In September 2016 I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. I was aged 14 years. Not long before this, my mum (a health visitor) had started to notice that I had common symptoms, such as drinking large amounts of water, constantly using the toilet and being very tired. My bedroom also had an odd sweet smell each morning when I woke up, to the point where she thought I’d been drinking alcohol. Just before diagnosis we realised that I had lost around 3 stone in weight, in 6 weeks, without dieting.

Diagnosis

My mum was very concerned and suspected diabetes, so she took me to the doctor one Friday after school. We explained the symptoms: exhaustion, extreme thirst, weight loss and excessive toilet use. He asked about diabetes in the family (there isn’t any) and ordered bloods. It was Friday, so I would have to wait until Wednesday for the blood clinic. My mum was not very happy with this, but we left and went home. I had football training that evening but I noticed something strange; I was struggling to even lift my legs – a kind of extreme fatigue I had never experienced before. I could barely move, let alone run. I even struggled at this point to stand. I sat on the side of the pitch and called Grandad to come and pick me up as I knew I wouldn’t be able to walk home as I usually did.

“I noticed something strange; I was struggling even to lift my legs – a kind of extreme fatigue I had never experienced before. I could barely move, let alone run.”

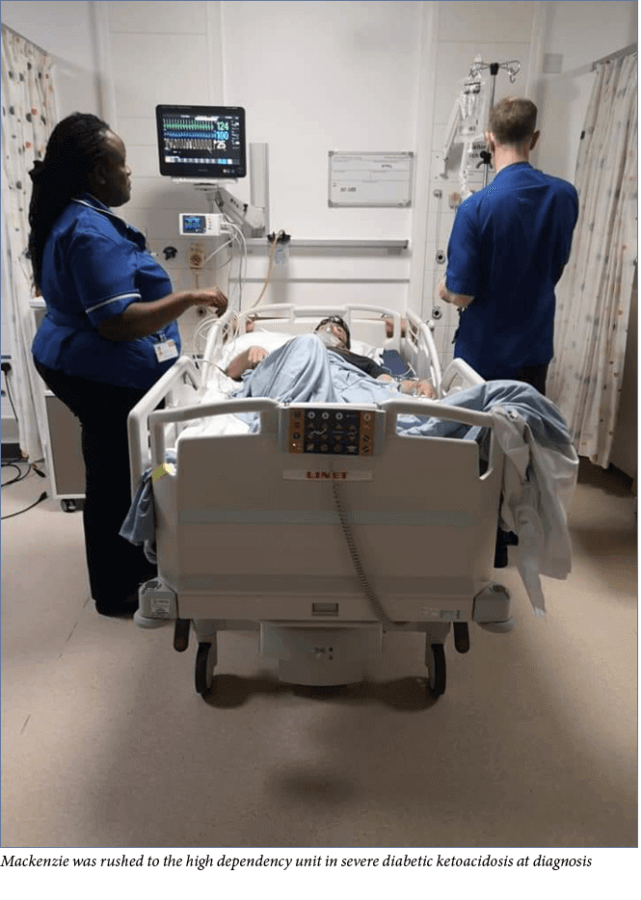

Still unhappy with the GP’s decision, my mum called her friend, who has type 1 diabetes, to come and check my blood sugar levels. My blood sugar was so high that the machine could not register it, so off we went to hospital, where I was immediately rushed into the high dependency unit.

Everything from there is a bit of a blur. I remember being overwhelmed and feeling very vulnerable. I was immediately attached to a lot of machines to monitor my heart rate, blood pressure and respiration rate, all of which were worrying. The doctors were initially unable to find a vein to get vital insulin and other fluids into me. My blood results showed that I was in severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). My mum was informed that I was very ill, and that had I gone to sleep at home that night I may not have woken up the next day. This was very upsetting for my mum, and a huge shock to me.

Over the next few days I remained in hospital. I gradually got better and moved to a normal ward but I still depended on the nursing team a lot to help with the management of my diabetes as it was very new to me and I found it hard to comprehend. The nursing team gradually showed me what to do and how to manage my diabetes. Once off the drips, I was able move to injections. Again this was very difficult. I soon grasped the concept and was undertaking this task myself in no time – the hospital staff were rather impressed.

I was discharged home after around a week. This was another overwhelming time, as we had to manage without the medical staff.

