Diabetes is a self-managed condition where it is imperative that structured level-three education is provided from diagnosis onwards (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016). Self-management education improves outcomes and reduces hospital admission costs due to complications (Funnell et al, 2009). As part of an ongoing quality improvement initiative, the Hillingdon Hospitals team recognised the need to add to the current structured education programme.

The Hillingdon diabetes service supports 210 children and young people living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The multidisciplinary team consists of two paediatric consultants, four paediatric specialist nurses, a paediatric specialist dietitian and a clinical psychologist. The service runs both paediatric and adolescent clinics. The paediatric clinics (under 16 years) take place on a Friday afternoon, when all four rooms of the children’s outpatients department are available for use. While structured education for newly-diagnosed families had been well attended, previous attempts to deliver refresher education to those diagnosed more than 1 year before was poorly attended. An innovative approach, restructuring clinic time into a group-based consultation, was therefore developed.

Why is this needed?

Ongoing self-management education is essential to optimise diabetes control (Campbell et al, 2018). However, clinic time is often expended by managing the immediate concerns of the healthcare team or those presented by the family. This leaves little to no time in which a preventative approach can be taken. A further obstacle to providing prevention-based education in clinic is the difficulty in making it age-appropriate to both the child and parent simultaneously. Preventative structured education was therefore identified as a gap in care provision within the Hillingdon Hospitals service.

While the obvious answer might be to provide education outside the clinic environment, gaining good attendance at structured group education sessions – especially from families who have been living with diabetes for many years – is often problematic (Christie et al, 2014). Families’ willingness/motivation to attend hospital appointments more than the required four to five times per year can vary significantly. Patients are often quite young at the time of diagnosis and depend on the knowledge given to their parents at this time. As a result, the young person’s own knowledge may end up being inadequate for several reasons:

- It may be outdated if evidence has changed since their diagnosis

- Their cognitive maturity will have changed

- Their parents may have misunderstood information, developed bad habits or could be resistant to change.

The provision of preventive structured group education is also often hampered by resource availability, such as physical space, multidisciplinary team (MDT) time and staffing capacity, as well as the time needed to plan such sessions. To overcome the various issues and provide essential preventative structured education that is both developmentally appropriate and deliverable to adults and children simultaneously, a novel approach was developed: the annual group clinic.

Method

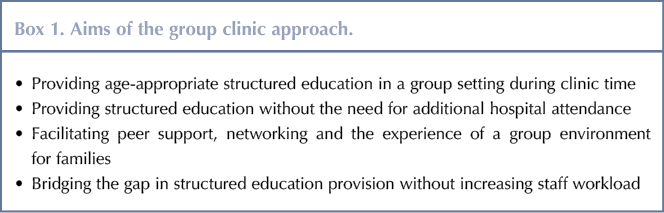

Existing age-banded clinic structures were utilised to set up the group clinics. The group clinic approach had four aims, see Box 1. Each patient and their family was invited to four clinic appointments a year: one group clinic and three traditional MDT clinics. The group clinics took place in the fourth quarter of each year. Flyers were created, see Figure 1, that were used to promote the group clinic. These were handed out in person where possible at the family’s previous clinic appointment to introduce the concept and then posted along with the clinic invitation letter, which explained the concept in more detail.

Education was delivered to young people and their parents independently of one another. The same themes were covered, although topics varied slightly depending on whether it was a parental or young person’s group. Topics in the young person’s session were delivered in an interactive and practical way. Young people were still seen for individual consultations with the consultant during the group clinic, although the timings of this varied at each phase.

All members of the MDT facilitated the groups. Continual improvements were made to

the intervention based on key learnings at each phase.

In 2017, 40 participants aged 13–17 years were identified for the intervention. All young people with type 1 diabetes in this age group were included and the groups were of mixed gender.

For each phase, the group clinics included between six and eight participants. Participants’ parents/carers were invited to attend at the same time. Interpreters were arranged to sit with parents for whom English was not their first language.

Initially the groups were clustered by age, with the closest ages together. However, due to parental requests for changing appointment dates this could not be completely maintained.

A very small number of families requested that they not be included in the process and were seen individually after the group clinic on the same day. Interestingly, having seen the end of the group, one of these families chose to join the following year’s group clinic.

Phase 1: 2017

Structured education focused on two topics:

- Alcohol and diabetes

- Exam stress and diabetes.

