Case presentation

Susan, a 39-year-old lady with a two-year history of type 2 diabetes, attended general practice reporting symptoms of thirst, increased micturition, lethargy and abdominal discomfort. She reported a weight loss of 2 kg over the last year.

Initial management of Susan’s diabetes had focused on lifestyle adjustment and treatment with metformin, which had been titrated up to a dose of 1000 mg twice daily. While this strategy initially improved glycaemic control, Susan’s HbA1c levels continued to fluctuate, running as high as 75 mmol/mol, despite careful diet, regular exercise and taking her medication as prescribed. As a result, sitagliptin (subsequently stopped because of pruritus) and more recently empagliflozin were added to Susan’s regimen. Susan, a car driver, had declined gliclazide, wishing to avoid the risk of hypoglycaemia.

Susan was up to date with her diabetes foot checks and retinal screening, and there were no diabetes complications.

Latest results (2 months previously):

- HbA1c 63 mmol/mol (7.9%).

- Total cholesterol 4.7 mmol/L.

- Non-HDL cholesterol 3.8 mmol/L.

- Hb 135 g/L.

- eGFR >90 mL/min/1.73 m2.

- Urinary ACR <3 mg/mmol.

Past medical history: Gestational diabetes.

Medication: Metformin 1000 mg twice daily; empagliflozin 25 mg once daily.

Social history: Secretary; ex-smoker; alcohol only occasionally.

Family history: Mother and first cousin with type 1 diabetes.

Examination:

- BMI 24.1 kg/m2.

- Blood pressure 125/72 mmHg.

- Cardiovascular and respiratory systems unremarkable.

- Abdomen: no significant tenderness.

Investigations:

- Dipstick urine: glucose +++, nil else.

- Fingerprick glucose: 12.3 mmol/L.

- Blood ketones: not significant.

What is your clinical assessment of the situation? What further investigations would you consider?

New-onset diabetes in a non-overweight younger adult

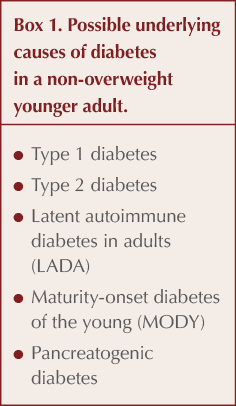

It is important to consider different underlying types of diabetes in every new diagnosis of diabetes, and the degree of uncertainty is higher in a young adult who is not overweight – see Box 1 (American Diabetes Association, 2024).

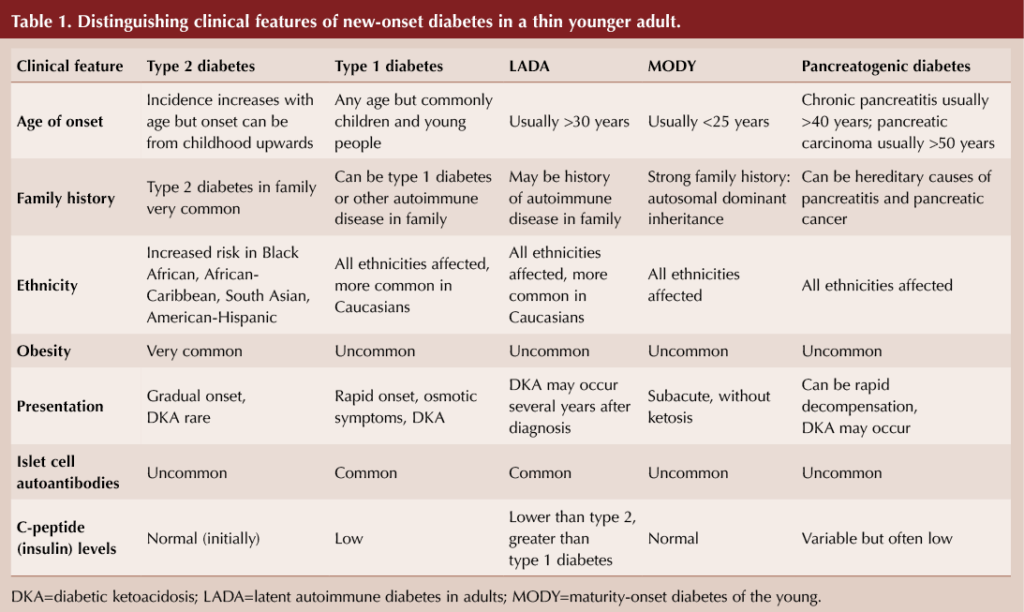

Table 1 summarises key clinical features and investigations that can help differentiate the possible types of diabetes arising in a thin younger adult (Pieralice and Pozzilli, 2018; Morris, 2020).

