Friday 9 September 2016 is a day I will never forget – both as a parent and a professional – as it ended with my then 14-year-old son Mackenzie in a high dependency unit (HDU) with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. As a qualified children’s nurse and health visitor, I knew a little bit about type 1 diabetes and its symptoms, but had not had much experience with it. I do not recall it being included in my education, despite it being one of the most common conditions affecting children and young people (Naranjo and Hood, 2013).

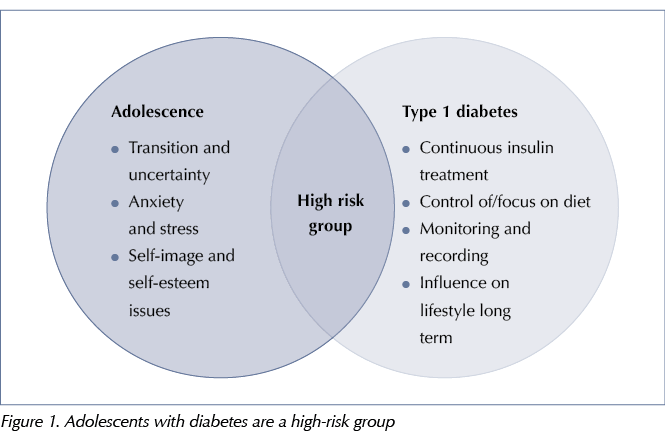

Diabetes UK’s (2017) 4 Ts campaign is raising awareness of the condition and I would like to see its posters in all schools, health centres and, perhaps, sports and youth clubs, as this may improve diagnosis and reduce the number of acute hospital admissions (Figure 1).

Symptoms

Over the summer holidays Mackenzie had lost weight, was sleeping and drinking more, and had terrible mood swings. He was also using the toilet very frequently, including at night, but I put this down to the fact that he was drinking so much. All of these symptoms were easily explained in other ways: he was a teenager, he was growing, he was out on his bike and active all day, and it was warm.

The severity of these symptoms hit me on the first week back at school in early September as the uniform I had bought only weeks before now hung off him. I weighed Mackenzie and realised he had lost around 3 stone and his face was very drawn. I also observed him drinking pint after pint of water but still complaining that he could not swallow food because his throat was so dry. I later found out that his teachers had been concerned about the changes in him and thought he may have had an eating disorder. They may have been able to recognise the symptoms of diabetes if they had been informed about it and I feel that more education for teachers and schools would therefore be beneficial.

On Thursday Mackenzie’s mouth was visibly dry and cracked. His bedroom smelled sweet due to ketones, as he was in early DKA, but I was not unduly concerned as it was not the typical “pear drop” smell I associated with diabetes. I feel that describing the smell as sweet would be more accurate.

I made a GP appointment for Friday evening, as that was the earliest available slot. I explained my concerns and Mackenzie’s symptoms. The GP enquired whether there was any history of type 1 diabetes in the family – there was not – but did not offer a finger-prick blood glucose (BG) test. Instead the GP arranged for Mackenzie to have blood tests in the clinic the following week.

Once home I was furious with myself for not challenging the GP. As a nurse, health visitor and lecturer, I felt that I should have been confident enough to do so. Had it been in the work place I feel I would have, but it is difficult when there is personal or emotional involvement. I now know that any child presenting with symptoms of type 1 diabetes should be immediately referred to a specialist team for appropriate assessment (NICE, 2015). I have since raised this matter with the practice manager and a new policy has been implemented whereby any child presenting with symptoms will have a finger-prick test and be referred appropriately.

I managed to source a BG meter from a friend to carry out a BG check. The meter did not give a numerical reading – it simply indicated “HI”, which on that particular machine meant that Mackenzie’s BG was above 30 mmol/L. We went straight to A&E.

Diagnosis and admission

Several medics assessed Mackenzie and explained it was probably type 1 diabetes as his ketones were >4 mmol/L and he was acidotic. They then informed me that Mackenzie was lucky to be standing, and had I waited until Monday he would likely have been admitted via ambulance and been unconscious. Within minutes Mackenzie was on fluid and insulin drips (although intravenous access was struggle due to the dehydration). I was in such a daze I did not realise for some time that he was in a high-dependency unit (HDU) bed.