A new norm

The day after I was discharged from hospital my diabetes nurse Rachael (who just so happened to also have type 1 diabetes) visited our house to run through everything. This included learning about Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE) carbohydrate counting, which essentially meant I could eat normally and adjust my insulin dose accordingly. Although this is better than being restricted by set injections and meals, it is a difficult concept in which I have to figure out how much insulin is required for different types of food. Rachael also explained what I would need to carry with me on a day-to-day basis. This included my blood glucose metre, my finger pricker, test strips, hypo treatment, ketone metre, ketone test strips, insulin, needles… the list seemed endless! I was blown away by just how much stuff I would need to keep with me and how I was expected to remember everything.

Rachael also gave me tips on how I could fit the management of my condition into everyday life, getting into a routine of checking bloods when I woke up and before I ate, slept, exercised, etc. I found this really hard, as I am a very forgetful person; I would have often been without my things if my mum wasn’t there to remind me – in fact she often had to drive to school to bring me things I had forgotten. It was also irritating as, when I went out with friends I couldn’t just eat what I wanted. I had to think about it more consciously. I had to find something that was well-labelled or that I could easily work out the carbohydrate-to-insulin ratio for, as taking too little or too much insulin could be deadly. In addition to this, I then had to go and do a blood test and an insulin injection. This could also involve treating a hyper/hypo, which would further delay my eating. My friends soon became accustomed to this and often helped me with it, so after a while it began to feel normal. However, at the same time I resented the diabetes as I felt like it was an unwanted burden, especially during my teenage years. I felt as though I didn’t really fit in as I was different to my peers, which was difficult. It was also really hard knowing that this was now my life forever.

School, college and work

Around a week after being discharged from hospital I was able to return to school. This diagnosis came at a very unfortunate time, as I had just started Year 10 – the start of the GCSE years. This put insane amounts of stress on me. I struggled to adapt to managing both school and diabetes. My blood sugar was rarely good at school, which impacted my learning as I could not perform well unless my blood sugar levels were within a good range. This, like everything else, was really difficult. People just do not realise just how many factors there are which affect a blood sugar levels; these can include:

- The weather

- Stress levels

- Hormones

- Type of food eaten

- Exercise.

Sometimes there doesn’t seem to be a reason! I really struggled during my GCSEs and did not perform anywhere near as well as I was expected to in the exams, however I still managed to get a place in my first-choice college.

I chose a sports development and coaching course, as I wish to pursue a career in sports coaching and rehabilitation. I have really enjoyed a placement working with children with a variety of disabilities. I figured I may as well use my illness to my advantage – it gives me an understanding of how they feel, and sometimes things like this can be beneficial on a coaching profile. It is an insight that others (without a long-term condition) would not have. Luckily, the head of my course was also very clued up when it comes to diabetes as he has a son with the condition. As he was also my football coach during this time, he made it very easy for me to do well in my college practicals. He understood how my illness worked, so if I needed a break or a drink during training he knew why.

“I have really enjoyed a placement working with children with a variety of disabilities. I figured I may as well use my illness to my advantage – it gives me an understanding of how they feel.”

Around the time I started college I began a part-time job in retail. My employers are very good when it comes to my diabetes. They understand how it needs to be managed, so I am given the opportunity to do regular blood sugar tests, injections and attend healthcare appointments. I have a shelf in the office where my medical items go so I have access to anything I require whenever it is needed. My job can be hard with my diabetes as it entails of a lot of heavy lifting, so I am constantly active; however, I have become quite good at managing this and have never really struggled to complete tasks. Having a job has improved my level of autonomy and responsibility – both generally and terms of managing my diabetes.

Mental health

When I was diagnosed I was very upset because I had to accept the fact that life would never be the same and I would always be different. I was in a state of shock due to the fact that I knew I had been very close to death. I was overwhelmed by just how much work me and my family would have to put in on a day-to-day basis just to cope with my illness. As the shock wore off, I often felt depressed and wondered why this had happened to me. It felt like it was just my bad luck.

“I felt overwhelmed by just how much work me and my family would have to put in on a day-to-day basis to cope with my illness. As the shock wore off, I often felt depressed.”