Case analysis

Susan had continued to have suboptimal glucose levels despite taking her medications as prescribed and engaging in a healthy lifestyle. It is possible that her urinary symptoms and weight loss were attributable to use of the SGLT2 inhibitor. However, Susan’s age, normal BMI, lack of other features of metabolic syndrome (central obesity, hypertension or dyslipidaemia) and family history of type 1 diabetes brought into question the original diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and raised the possibility of pancreatic autoimmune disease.

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) might be considered given the family history of diabetes and Susan’s normal BMI; however, this would be a late presentation (Urakami, 2019). In such a case, Susan’s previous gestational diabetes could in fact have been undetected MODY and the family history of type 1 diabetes might reflect incorrect labelling of diabetes.

Pancreatogenic diabetes cannot be excluded but this usually presents at a later age, often with a preceding history of pancreatitis (Duggan and Conlan, 2017).

It should be noted that non-overweight/obese type 2 diabetes is more common in Asian, African and Chinese ethnic groups compared with Caucasians, and lower BMI thresholds should be used in these populations when assessing risk of type 2 diabetes (Chiu et al, 2011). Type 2 diabetes can occur in people with normal or even low BMI if their fat distribution is skewed towards the visceral (i.e. abdominal) rather than subcutaneous compartment, thereby driving insulin resistance (Salvatore et al, 2023). In this context, BMI is a poor marker for judging central obesity and resulting insulin resistance (Taylor and Holman, 2015).

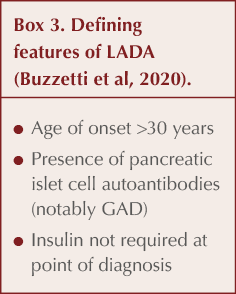

Susan’s classical symptoms of diabetes – thirst, polyuria, weight loss and fatigue – can occur in any type of diabetes. However, the duration of diabetes and absence of ketosis was not consistent with type 1 diabetes. Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), another condition associated with autoantibodies directed against pancreatic beta-cells, needs to be considered (Buzzetti et al, 2020).

Understanding LADA

LADA is a condition that clinically and biochemically lies in between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with a range of phenotypes between these two conditions. Hence, it is sometimes known as type 1.5 diabetes. Individuals with LADA are not initially insulin-dependent, and the duration before insulin is required varies from months to years (Buzzetti et al, 2020). Prevalence has been estimated as between 2% and 12% of adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes depending on the population studied (Naik and Palmer, 2003). Higher rates of LADA are seen in Northern Europeans, intermediate rates in Chinese, and lower rates in African-Americans, Hispanics and Asians (Pieralice and Pozzilli, 2018). In non-obese individuals who are initially diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, as many as 50% turn out in fact to have LADA (Naik and Palmer, 2003).

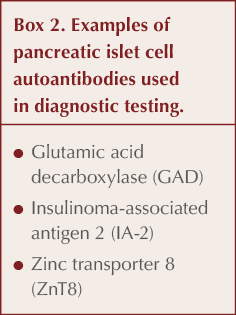

Islet cell autoantibodies that appear in LADA are similar to those in type 1 diabetes and represent an immunogenic response to proteins within pancreatic beta-cells (see Box 2). The most characteristic autoantibody and sensitive marker for LADA is glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) (Buzzetti et al, 2020).

Perhaps surprisingly, the majority of adult-onset autoimmune diabetes is likely to be LADA (i.e. not immediately requiring insulin at the point of diagnosis) rather than type 1 diabetes. While those with LADA tend to be younger and leaner than people with type 2 diabetes, the phenotypic distinction between LADA and type 2 diabetes is not categorical. It is the presence of autoantibodies, notably GAD (around 90% of autoantibody-positive individuals have GAD autoantibodies), that allows a definitive diagnosis (Hawa et al, 2013).

Individuals with LADA expressing high levels of GAD autoantibodies are likely to experience a more rapid progression to requiring insulin (Pieralice and Pozzilli, 2018). In general, multiple autoantibodies increase the rapidity of progression to insulin dependence.

The defining points of LADA are listed in Box 3 (Buzzetti et al, 2020). Interestingly, the American Diabetes Association (2024) does not identify LADA as a specific type of diabetes but rather as a form of type 1 diabetes (involving autoimmune beta-cell destruction) that evolves more slowly.