The MDT team worked together, using pro formas to ensure that the following actions were completed upon the arrival of each young person at the group clinic:

- Meter download

- HbA1c check

- Height and weight measured and charted

- Urine sample given

- Blood pressure taken.

Two young people were seen by the consultant prior to the group starting while waiting for others to arrive. The group education session was delivered over 90 minutes during which the consultant quietly interrupted the group, requesting one young person who had not yet been seen join them for a 10–15 minute one-to-one consultation. The consultation focused on any insulin dose changes required as a result of the meter download as well as a discussion about HbA1c. Parents were invited to join this consultation. After the consultation, the young person and their parent(s) rejoined their respective groups. Any young people who were not seen by the consultant during the education session had their brief individual consultations at the end. The clinic in this format still finished a lot earlier than normal, so no additional consultant time was needed.

The young people’s session used practical props, such as water-filled alcohol bottles and different sized glasses, see Figure 2, to facilitate education about alcohol use and its interaction with diabetes. The parent’s session included both small and large group education and discussion.

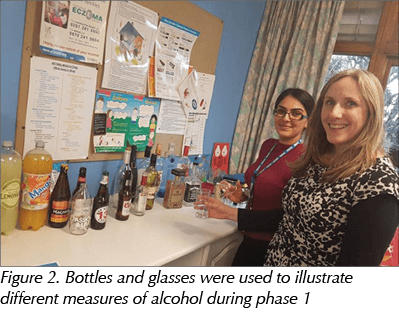

There were five key learning points identified during phase 1, see Table 1. Improvements to the clinic were made based on these points.

Phase 2: 2018

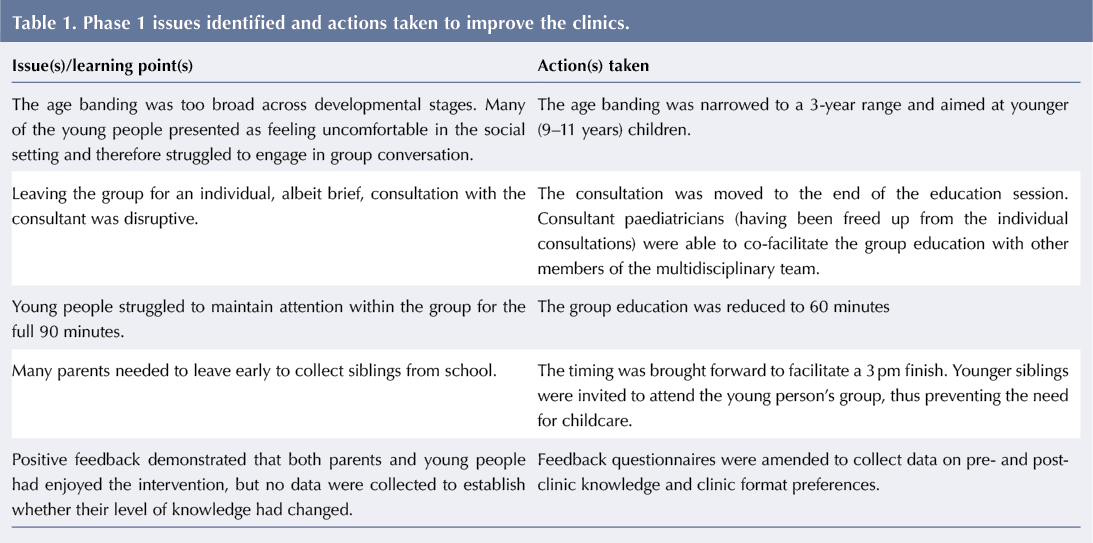

This phase educated young people about what diabetes is and safely eating out when away from parents. Their parents were taught about the physiological and psychological changes during adolescence and the impact these changes have on diabetes management.

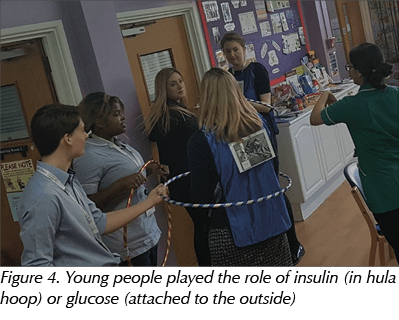

For the young people, the clinic waiting area was transformed, see Figure 3, and obstacle-style props used to demonstrate the journey of glucose through the body and the corresponding role of insulin. Young people took on the roles of glucose or insulin, going through a person-sized tunnel, the glucose attaching to the insulin with hula hoops, see Figure 4, and gaining entry into the ‘cell’ (another room) together. This allowed the facilitator to practically demonstrate what hypo/hyperglycaemia is and how it affects the body. Young people then learnt about carbohydrate counting and used web-based tools to practice. They also performed eating out scenarios.