Overnight he was stabilised and the next day we were shown how to use the equipment and administer insulin. Unfortunately there was no diabetes specialist nurse (DSN) available, as it was the weekend, and some of the nurses were unsure how to use the glucometer and insulin pens provided. I think that all children’s ward staff should receive regular training and updates on this, or that DSNs should be on call for newly diagnosed patients and their families.

Mackenzie was transferred from the HDU to a side room, which was good as it was a on children’s ward. The staff members were mindful that he was a teenager and this made a positive difference to our experience.

Over the next few days we learned basic diabetes management. Although I had looked after children with diabetes in the past, I had no idea of the complexities involved. Because of his age, a lot of the education was directed towards Mackenzie, but I was very observant too and my lack of knowledge shocked me. The education was good and the nurses were great, but I found the way it was delivered very matter-of-fact and felt the nurses could have displayed more empathy and compassion. I was grieving, as diabetes was going to impact everything Mackenzie did for the rest of his life. At one point I was so tired and consumed by guilt, anger and an overwhelming feeling of sadness that I locked myself in the bathroom and just cried.

The role of the DSN and diabetes team

After being discharged we were assigned a DSN, Rachael. Her initial home visit was incredibly useful. She spent an extended period of time (way past her working hours, I suspect) advising us and answering our many questions. I explained our struggle with fixed insulin doses and that we had to alter them to fit with what Mackenzie was eating to prevent hypoglycaemia. Rachael explained the basics about counting carbohydrates and adjusting insulin doses, which made much more sense to us. NICE guidance (2016) states that families should be taught how to count carbohydrates as part of the daily management of type 1 diabetes. Rachael revisited and developed this topic at each contact to ensure a sound understanding.

During her first visit, Rachael also introduced the idea of an insulin pump as an alternative to injections. She disclosed that she had type 1 diabetes and used a pump, which was incredibly reassuring, as she had personal experience and was able to provide advice that was professional but realistic, with achievable goals. Although our other DSN, Leeanne, was also brilliant, in those early days Rachael was a unique and invaluable source of understanding and support for both Mackenzie and me. I think that in the absence of a DSN with type 1 diabetes, it would be beneficial for teams to have access to a bank of peer-support workers – whether other parents of children with type 1 diabetes or young people with the condition – who have been through the process.

The combination of home visits, email contact and text messages we have received works very well. Along with the regular telephone, letter and clinic contact, we have never felt alone or unsupported despite the burden of type 1 diabetes. This reflects the recommended care package proposed by NICE (2016), although others have complained of a lack of support within their area. Equity needs to be addressed to ensure all children and young people can achieve the best outcomes.

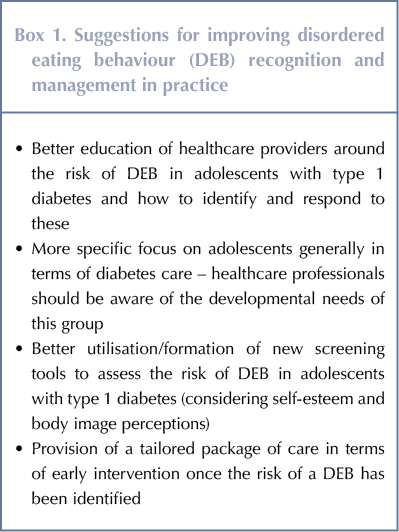

Paediatric diabetes teams need to focus on the adolescent years, as this age group is unique and vulnerable. Adolescents require a tailored package of care and need to be involved in developing this. Information needs to be “drip fed” in my experience, as information overload is counteractive. Teenagers need to be involved in setting achievable goals and should be given encouragement and praise without being patronised. Targets need to be aimed for, but developing good future practices bit by bit is more beneficial than taking an authoritarian and dictatorial approach, which, in my experience, leads to non-compliance. The focus should be on what can be improved, what is being done well and whether anything needs to be tweaked. The family should be involved in home and clinic appointments and educated accordingly, but care should be targeted towards the young person, as they need to feel supported but also develop autonomy.