Why is it important to recognise LADA?

The ultimate concern for people with LADA is that, over time, they become at risk of decompensation to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening emergency, when insulin production is no longer sufficient. Therefore, in patients developing osmotic symptoms and/or a sudden rise in HbA1c, it is vital that DKA is excluded through checking random blood glucose and ketone levels. This problem must be anticipated and the individual warned how to recognise possible DKA and what action to take. Pre-emptive initiation of insulin may be chosen to avert this crisis from arising.

Maintained beta-cell function is associated with reduced incidence of retinopathy and nephropathy in people with type 1 diabetes (Steffes et al, 2003). By extension, identification of LADA is important because it allows selection of medication that preserves beta-cell activity and endogenous insulin production (Buzzetti et al, 2020).

When to suspect LADA

Consider the possibility of LADA in younger people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (notably in the age range of 30–50 years), particularly if they are not overweight or obese (Buzzetti et al, 2020). That said, LADA can occur in older people and a raised BMI does not exclude the diagnosis. A personal or family history of autoimmune disease increases the likelihood that the diagnosis may, in fact, turn out to be LADA.

The absence of hypertension and dyslipidaemia may also shift the focus from type 2 diabetes towards LADA. People with LADA are less likely than those with type 2 diabetes, but more likely than those with type 1 diabetes, to have features of metabolic syndrome. A poor response to medications for type 2 diabetes (as exemplified by Susan’s case) may be indicative of insulin deficiency, consistent with LADA.

Investigations for LADA

Whilst clinical features may indicate the possibility of LADA, diagnosis will ultimately depend on measuring pancreatic islet cell autoantibodies. GAD autoantibodies should be the primary biochemical marker used to aid diagnosis of LADA (Hawa et al, 2013). A reasonable strategy for identifying LADA is to target autoantibody testing in those people with diabetes who have clinical features suggesting the condition: age 30–50 years, BMI <25 kg/m2, and/or personal or family history of autoimmune disease (Davies, 2021).

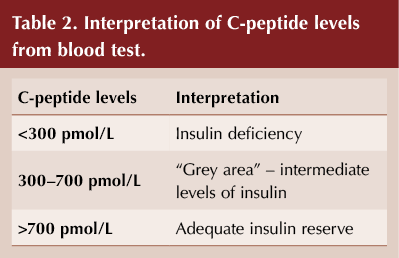

Levels of C-peptide can also be helpful in distinguishing LADA from type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and to direct management (see Table 2). C-peptide is a molecule secreted in a 1:1 equimolar ratio with insulin (it links the alpha and beta chains of insulin into the single polypeptide chain of proinsulin). It is easier to measure than insulin but accurately reflects levels of insulin.

At the point of diagnosis of diabetes, C-peptide levels will likely be normal in people with type 2 diabetes (or even raised, due to insulin hypersecretion to overcome insulin resistance), low or undetectable in people with type 1 diabetes, and reduced (but not as low as in type 1 diabetes) in those with LADA (Bell and Ovalle, 2004; Pipi et al, 2014; Hernandez et al, 2015). The progression of LADA may be determined by falling C-peptide levels.

Familiarity and accessibility of these tests may be restricted in the context of primary care, and thus clinical suspicion of LADA usually requires referral to the specialist diabetes team.

Management of LADA

The evidence base for treating LADA is weak. Pragmatically, the pathways established for type 1 and type 2 diabetes are extrapolated to those with LADA. In practice, people with LADA are likely to be managed in secondary care.

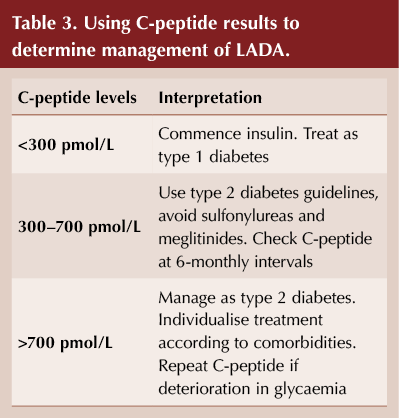

The key question in terms of pharmacological management of LADA is when to commence insulin. Individuals who are achieving appropriate glycaemic levels using medication for type 2 diabetes may continue with these treatments, especially if they have features of metabolic syndrome and lower levels of GAD autoantibodies. In contrast, if glycaemic control is suboptimal on type 2 diabetes medications and the phenotype is more consistent with type 1 diabetes, or if GAD levels are high, then a switch to insulin therapy is appropriate.

