New medicines: The present and the future

Hannah Beba, Consultant Pharmacist for Diabetes, Leeds Health and Care Partnership

● Diabetes care has moved away from a glucocentric approach to one that considers the whole person (and is “person-centric”). We need to know the people we care for – not just the drugs – and use this knowledge and understanding to develop shared and personalised management plans.

● Upstream interventions addressing prevention offer cost-effective strategies.

● We are entering an era of co-ownership of therapies with our weight management, cardiology, renal and hepatology colleagues. There are exciting new drugs for the future and opportunities to manage comorbidities together.

● The evidence base for use of CGM in people with type 2 diabetes is expanding – improvements in glycaemic control, time in range and glycaemic variability have been shown, but there remains a lack of outcomes data on severe hypoglycaemia, microvascular and macrovascular complications.

● Once-weekly insulins (insulin icodec, insulin efsitora alfa) are in phase 3 trials – results suggest comparable glucose-lowering effects but higher rates of level 1 hypoglycaemia (<3.9 mmol/L but ≥3.0 mmol/L).

● Screening to identify and treat pre-symptomatic type 1 diabetes and delay progression, including a 14-day regimen of IV teplizumab (human monoclonal antibody to CD3 on T-cells), has the potential to delay the development of stage 3 type 1 diabetes and improve beta-cell function.

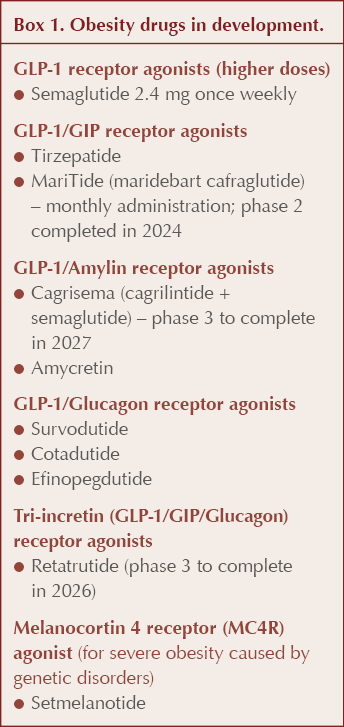

● New obesity drugs are in development, including glucagon/amylin receptor agonists and tri-incretins – see Box 1.

● Indications for established drugs are set to expand; for example, finerenone in heart failure and semaglutide in chronic kidney disease.

Debate: Triple therapy – do you treat to HbA1c or secondary outcomes?

Kashif Ali, GP and primary care lead, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde

Naresh Kanumilli, GPwSI Diabetes and Cardiology, Manchester

● A lively debate was held over which approach to type 2 diabetes management should be promoted: a holistic cardiorenal metabolic approach versus one that primarily focuses on glycaemic control?

● At the start the votes were in favour of the more holistic multifactorial approach; however, by the end, a good proportion of the audience supported a focus on glucose control:

- There is a weight of evidence to support this in reducing diabetes-related complications (see our recent Diabetes Distilled; Brown, 2024).

- In particular, the benefit of more aggressive control early on has been demonstrated.

- By definition, diabetes is a condition of hyperglycaemia.

● Ultimately, however, a consensus was reached that, whatever the approach, the person with diabetes should be at the centre of their care, as illustrated in the ADA/EASD consensus report (Buse et al, 2022).

AI prescribing: Clinician versus machine

Chris Sainsbury, Consultant Physician, NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde

● In primary care settings, 75% of family doctor contacts involve medication decisions.

● There is a higher risk of adverse events in primary care due to complex decision making involving multiple factors: patient demographics, comorbidities, other medications and so on.

● Some of this decision making could be undertaken using artificial intelligence (AI).

● How can we use AI/machine learning to assist prescribing?

- Enhancing the use of evidence already generated and extracting new information from current evidence and datasets.

● Raises many issues:

- Can a machine replicate compassionate care?

- It is based on logic and could reduce risk of human error, but at what price?

- If AI systems make an error, who is accountable?

Outstanding Contribution Award: 100 years of hypoglycaemia

Brian M Frier, Honorary Professor of Diabetes, University of Edinburgh

Professor Brain Frier was awarded the first PCDS Scotland Outstanding Contribution Award and gave a fascinating account of 100 years of hypoglycaemia research.

● Hypoglycaemia in humans was recognised as a biochemical anomaly in the early 20th century but was not considered to have any clinical significance.

