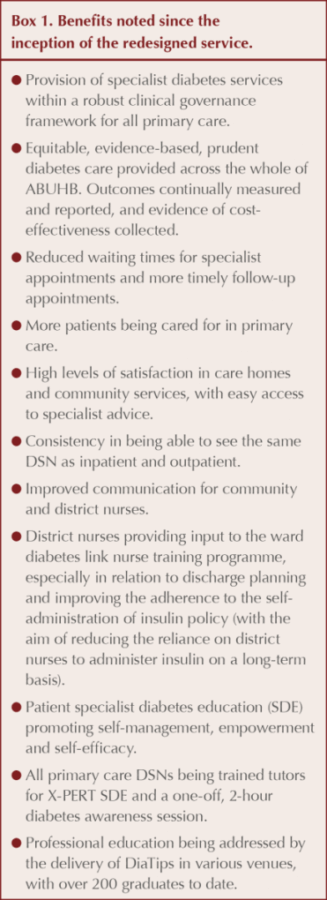

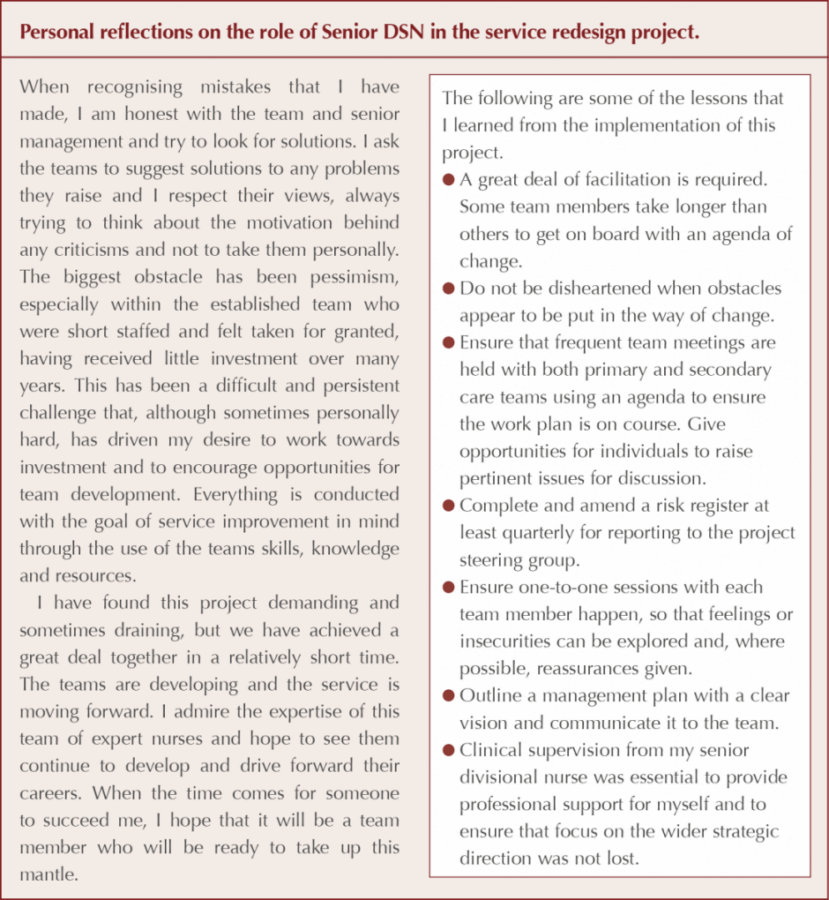

My role as Senior DSN has been to address the project’s aims and ensure that they are being met, to report on outcomes and be a visible lead within the organisation. The main aims were to: reduce reliance on secondary care diabetes services; reduce referrals to consultants; reduce the waiting lists for new and follow-up appointments; reduce admissions to hospital for hypoglycaemia; and improve access in primary care for expert specialist advice. The outcomes are monitored by the diabetes directorate, while an email advice service has been set up to provide a direct line of communication to consultants and DSNs. All of the aims have, and continue to be, met and adjustments to the brief can be made to ensure that the project continues to meet the outcome measures.

I have also been responsible for recruitment and ensuring that the newly appointed PCDSN team received adequate training and development. The appointment of a team leader for both primary and secondary diabetes care has assisted with day-to-day team management and the quick resolution of problems around the integration process. Such challenges have included confusion over which service to refer a patient with a particular problem to.

Promoting close working practices within the DSN service ensures that patients can move seamlessly between both primary and secondary care and receive evidence-based, prudent care, regardless of where it is received. Because of the history of services being set up individually by the unitary authorities, I have also worked to improve the specialist diabetes education (SDE) pathway, employing an education administrator and coordinator to centralise and standardise referrals, and redesign the education pathway to ensure equity of access.

Integrating DSN skill sets

The skills of the primary and secondary care DSN teams differ. Those in primary care centre around deteriorating control and therapy escalation, or de-escalation, with frailty or palliative care. Examples of providing healthcare professional and lay education include care staff in nursing or residential homes receiving training on the use of insulin pens and the introduction of management of glycaemia in care homes guidelines.

Skills required by DSNs in secondary care include managing the acutely unwell patient to achieve stabilisation, and developing long-term management plans for discharging inpatients and for outpatients who fall within the Super Seven criteria. They can be required to provide education and training for healthcare professionals, including junior medical staff and diabetes link nurses on the wards to improve inpatient safety.

I have attempted to develop integrated roles, with some DSNs having responsibilities in both primary and secondary care. Individuals have responsibilities to deliver the service and ensure that the two aspects of care delivery are coordinated so that the risk of patients being missed or lost to follow-up between the two services is reduced. In a pilot project, hospital inpatients, who need their diabetes to be managed differently following discharge, are seen by the same DSN when they are home. This reassures the patient and helps to prevent readmission or adverse events.

The two areas have been brought closer together but, in my experience, success depends on the individual DSN and where they feel they belong.

Professional education

Professional education was addressed by our associate specialist GP writing a course curriculum, which is jointly delivered in various locations around the health board. It is modular and free to attend, with clear learning outcomes (e.g. getting the diagnosis right and being familiar with insulin delivery devices) to equip our primary care team to diagnose and treat using the latest evidence. We have called it Diabetes Theory into Practice (DiaTips).

DiaTips is aimed at all primary care practitioners, who can dip into it according to their work schedules. It is delivered over 6 weeks in half-day sessions, and builds on existing knowledge while introducing new evidence and information in diabetes management. It has been well evaluated and has given delegates the confidence to make changes to their practice, while introducing them to the PCDSN team that provides ongoing mentorship for the course duration and beyond. Some excellent examples of new audits have resulted, including new ways to identify patients at risk of type 2 diabetes or being offered pre-pregnancy counselling.

Summary

This project was instigated to address gaps in diabetes care and improve services for people with diabetes in an area of Wales with a wide range of social and geographical variances. The project was delivered against a growing diabetes prevalence (in some areas of Gwent, the highest in Wales).

There was a reported lack of easily accessible specialist advice and support for primary care practitioners, who were relying heavily on secondary care services. This resulted in long waiting lists, medication inertia and high readmissions rates. Placing these resources in primary care, while providing the necessary support and expertise, has facilitated care to be delivered closer to home and has allowed secondary care services to focus on Super Seven patients who require specific, specialised care. It also has given primary care practitioners an educational vehicle to improve diabetes knowledge and skills, from detection and diagnosis right through the life-long pathway, giving primary care practitioners increased confidence to manage patients to a greater degree of complexity safely.

Jane Diggle discusses emotional health and diabetes distress, and offers some tips for discussing this in our consultations.

11 Nov 2025