In 2011, the Department of Health (DH) introduced in England the mandatory Best Practice Tariff (BPT) for paediatric diabetes (DH, 2011). This provides an annual payment to service provider units for the treatment of all children and young people (CYP) under the age of 19 years with diabetes, if certain criteria for high-quality care are met. One criterion is that the provider unit must provide evidence that each patient has received a structured education programme, at initial diagnosis and through ongoing updates, that is tailored to the needs of the CYP and their families.

NICE (2016) advises that all CYP with type 1 diabetes using a multiple daily insulin injection regimen or insulin pump therapy should be offered level 3 carbohydrate counting education. Funding through the BPT allowed the Exeter Children and Young People’s Diabetes Service (ExCYPDS) to have sufficient dietetic resources to provide this education to all CYP newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, before discharge from hospital. However, diabetes education needs to be a continuous process to be effective, and this is particularly important in paediatric settings, as children gradually take more responsibility for their carbohydrate counting as they mature (Lange et al, 2014; Smart et al, 2014).

There are no nationally evaluated or accredited carbohydrate counting programmes for CYP with diabetes or their parents and carers (Campbell and Waldron, 2014). In Exeter, uptake of the existing locally developed carbohydrate counting programme was poor, and the integration of regular carbohydrate counting education into the care of CYP needed to be re-evaluated. ExCYPDS developed a new programme for two age groups to actively learn carbohydrate counting skills in a real-life setting: Cook and Eat Family Fun, for children of preschool (0–4 years) and primary-school age (5–11 years); and Cook and Eat Fun, for young people of secondary-school age (12–16 years).

This article describes how the programme is run and funded, and the benefits of the programme for CYP and their families.

The Cook and Eat programme

Since 2015, all CYP with type 1 diabetes within ExCYPDS have been invited annually to attend a Cook and Eat programme until they leave secondary school. The programme was developed by one of the authors (ML) and piloted in 2014 with a secondary school in Exmouth. The aims were to identify the carbohydrates in food and to be able to calculate them using Carbs and Cals, food labels and reference tables. Initially, a wide range of foods were prepared in one of four sessions, one week apart.

The lesson plan was too ambitious and recipes too complex and difficult to administer with one facilitator. Following the pilot, the sessions were simplified, an additional facilitator recruited and two sessions offered to allow more schools to take part. The Family Fun sessions started in the summer of 2016.

CYP are invited to a session based on their school year and the programme cycle commences in September. Children attending the Cook and Eat Family Fun programme are invited with their parents, carers and siblings to a 2-hour session held in the suitably equipped food technology room of a local secondary school. Young people attending the Cook and Eat Fun programme are invited to bring a friend. The programme consists of two 90-minute sessions at a limited number of local schools. A session is run in half-term for CYP who have not had the opportunity to attend at their own school. The CYP prepare and cook a savoury and a sweet course. Recipes are quick to prepare, healthy and require few technical skills, allowing children of all ages to participate. They are changed annually to reduce preparation time between sessions and allow non-perishable ingredients to be used for multiple sessions. CYP are able to administer their insulin and eat the food they have prepared after calculating the carbohydrate content.

Inspired by the Teaching Skills for Healthcare Professionals course offered by Sheffield Hallam University, guidance was sought from the education sector on novel ways to educate CYP about food. Educationalists Chickering and Gamson (1987) stated that learners must do more than just listen if they are to learn effectively. They must read, write, discuss or be engaged in solving problems. When students are “actively learning” they are engaged in analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

People may utilise different learning styles to engage in education (Dunn et al, 2002). The VARK model (Fleming, 1995) highlights four distinct methods of learning: visual, aural, reading/writing and kinaesthetic. The Cook and Eat programme aims to engage all learning styles through experiences that are:

- Tactile: giving young people the food packets and ingredients.

- Kinaesthetic: preparing and cooking food.

- Visual: using pictures to accompany cooking instructions.

- Aural: giving spoken instructions and having group discussions.

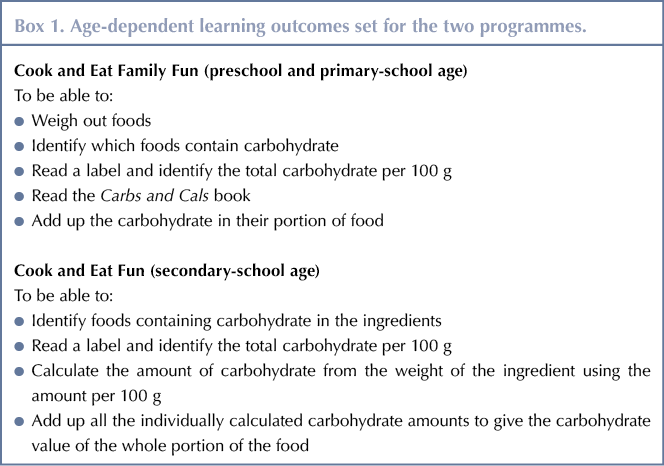

Age-dependent learning outcomes have been set to be achievable for all young people attending (Box 1). Cook and Eat follows the philosophy, principles and practice of education of children, adolescents and their parents as defined by International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) Clinical Guidance (Phelan et al, 2017). Lesson plans defining teaching activities and learner activities are written for each learning activity within the planned timescale. These ensure reproducibility between sessions.