● Hypoglycaemia became established as a clinical entity after the introduction of insulin to treat people with diabetes in 1922.

● Initial attempts to use pancreatic extracts in animals often produced acute toxic reactions, many of which were probably caused by profound hypoglycaemia.

● When insulin was first used, batches differed in potency and recurrent hypoglycaemia was common.

● Accurate and rapid measurement of blood glucose was very difficult and did not improve until the 1940s with the development of the autoanalyser.

● Studies in the 1970s and 1980s investigated the counter-regulatory responses that occur in hypoglycaemia and, later, the discovery that these responses became deficient in insulin-treated diabetes and exacerbated by strict glycaemic control and antecedent hypoglycaemia.

● The human brain uses 50–80% of glucose in the resting state (fasting). Function depends on continuous supply of glucose for energy needs, and profound hypoglycaemia causes coma.

● Cognitive function deteriorates at blood glucose levels <3 mmol/L.

● Attention-demanding and more complex tasks are impaired – accuracy is impaired at the expense of speed and recovery delayed after blood glucose returns to normal. Effects on everyday life are widespread and may be dangerous (for example, driving).

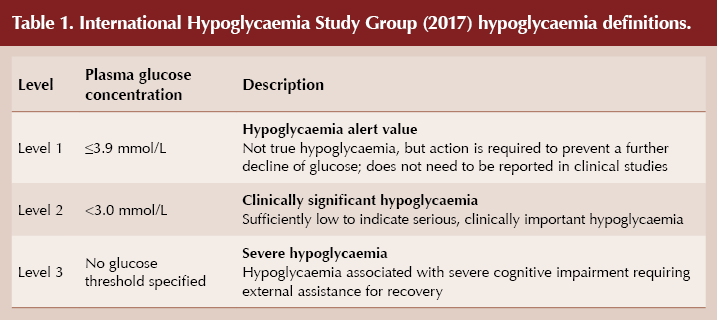

● The ADA and EASD have adopted the classifications of hypoglycaemia in Table 1, as recommended by the International Hypoglycaemia Study Group (2017).

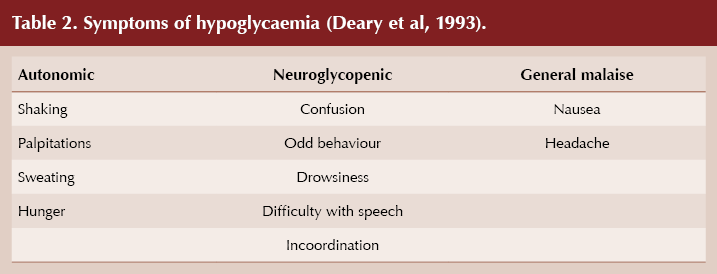

● Professor Frier provided a recap of the hypoglycaemia symptoms (Table 2), impaired hypo awareness (more common after prolonged or repeated hypoglycaemia) and the physiological and pathophysiological consequences of hypoglycaemia (effects can last up to a week and include inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and haemodynamic changes).

● He finished with reference to harm – sometimes intentional – brought about by medication-induced hypoglycaemia with a quote from Elliot Joslin: “Insulin is a potent preparation, alike for evil and for good.”

Lipids: How low should we go?

Naveed Sattar Professor of Cardiometabolic Medicine, University of Glasgow

● Cardiovascular risks are higher for people with diabetes.

● In primary prevention, for those with type 2 diabetes, risk scores should be used from age 25 years onwards. A different approach is advocated in people with type 1 diabetes, based on diabetes duration and other cardiovascular risk factors.

● Aim for LDL cholesterol <2.5 mmol/L for primary prevention and lower for secondary prevention, although European guidelines advocate an LDL <1.8 mmol/L and possibly a lower target in the future.

● Statins remain the mainstay of therapy, but ezetimibe should be considered more often, as it has a good evidence base especially in those with diabetes.

● Where there is perceived intolerance, it is worth pausing the statin (recommending a “statin holiday”), as >90% of intolerance is not genuine. Consider retrying with a lower dose to gain confidence and then increase.

● Additional lipid-lowering therapies beyond these, such as injectable PCSK9 inhibitors for secondary prevention and bempedoic acid in combination with ezetimibe, especially in those who are truly statin-intolerant.

SGLT2 inhibitors show greater cardiovascular effects in older versus young people, whilst GLP-1 RAs are more effective in younger people.

1 May 2025