The International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes and the NICE guidelines recommend that young people and their families receive psychological support as part of their diabetes care (Delamater et al, 2014; NICE, 2015). The introduction of the paediatric diabetes Best Practice Tariff (Department of Health, 2012) in England has led to greater integration of clinical psychologists within paediatric diabetes multidisciplinary teams, and increased access to psychological assessment and intervention for young people and families as part of their diabetes care (Alsaffar and Satish, 2015; Binney and Roswess-Bruce, 2015).

While much research has focused on the effectiveness of various types of therapy in improving physical and psychological well-being in young people with T1D (e.g. Viner et al, 2003; Ellis et al, 2005; Winkley et al, 2006; Channon et al, 2007), little research has examined young people’s perceptions of how psychological therapy may help bring about change in their physical and mental health. Understanding what young people want and need from psychological support in their diabetes service is essential for informing practice and optimising engagement in order to achieve meaningful improvement in health outcomes (Levitt et al, 2006; Lavis and Hewson, 2011).

This study aimed to explore the experiences of adolescents with T1D who had received psychological therapy within a paediatric diabetes service, and investigate the factors they perceived as important in facilitating change.

Methodology

In this cross-sectional and qualitative study, adolescents with T1D completed semi-structured interviews with the primary researcher following the completion of psychological therapy. The primary researcher was independent of the therapy delivered.

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate if they had T1D, were between 11 and 18 years old, had received at least six sessions of psychological therapy, had completed their therapy within the past 6 months, and if there were no language or learning problems that would prevent either the parent or adolescent giving informed consent, assent or taking part in the interview.

Demographic data for the eight young people who participated in the study are summarised in Table 1. On average, participants had attended the diabetes clinic for over 9 years (mean: 111 months; SD: 54.97 months), and reported an average of 9.63 sessions with psychology (SD: 3.58) over a period of 10.94 months (SD: 5.93).

All had received routine psychological therapy from a clinical psychologist or trainee clinical psychologist as part of their regular diabetes care. This therapy was typically an integration of cognitive-behavioural and systemic approaches. The focus of psychology input, as reported by families, included:

- Developing confidence and independence with diabetes management

- Improving treatment adherence

- Reducing negative thinking or emotions about diabetes

- Difficulties with restricted diet

- Managing anxiety or low mood.

Measures

This study used the Change Interview (Elliott et al, 2001), a semi-structured interview focusing on changes noticed during therapy, how important or significant they were believed to be, what the changes were attributed to, and what was helpful or hindering in therapy. This interview protocol has been widely used in psychological change process research (Elliott, 2010) and has been used to analyse young people’s experience of counselling (Lynass et al, 2011). Some minor adaptations were made to the wording to ensure that the questions were meaningful to young people. All participants also completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

Procedure

Prior to recruitment, ethical approval was obtained from the University of East Anglia Faculty of Medicine and Health, and registered as a service evaluation with the Patient Risk and Safety Department at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Informed consent (from parents) and assent (from young people) was gained prior to interviews commencing.

Interviews were held at the diabetes clinic that the young people usually attended, at a time convenient to the family. Young people were interviewed on their own to give them space to express their views. Interviews were audio recorded and took 20–30 minutes per person.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used, as it is exploratory and does not aim to fit patient experiences with existing theory (Lynass et al, 2011), although the researcher used a broadly top-down approach (Boyatzis, 1998) to identify themes in relation to the research question. The primary researcher took an essentialist standpoint during analysis, with the goal of reporting experiences and meanings as seen from the service-user perspective.

Following the steps of Braun and Clarke (2006), all interviews were transcribed and coded, and corresponding themes were identified by the first researcher. To maintain rigour, the primary researcher kept a reflexive journal throughout in order to critically examine personal influence or bias. A second researcher reviewed the data to ensure the themes represented meaningful patterns of the adolescent experience.