Sessions are offered on an annual basis to build on the foundation of knowledge and understanding acquired in previous years. Optional additional activities are planned within the session structure to accommodate different ages and abilities.

Assessment of learning is made by informal observation of tasks, questioning during group work and evaluation of worksheets used for carbohydrate counting.

Risk assessments

These are aligned to the school’s risk assessment procedures, and the principal facilitator holds current food hygiene certification. Food hygiene certificates are not essential and information on good practice can be found on the Food Standards Agency website (https://bit.ly/2q2Ef5z).

Parents attending Cook and Eat Family Fun remain responsible for their children and, therefore, support them with knife, oven and hob safety. The secondary-school-aged children are supervised by the facilitators, who conduct a safety briefing before each session. Additional facilitators (students, dietetic assistants, nurses and regional dietitians) support the principal facilitator.

The family sessions can be delivered with one facilitator, as parents remain responsible for supervision. The presence of one or two additional support workers is useful to help families with multiple or young children and to assist with washing up. Secondary school sessions require a minimum of one additional person.

The principal facilitator needs to have an interest in food preparation, an awareness of carbohydrates, and the ability to teach all ages and abilities of young people about maths. The facilitator should be a member of the team who knows the CYP and their history, so that there is an existing relationship and the session can be targeted more effectively. It is also important to have a trained diabetes professional to facilitate unstructured discussions about diabetes (Phelan et al, 2017) and to manage a first-aid or diabetic emergency should one occur.

Cost

The Cook and Eat programme is free to attend for all CYP and their families and friends. Schools have allowed use of their facilities free of charge and have funded ingredients used by their own pupils through the pupil premium. The annual cost of delivering the Cook and Eat programme is under £500.

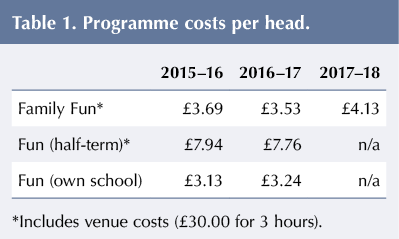

In 2017, a grant was obtained from the Norman Family Charitable Trust to fund 4 years of the programme. Donations from Tesco, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s also supplement Family Fun ingredients. It is hoped that further donations and support could be sought from the same companies. Local diabetes support groups have also offered to fund Cook and Eat. Costs per head are provided in Table 1.

Assessment

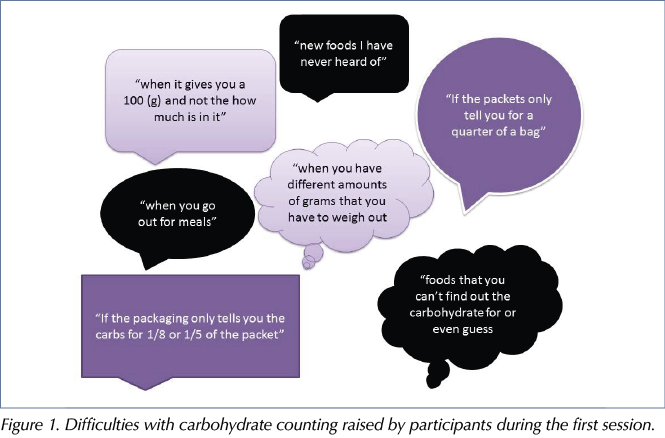

CYP attending the Cook and Eat Fun programme are set a paper-based carbohydrate counting quiz at the start of the first session to assess their knowledge. They are also asked about who takes responsibility for carbohydrate counting in the family and what they would like to learn about diabetes. This enables additional help to be targeted at those who require most support. Figure 1 provides details of specific difficulties with carbohydrate counting identified by CYP in the first session.

Facilitators observe CYP working as a group to calculate the carbohydrate content of the foods they prepared. This allows for informal assessments of their numeracy skills and usual level of independence with carbohydrate counting. The group task also allows older or more able individuals to support those that are younger or less able. With annual attendance, the facilitators are also able to observe progression in abilities and check retention of learning from previous sessions.

CYP in younger age groups complete simple addition tasks independently, while the more complex recipes have the carbohydrate counted for them. Facilitators use visual maths techniques, such as bricks, counters, worksheets and pre-prepared stickers, with the correctly counted carbohydrates written on them.

