The period of adolescence and a new diagnosis of type 1 diabetes (T1D) both represent times when there is an increased risk of mental health issues (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016). Additionally, adolescents with T1D – especially females – are at an increased risk of developing eating disorders or disordered eating behaviour (DEB) than their healthy peers (Hanlan et al, 2013; Hastings et al, 2016). The World Health Organization (2019) highlights the importance of meeting adolescents’ health and developmental needs and providing an anticipatory service that considers both biological and gender-based differences. This article explores the links between body image and DEBs in the T1D adolescent population to raise awareness of the issue and consider how practice could be improved.

Terminology

The term ‘eating disorder’ is a clinical diagnosis that encompasses a range of behaviours related to food, including skipping meals, self-induced vomiting, negative body image and DEBs. ‘DEB’ is more of an umbrella term to describe a variety of disturbed eating behaviours including binge eating and diet restrictions. In people with T1D, a further problematic behaviour is the intentional omission or restriction of insulin, which can be used to control weight (Araia et al, 2017).

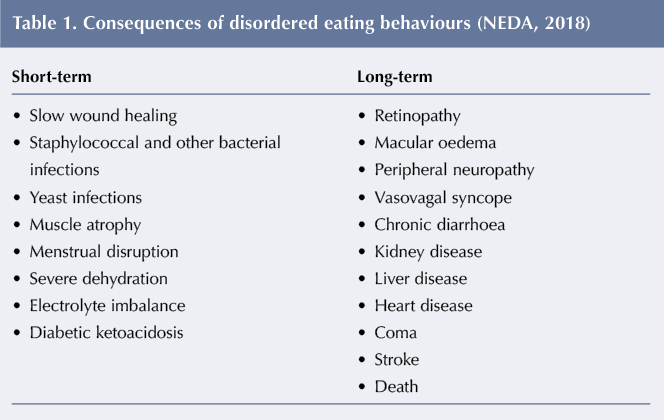

While there is increased recognition of eating disorders as a mental health issue, DEB is not given the same attention or clinical diagnosis. The two terms seem to be used interchangeably for a variety of behaviours, however there is a significant difference between a diagnosed eating disorder and DEB in severity and frequency of occurrence (Hanlan et al, 2013; Woodfield, 2017). Regardless of the terminology used, these behaviours result in increased risk among people with T1D as they have a significant impact on blood glucose levels, leading to both long- and short-term complications for adolescents (Racicka and Brynska, 2015), see Table 1.

Challenges of adolescence

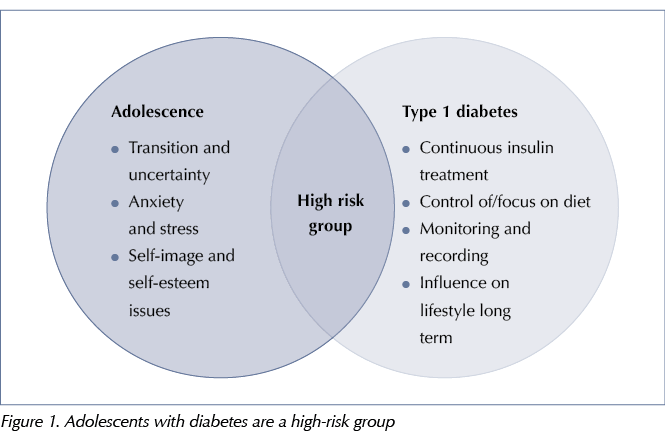

Adolescence is a time of increased independence and part of the transition can include an increase in risky behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol use and unhealthy dietary behaviours (Hanlan et al, 2013), see Figure 1. During adolescence the additional burden of T1D heightens focus on dietary intake, portion precision and carbohydrate counting, adversely affecting attitudes and feelings towards food and eating behaviours (Araia et al, 2017). Many theoretical perspectives propose an association between body and self-image, and there is evidence that body dissatisfaction increases during adolescence and is partly linked with body changes (Vilhjalmsson et al, 2012).