Results

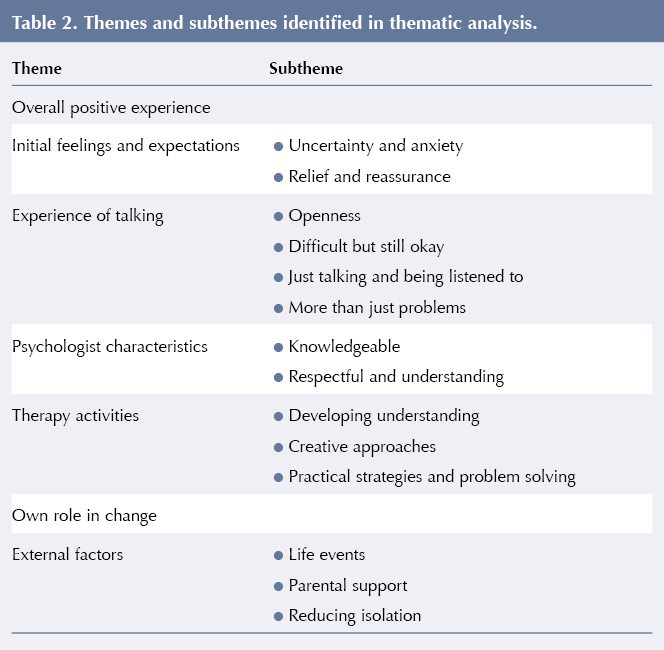

Seven themes and several subthemes were identified around the experience and helpful aspects of psychological therapy (Table 2). These are described below.

Theme 1: Overall positive experience

All participants reported that they had found psychological therapy to be a positive experience and that things had changed for the better. When asked about negative or unhelpful aspects of therapy, very few individuals offered examples. These situations were generally defined as ‘difficult, but still helpful’ (see Theme 3).

Theme 2: Initial feelings and expectations

All participants reflected on initial expectations. Two subthemes were identified. The first represented feelings of uncertainty and anxiety about what to expect from seeing a psychologist:

‘I think sometimes people are a bit worried about going at first, because they’re not sure of what it’s going to be like and… if it’s going to be helpful.’

Despite initial concerns, participants also reported feeling relieved and reassured (subtheme 2) after attending their initial appointments:

‘I at least now know what’s happening.’

They felt that the process was not so scary, and that they were receiving help.

Theme 3: Experience of talking

A third theme was identified around the process and experience of talking to a psychologist. There were four subthemes here (see Table 2).

Participants described feeling that they could talk openly and comfortably. Some identified that the confidentiality of appointments allowed them to feel safe to talk.

Some participants described that the process or content had felt difficult to deal with at times during therapy, but that they had still found therapy helpful and wanted to engage with it. Many participants reported that just talking and starting some of the difficult conversations was helpful in itself:

‘I think the big one was just, almost, talking about it… because, as they put it, the further you try to push it to the back of your mind, it just always sort of… takes control… so it was just almost talking about it which was the biggest help.’

Others reflected that the conversation had not focused solely on diabetes or other difficulties, and liked that there had been problem-free talk:

‘It wasn’t always worry. It was just general things sometimes, which was quite nice, because it put sort of a less serious side on it.’

Theme 4: Psychologist characteristics

Participants commented on the qualities of their psychologist that they believed helped to bring about changes during therapy. These qualities broadly came under two subthemes. Some participants perceived psychologists as having knowledge that they or their families did not possess, which could help them bring about change:

‘[Mum] wanted me to be more confident and things like that but she didn’t know how, so it was quite hard to do, but then when [the psychologist] explained, how the different ways you could do it and like, to choose one, then it made it easier.’

Other participants commented on the manner in which the psychologist made them feel respected and understood:

‘I did enjoy it […] There’s no patronising. Like [the psychologist] understood just everything.’

Theme 5: Therapy activities

Most participants identified specific tasks that they felt increased their understanding and helped them develop strategies to manage difficulties. Three subthemes were identified (Table 2). Participants described processes such as psychological formulation and guided discovery as helpful in the development of understanding:

‘I told her all the things I was having problems with and she managed to like, draw a cycle out, and sort of made me understand how everything’s linked and how to eventually, when I do break out of the cycle, how to somehow stay out of it.’

A number of participants also mentioned approaches such as using imagery and metaphors, drawing, or externalising the problem as being helpful aspects of therapy. Others identified that therapy had helped them to devise and practice strategies for managing problems.

Theme 6: Own role in change

A number of participants highlighted that as well as psychology, personal motivation and practice outside of therapy contributed to change:

‘You have to actually willingly want to do it, the helpful thing is they’re [the psychologists] there to help.’