Parents’ education was facilitated by the clinical psychologist and consultant. The session was run as an interactive workshop. Parents worked in small groups using scenarios to prompt discussion before feeding back to the larger group. The facilitator encouraged parents to examine and challenge their own beliefs about their expectations for blood glucose control over school holidays. Strategies to support good management during this time were discussed.

The changes implemented following phase 1 had a number of positive impacts on phase 2. The new format for individual consultation and overall timing of the group worked better. As a result, no parents needed to leave early to collect siblings. Engagement improved with the younger age range, therefore the team decided to develop the clinic as rolling 3-year programme for 9–11-year-olds, with new topics covered each year. Including siblings in the group clinic increased attendance and worked well.

Phase 3: 2019

In phase 3, young people focused on glucose testing and hyperglycaemia while parents learned about challenging beliefs and expectations about blood glucose testing and hyperglycaemia, see Figure 5.

The young person’s group was very interactive and included a blindfolded maze, life-size body mapping of hyperglycaemia symptomatology and a team problem-solving relay race to reduce the imaginary blood glucose level of a paediatric diabetes specialist nurse. As data on young people’s management before and after participation were not captured, it is unclear whether the activities undertaken transferred to real-life behaviour changes. The parental group focused on supporting young people to challenge their own beliefs, expectations and practices related to managing hyperglycaemia, especially during holiday periods. The group used example case studies and participated in small and large group discussions.

The team agreed that this session worked well and no major changes were made. This decision was supported by positive feedback from both young people and parents who participated.

Results

Mean attendance rates at the group clinic ranged from 82.5% to 90.5% over the 3 years. This was comparable to normal clinic attendance rates.

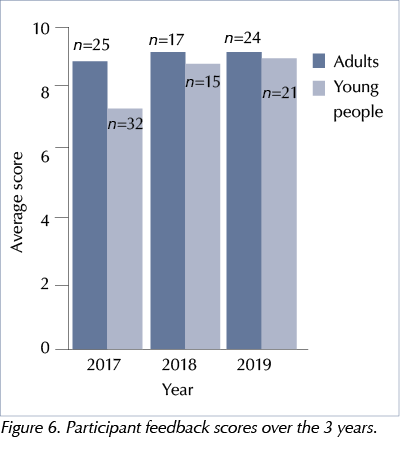

Participants rated their experience of the group clinic on an evaluation form, where 1 represented ‘not good’ and 10 ‘very good’. Young people (n=68) rated the clinic between 8 and 10 (mean=8.6) and the mean parent rating (n=66) was 9/10, see Figure 6. Knowledge was evaluated using the same scale. Mean average self-evaluated parental knowledge improved from 6/10 before the group experience to 9/10 afterwards.