The diagnosis of a long-term condition, such as T1D, during adolescence could consequently lead to increased issues around body image and self-esteem. This supports Frank’s (2002) ideas of illness in relation to the body being ‘broken’, which relates to the impairment of expected or normal functions. Adolescents who perceive themselves to have dysfunctional bodily characteristics consequently develop negative perceptions of their own self-image and body dissatisfaction (Vilhjalmsson et al, 2012).

Diabetes and food are closely linked, as control of food becomes an important daily task. Consequently, adolescents with T1D can easily become fixated on food and develop a negative body image (Diabetes UK, 2019).

The focus of social media on appearance promotes social comparison (Hanlan et al, 2013). The rapid expansion of social media has therefore increased challenges for adolescents who may already be insecure about their body image. It is thus unsurprising that the prevalence of DEBs in adolescents with T1D has been found to be as high as 37% in females and 15% in males (Hanlan et al, 2013).

Prior to receiving a diagnosis of T1D, weight loss is a common side-effect of the body breaking down its own energy stores, however once insulin therapy is started weight gain resumes. Bermudez et al (2009) found that this weight gain often leads to internal conflict around what is an appropriate body size. Research carried out by Kay et al (2009) identified a constant battle between feeling well through good control of diabetes and wanting to be thin but facing increased risks of complications and ill health.

Diabulimia: a dangerous and under-recognised condition

‘Diabulimia’ is a term coined by the media to describe DEB in people with (primarily) T1D (National Eating Disorder Association [NEDA], 2018; Diabetes UK, 2019). This dangerous practice involves intentionally reducing, skipping or stopping insulin in order to lose weight with life-threatening consequences. The development of autonomy and self-care during the adolescent period – alongside a greater use of insulin pumps – can lead to suboptimal diabetes control, as the use of insulin pumps can make insulin misuse easier. Although excellent for long-term outcomes when used effectively, incorrect use increases the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (Hanlan et al, 2013). This is because fast-acting insulin delivered by the pump is usually the only insulin given and there is a lack of longer-acting insulin in the body to act as a ‘safety net’.

The NEDA (2018) states that – while the body is very resilient and people can function normally with raised blood glucose – the control of weight through the manipulation of insulin levels can lead to irreversible long-term damage. The Association further states that, even in the absence of obvious problems, skipping insulin regularly can shorten life expectancy by 13 years (NEDA, 2018). However, adolescents may not consider the long-term impact of their behaviour. This is a result of biological changes that lead to a perceived invulnerability (Nightingale and Fischhoff, 2001). This means that the long-term risks associated with certain behaviours (see Table 1) are underestimated, leading to an increase in risky health behaviours.

While society is becoming more aware of mental health issues in young people, diabulimia is not generally recognised as a mental health condition and there is limited understanding. Therefore, healthcare professionals and family members do not have the information they need and are unlikely to look for and recognise signs of diabulimia. Yet this is a serious concern, given that 4 in 10 young women and 1 in 10 men aged 15 and over admit to skipping insulin to lose weight (Diabetes UK, 2019). The various physical and emotional/behavioural signs of diabulimia are listed in Table 2.

Hurdles to optimum treatment

Hastings et al (2016) and McNicholas et al (2016) assert that individuals with eating disorders are routinely stigmatised by health professionals, being viewed as challenging and perceived as difficult to treat. Tierney et al (2009) highlight that this is also the case with patients who have diabetes, therefore those presenting with both conditions may be further disadvantaged.

An additional complication in this population of patients is that the treatment for eating disorders and that for optimum diabetes management have conflicting goals that are a source of potential issues (Goebel-Fabbri et al, 2009). Therefore, if diagnosed with an eating disorder, individuals with T1D tend not to respond to standard treatment. Adolescents with T1D and DEB are also at a higher risk of serious complications related to glycaemic control, which needs to be more fully understood. Recovery rates are lower in this population, which suggests another approach is required that encompasses the more complex needs of this patient group.