‘[Homework] was quite good, ’cause then that’s not like, leaving it here; it’s like, taking it home as well, so it’s like, not pointless, basically.’

Theme 7: External factors

Another theme suggested that factors outside of individual psychological therapy had a role in helping to motivate or generate changes. There were three subthemes. These included ‘life events’ (such as starting secondary school, taking GCSEs or commencing work) and ‘parental support’ with changes they hoped to make.

Importantly, participants reported that they often felt alone with their diagnosis. Several young people highlighted the benefits of ‘reducing isolation’ by talking with other people who have diabetes:

‘I think it makes it easier ’cause […] at first, you feel like you’re the only one, ’cause you don’t really know anyone else with it, ’cause there’s no one at my school with diabetes, it’s only me, so you feel a bit alone, but then when you meet people then you understand that people are going through the same thing as you are.’

Discussion

The findings from the semi-structured interviews illustrate that the adolescents in this study perceived psychological therapy as being positive and helpful in bringing about desired changes in their diabetes management and personal well-being. Young people valued being able to talk openly, being listened to, and being able to discuss difficult topics within therapy. Several participants commented on talking about things other than difficulties, which suggests the importance of ‘problem-free talk’ (O’Hanlon and Weiner-Davis, 2003) in allowing psychologists to learn about the person outside of the problem (Christie, 2008).

Consistent with Elliott and James (1989), participants identified therapist- and task-specific aspects as being helpful in bringing about change. Young people reported that psychologists could offer unique knowledge, but also highlighted respect and understanding for their own perspectives as being important. This suggests that adolescents valued engaging in collaborative psychological work, and is consistent with findings in adult populations where client involvement and empowerment have been reported as helpful aspects within therapy (Timulak, 2007).

In line with Timulak’s (2007) findings in adults, young people identified ‘developing understanding’ and ‘learning practical strategies’ as helpful in bringing about change. Additionally, adolescents with T1D recognised the helpfulness of more creative approaches, such as imagery, drawing or externalising the problem. This highlights an area more uniquely important in therapeutic work with young people, and is consistent with some treatment protocols for diabetes-related distress (e.g. Christie, 2008).

Adolescents also believed that just attending psychology sessions was not enough to make change occur and described personal willingness to change, the support of parents, and other life events as being important factors in effecting change. This is consistent with research suggesting that around 40% of therapeutic change may be due to extra-therapeutic factors (Lambert, 1992). Young people felt psychology went hand-in-hand with their life experiences and that both were important for change to occur.

Additionally, a sub-theme was identified around reducing feelings of isolation, which are often experienced by young people with diabetes (Christie and Martin, 2012). This suggests that some young people felt there was a type of understanding that could not be provided by parents or psychologists, but could only be received from other young people with diabetes who could personally relate to their experiences.

Implications for clinical practice

While giving a generally positive message about the perceived helpfulness of psychological therapy as part of diabetes care, this study highlights that worries or misconceptions about psychology may prevent some adolescents from engaging with services. Adolescents may therefore benefit from education or reassurance about what is involved in psychological services.

Young people with diabetes face a daily challenge managing HbA1c and controlling their blood sugar levels. Therapies that embody an empowering, creative and collaborative approach, such as solution-focused or narrative approaches, might be particularly acceptable and useful for young people with diabetes. Findings also suggest that psychologists may have an important role in facilitating groups or providing other opportunities in which young people with diabetes can connect with each other in order to feel understood and less isolated.

Limitations and future research directions

This study surveyed a small number of self-selected adolescents at one clinic, so the findings cannot be generalised widely. The participants had all been willing to engage in at least six sessions of psychological therapy, which may have led to more positive overall impressions. At the time of the study, the primary researcher was a trainee clinical psychologist, which may have introduced bias, either on the side of the researcher, or from young people aware of the researcher’s job role. Future research could survey a larger, more diverse group of young people with T1D from a range of clinic sites, with an interviewer from a different professional background.

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to ask adolescents with T1D what they think helps bring about change when receiving routine psychological therapy at a specialist diabetes outpatient clinic. The findings suggest that some of the helpful therapeutic factors identified in research with adults may be applicable to young people with T1D attending psychology appointments. This study also indicates that there may be some additional factors to consider in this population, in particular the inclusion of problem-free talk, using creative approaches to engage young people, and work around reducing feelings of isolation.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022