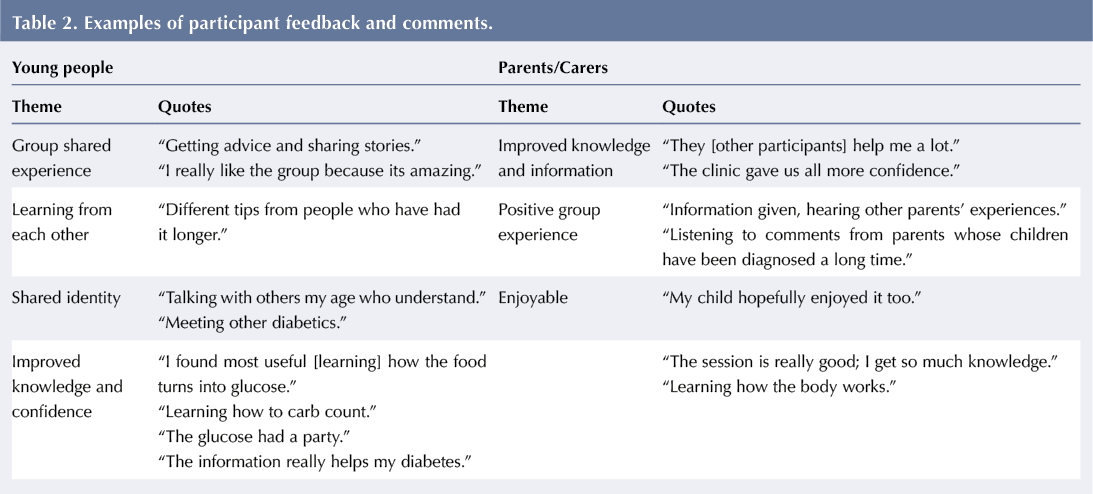

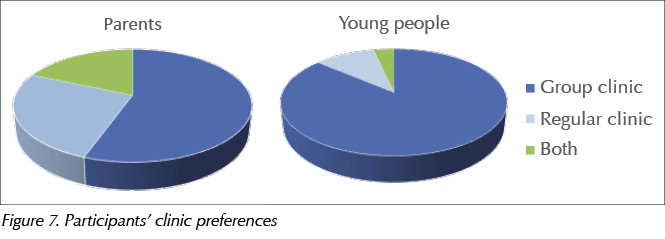

Following attendance at the clinics, feedback from the young people and their parents/carers, highlighted different themes, see Table 2. Young people reported a strong preference for the group clinic format while parents’ preferences were more varied, see Figure 7.

Healthcare professionals’ reflections

All members of the MDT were asked to provide feedback on the group clinics. Consultants reported that they enjoyed delivering clinics in the group format and that their initial concerns regarding possible rejection of this clinic style were quickly allayed. The dietitian welcomed the opportunity to provide education in a group session, particularly as they were able to give practical demonstrations. The paediatric diabetes specialist nurses reported that the clinic structure provided a great forum for introducing children, young people and their families to each other while providing age-appropriate education in a resource-efficient manner. The clinical psychologist thought that the group experience provided a great opportunity to normalise life with diabetes for this cohort of young people and develop peer support networks.

Outcome and next steps

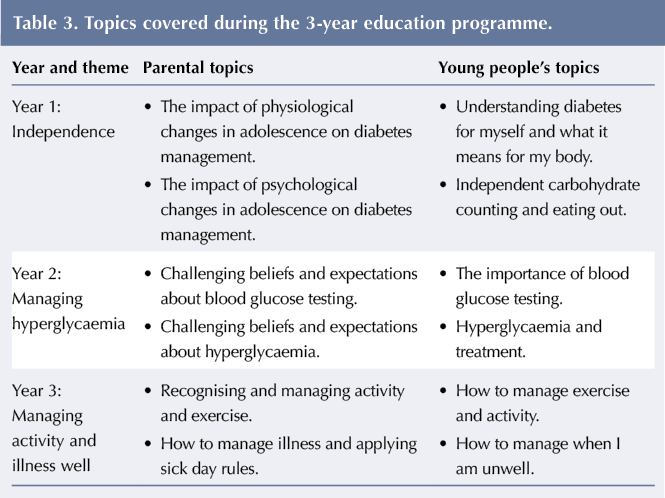

The group clinic has become embedded into the yearly service work plan as a 3-year rolling programme for all 9–11-year-olds and their families, see Table 3. Parents reflected that it had improved their self-management skills and delivered a positive group education experience. Group clinic also provided an additional opportunity for MDT members to learn from each other and develop group education delivery skills.

There are hopes to build on the level of engagement and positive experiences reported following the initial clinics in order to deliver group-based structured education to patients in additional age ranges (adolescents and younger children). This will allow the coverage of topics relevant to adolescents, as was attempted in phase 1 of the intervention, in clinics for teenagers. The focus of clinics for 6–8-year-olds will be on prevention through conversation around typical fears and anxieties, increasing knowledge and providing a peer support network from a much younger age. The more opportunities provided to enable families and young people to interact, the more likely it is they will develop relationships that extend well beyond the clinic experience. In time, it is hoped that young people who have gone through group education will be included as co-facilitators in the process, acknowledging the valuable and unique knowledge, skills and understanding that they have to offer. There are also plans to collect data to measure the transfer of skills learnt via this model to everyday life.

Conclusion

The group clinic model provides a framework for the cost-effective delivery of structured education within diabetes services. Both young people and parents report that they not only enjoy the group experience but gain knowledge and peer support in a way that cannot be achieved in individual consultations. Delivering structured education as a team improves the consistency of information given to families, which is a frequently recognised issue within the network.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022