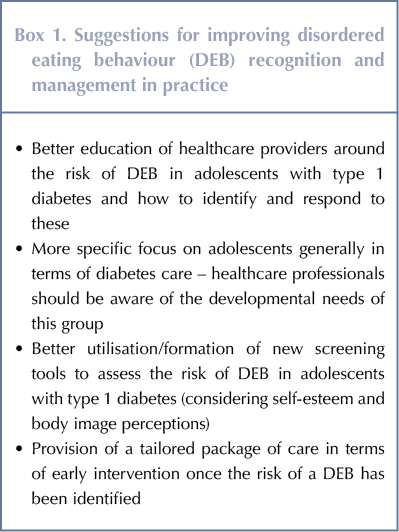

Recovery could be further hindered due to a lack of professional awareness and poorly-tailored health services, demonstrating the need for a more bespoke provision.

Troncone et al (2018) found that a significant indicator for the development of DEBs is the degree of body dissatisfaction experienced. This impaired perception of body size and degree of body dissatisfaction could be due to the greater emphasis on the body for young people with T1D. Normal changes in the body during adolescence, the influence of social media, the effect of T1D and insulin therapy on the body, and the pressure of managing the condition may all exacerbate concerns around body image. Given the potential consequences for adolescents with T1D who display DEBs, service providers should be more vigilant, even when young people appear to be below the threshold for clinical diagnosis in terms of symptoms and weight loss. This is particularly important as DEBs often begin during adolescence and, if they remain unidentified and untreated, they increase in severity over time (Hanlan et al, 2013).

Tackling DEBs in practice

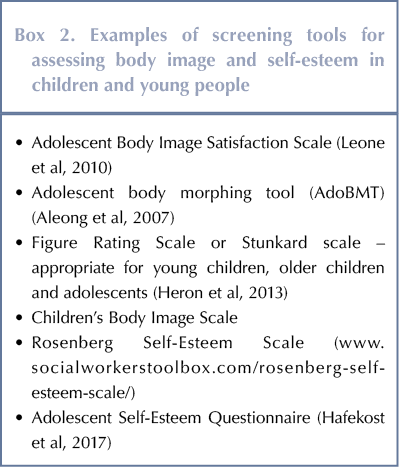

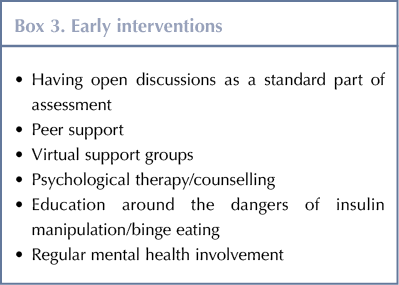

There are various training needs and ways in which practice can be improved, see Box 1. However, there are several steps that can be taken to improve the recognition and support that adolescents receive. Assessment and identification of body image dissatisfaction/low level of self-esteem may be useful in the development of early intervention strategies at diagnosis. This may include early screening for risk factors (see Box 2), early intervention where there is a higher risk (see Box 3) and – where possible – prevention.

There are several tools that can be used to assess body image. These include tools that do not use any visual presentation of a body image, such as questionnaires, as well as tools that use mock body images/silhouettes or distort real body images, such as distorting mirrors, video-based distortions and computer morphing software (Aleong et al, 2007).

Peer-to-peer or expert support groups may be effective in providing support and the potential for a more open discussion about the issues faced. Technology has increased the number of ways in which such support can be provided, eg text messages, online forums websites (eg healthtalk.org) and telehealth.

Finally, there needs to be greater awareness of the links between heightened risks in adolescence and widespread pressures that are exacerbated through social media images that might seem even less obtainable for a young person with T1D.

Conclusion

Body dissatisfaction, eating disorders and DEBs are more common in adolescents with T1D than in their healthy peers. While usually more prevalent in females, DEB should not be dismissed in males. Better awareness and training for healthcare professionals around the identification of risk factors for DEBs is needed to improve outcomes.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022