Daily life and challenges

Diabetes is part of everyday life for us as a family now and we have tried to accept it as a new “norm”. My husband and I both work full time and, as well as Mackenzie, have a 10-year-old son to look after, but just getting through a day with diabetes sometimes feels like a full-time job. There has been a lot of stress and family conflict. Weekends and school holidays can be challenging, as there are late nights and little time structure.

Most of the time we feel like we are doing well. Mackenzie has not been back in hospital since his initial diagnosis. We try not to let diabetes take over or dictate our behaviour, but, in all honesty, it does. Our once almost independent young man with a lot of freedom suddenly became dependent again. It was particularly difficult in the early days, when we were testing Mackenzie’s BG through the night. There is so much involved in caring for a young person with diabetes: testing BG (at least) four times a day, weighing food to work out the carbohydrates, adapting insulin/carbohydrate ratios, treating high/low blood sugars, dealing with mood swings (when most of the time we do not know if it is diabetes or just hormones), checking supplies, ordering and collecting prescriptions, attending clinics, dietetics, podiatry and retinal screening appointments. The list feels endless.

Before the diagnosis I had “normal” anxieties about parenting a teen; these now seem trivial as I worry whether he will wake up in the morning, whether he will collapse when out and about, and what the future holds for him. I worry about my ability to safeguard him when he starts going out drinking with his friends in a couple of years. Unfortunately my concerns are rarely met with gratitude and are seen as “nagging”. Adolescents are not capable of the same level of reasoning or cognitive thinking as an adult. They do not have the capacity to appreciate cause and effect in the same way and are incapable of seeing themselves in the future. His lack of communication with me when he is out causes me great anxiety, but from his perspective it is not a problem because by that point he is home and is “fine”. I feel that sometimes being a nurse I only think about the things that can go wrong. I am trying to educate Mackenzie so as an adult he will feel empowered to manage the condition well himself.

I appreciate the fact that Mackenzie never refuses his insulin, always attends appointments willingly and does finger-prick tests regularly (when he does not, it is down to forgetfulness rather than non-compliance). As a member of an online support forum for parents of children with type 1 diabetes, I see other parents complaining regularly about their children refusing to test their BG, totally disregarding their condition and skipping their insulin.

Mackenzie’s diet at home is good, but when he is out with friends he eats fast food and crisps like the rest of them. The only thing we tend to completely avoid is full-sugar soft drinks, which is not an issue as they are not something we tended to drink in the past. I imagine the fact we have not really had to change our eating habits as a family has made the normalisation of living with diabetes easier; in families where diet is poor, this would undoubtedly be a challenge.

Most of the time at school Mackenzie manages well, as there is a routine. The diabetes (mostly) blends in to the background. I do feel, however, that schools need more training around the complexity and importance of managing diabetes, as I am not sure they really understand it or the related dangers.

Mackenzie is using a wireless pump now and this seems to be working for him. The fact that it is waterproof and carbohydrates are entered onto a handheld Bluetooth device makes it easy to use and modern. It allows Mackenzie to eat more freely and bolus often without the need for injections, and takes away the restrictions of a wired pump. We are lucky to have access to funding for this within our local trust: families are often required to join waiting lists or self-fund the pump – a burden some families cannot take on. The pump is relatively big and bulky compared to some of the wired pumps, although for a large teenage boy this is no problem and he wears it on his arm without any issues. This situation may be different for a smaller child or a self-conscious adolescent who has concerns or insecurities around body image.

Most recently, Mackenzie has begun using the FreeStyle Libre sensor. The resulting reduction in finger pricking has made life much easier. We feel very lucky that, after a period of self-funding, it is now available to us on prescription.

Looking ahead

As a family we are well educated, secure, have no other complexities and I am health professional. Despite all of this, we have found this situation very difficult at times. I often think about complex families that I have worked with who presented with a multitude of additional needs and struggled with even the most basic of parenting skills. It is at these times that I feel the work we are putting in will give Mackenzie an advantage going into adulthood.

Sadly, we have lost Rachael’s support as she moved to another geographic area, but Leeanne and Claire are great DSNs and the communication and support we receive has remained consistent. I thank them for this, as their help and support makes fighting this lifelong battle with type 1 diabetes so much easier.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022