C-peptide levels have been recommended by an expert consensus panel as a guide to managing people with LADA and, in particular, when insulin should be started (Table 3; Buzzetti et al, 2020).

Management with non-insulin therapies

Management of LADA without insulin should, in general, follow the NICE (2022a) NG28 guideline for type 2 diabetes. Thus, metformin would be the first-line treatment for glycaemic control. The selection of further agents (DPP-4 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, pioglitazone, SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists) will depend on individual characteristics, including comorbidities (notably cardiovascular disease, heart failure and chronic kidney disease), the need for weight loss and the need to avoid hypoglycaemia.

Sulfonylureas and meglitinides (such as repaglinide) may best be avoided in LADA because their action in stimulating beta-cell activity may exacerbate the autoimmune process and accelerate beta-cell loss, possibly aggravating microvascular complications (Pieralice and Pozzilli, 2018). Given the risk of decompensation to DKA with LADA, it may also be prudent to avoid SGLT2 inhibitors in the situation of reduced insulin reserve, as this class of medication increases risk of DKA (MHRA, 2015; MHRA, 2016; Wilding et al, 2018).

Individuals with LADA who are not using insulin should check their blood glucose levels several times a week, at varying times of the day. If these rise suddenly and remain elevated, this may indicate falling insulin reserve and impending decompensation to DKA. Under such circumstances, the key test would be for blood ketones, checked by the person or a healthcare professional, and a positive result would require immediate referral to secondary care for insulin initiation.

Management with insulin

The argument can be made that introduction of insulin should be considered in all people with LADA because this would avert the future risk of serious illness from decompensation to DKA. People with LADA need to be involved in this discussion so that they can make an informed choice.

Where insulin is deemed necessary, individual circumstances and biochemistry will direct the choice of regimen. A basal insulin commenced alongside oral antidiabetes therapies may be the simplest first step. Ultimately, the best option for glycaemic control in LADA will be a basal–bolus insulin regimen, as employed to manage type 1 diabetes (NICE, 2022b). When insulin is started, a full education programme will be necessary, as with type 1 diabetes, and regular glucose monitoring will need to be undertaken.

People with LADA are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Where appropriate, advice on dietary adjustment, exercise and weight loss should be provided. Hypertension and dyslipidaemia should be managed in line with guidelines for type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and smoking cessation encouraged where necessary (NICE, 2022a; NICE 2022b).

Case outcome

Recognising the possibility of LADA, the GP Registrar arranged a blood test to look for beta-cell autoantibodies. A positive result would strongly support the diagnosis of LADA, whilst a negative result would be expected with type 2 diabetes, MODY and pancreatogenic diabetes.

Susan’s GAD antibody testing yielded a positive result of >2000 units/mL. This result clinched the diagnosis of LADA. Susan was referred urgently to the secondary care endocrinology clinic, where she was commenced on a basal–bolus insulin regimen of once-daily Abasaglar (biosimilar insulin glargine) plus mealtime Humalog (insulin lispro), along with appropriate education. Both metformin and empagliflozin were stopped.

C-peptide levels subsequently returned as borderline low, consistent with a diagnosis of LADA.

Article learning points

● LADA is a slowly progressing form of autoimmune diabetes with antibodies directed against the pancreatic beta-cells. The most characteristic autoantibody is GAD.

● LADA typically presents in people over the age of 30 years and has a clinical and biochemical picture intermediate between type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

● Because there is no immediate requirement for insulin, LADA is often initially diagnosed as type 2 diabetes.

● Suspect LADA in the younger, non-overweight person diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, especially if there is a personal or family history of autoimmune conditions. Consider GAD antibody screening in people with these characteristics.

● LADA can be managed with medications for type 2 diabetes, although sulfonylureas are best avoided and SGLT2 inhibitors should be used cautiously.

● Individuals with LADA are at risk of decompensation to DKA. It is important, therefore, that they monitor symptoms and glucose levels, and where necessary test for ketones and seek medical advice.

● C-peptide levels are a measure of insulin reserve. With adequate levels, type 2 diabetes treatment pathways can be followed, whereas low levels signal the need for insulin.

● People with LADA should have cardiovascular risk factors addressed in line with NICE guidelines for type 1 and type 2 diabetes management.

Introducing the PCDO Society’s new podcast. In episode 1, we cover the updated NICE NG28 guideline on type 2 diabetes management.

24 Feb 2026