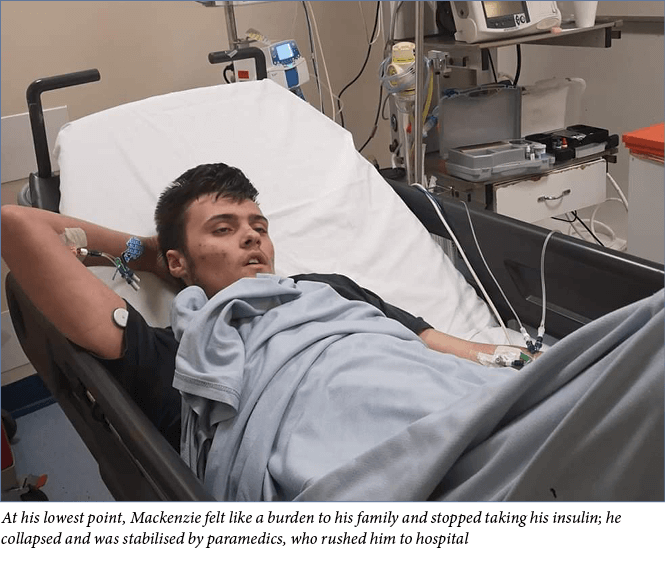

It got so bad at one point that it resulted in me trying to take my own life whilst I was staying at my grandparents during a school holiday. With this condition, this is a real risk – mental health issues are high in children with diabetes, and insulin being omitted or used incorrectly can be fatal. I felt like I was a burden on my family, as they had to deal with my mood swings when I was high or low. I lost complete interest in caring for myself and took no insulin for over a week whilst maintaining my usual eating habits. My mum called often but when she asked about my bloods I would simply make up a ‘normal’ number and say I had done my insulin so as to not worry anyone. It was easy to mislead my grandparents as they did not have a good understanding of diabetes. I could not have gotten away with it at home.

I was stabilised in the ambulance and then blue lighted straight to the hospital. By this point I was unconscious and in severe DKA. I was brought around and further stabilised before being moved to the high dependency children’s unit. I was so thirsty but was only allowed sips of water – I was so ill that drinking could have caused severe damage to my brain. Again I stayed in hospital for around a week. This time, although I had great support from my diabetes specialist nurse and team, I was referred to the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service as it was felt I needed a higher level of support. I did not want to engage with the mental health team at first – I was embarrassed – but I found it really helpful as they did not judge me and they encouraged me to talk to my mum and stepdad more, and gave me ideas on how to cope when things became too much.

“I lost complete interest in caring for myself and became very ill very quickly… I did not want to wake anyone so I tried to call the emergency services. I vaguely remember telling them that I could feel myself dying.”

After this I began to take my illness more seriously but my mum was stricter with me, constantly checking my glucose metre to ensure I had done my bloods and insulin, and not letting me do as much as I wanted to. Without this supervision I would not have coped on my own, so I suppose it was a blessing in disguise.

It is now just over a year since I was in hospital and I have much more freedom and trust. I have started paying more attention to my health (most of the time) and have learned how to work self-management into everyday life, whether it be work, football, exercise, college, socialising, etc. This has enabled me to go for nights out, now I that am 18. I know how to control my diabetes well when I drink alcohol, however my mum still makes me text her several times throughout the night to ensure that I am safe and looking after myself.

This year I have had the additional blow of being diagnosed with coeliac disease, which has been another challenge. We are slowly getting used to this.

COVID-19 lockdown

Just as I had adapted to my ‘new norm’, along came another blow: coronavirus. Due to the seriousness of this pandemic, our country went into lockdown. I was very concerned, as diabetes carries a moderate risk. Not so much that I had to completely isolate but this was still a worry.

Being stuck inside for long periods of time is having a negative impact on my mental health. I cannot socialise with friends, which is normally helpful when I am in a bad place mentally. I do, however, still have the support of my family. I can’t imagine how teenagers with this condition who do not have a supportive family must manage.

Being in lockdown I am struggling to maintain the motivation to complete my college work, as I am not physically in college and therefore not partaking in the practical side of the course, which I enjoyed. This is putting a lot of pressure on me and my family.

I work in retail, so I am not completely shut away from the outside world. I am classed as an essential worker and interact with people every day with the new safety guidelines in place. This does help me.

For now we are living this new norm. But I should be used to that!

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022