Attendance

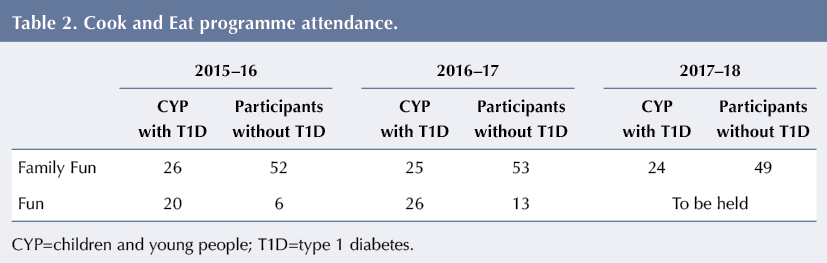

Attendance on the Cook and Eat programme has increased since its initial introduction. In 2016–17, 42% (51 of 122) of the age-eligible ExCYPDS caseload of CYP with type 1 diabetes attended, an increase from 38% (46 of 122) in 2015–16 (Table 2). An additional 66 participants (13 friends, 19 siblings and 34 parents) also benefited from the education in 2016–17.

The rate of uptake was greater for CYP invited to attend a Cook and Eat Fun session during term time in their own school than for sessions during the half-term holiday at another venue. Of those invited in 2015–16, 58% (15 of 26) took up a place in their own school compared to 17% (six of 35) in half term. Similarly, in 2016–17, 53% (16 of 30) took up invitations to attend at their own school compared to 19% (10 of 54) for a half-term session.

CYP enjoy attending Cook and Eat Family Fun each year, with 17 having attended 2 years and 7 all 3 years. Twelve CYP attended both years of the Cook and Eat Fun.

Feedback

Positive feedback on the sessions has been consistently received from CYP and their families. Feedback was provided via single-word summations of their experience of Cook and Eat, to be used in a word cloud, and via responses to written questions. Figure 2 illustrates the single-word feedback from Cook and Eat Family Fun sessions held in 2015–16. Parents enjoy meeting other families in the same situation and often meet up outside of Cook and Eat. CYP ask regularly when the next session will be held and what they will cook. The sessions help parents with practical ideas for continued engagement with carbohydrate counting at home.

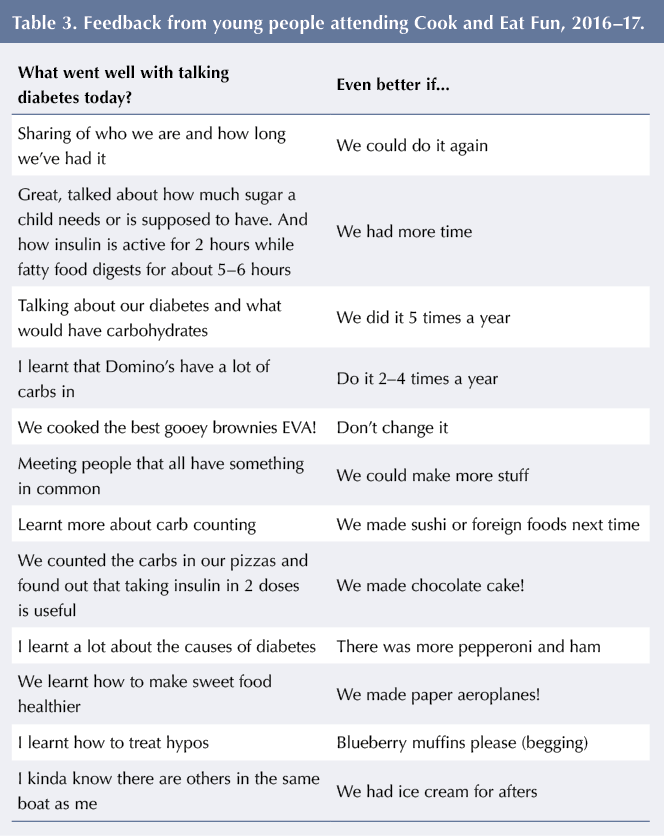

Table 3 contains written feedback from young people at Cook and Eat Fun about what went well and what could be improved from sessions held in 2016–17. CYP wanted more sessions each year and, when asked what they would like to cook, frequently requested cake. Each group is slightly different, and the topics and conversations are led by the CYP. It is noted that CYP in the Fun sessions talk more openly about difficulties they experience about managing diabetes. This contrasts with the Family Fun sessions, when parents are present. Many value the discussions around diabetes, learning new facts around insulin action, glycaemic index and hypos.

Discussion

The Cook and Eat programme highlighted the wide range of abilities held by the participants, and the need to have tasks that are clear and simple to understand, with more challenging tasks available for those of higher ability. It became apparent that some CYP had poor literacy skills, so a move was made to support recipes pictorially. Modifications were also made as the programme progressed to simplify the numeric tasks and reduce the complexity of the carbohydrate counting, accommodating the numeracy difficulties experienced by some participants. The aim was to make numeracy tasks associated with carbohydrate counting fun, interactive and achievable, so that it was a positive experience.

Engagement with the programme has been high, with 42% of the age-eligible caseload attending in 2016–17. This may be due to the programme being easily accessible at a local venue and free to attend, and food being provided to eat or take home. Seven CYP have attended the Family Fun programme in three consecutive years, and it is anticipated that the uptake for the secondary-school-aged group will continue to increase as the younger children who attended and enjoyed the family group become eligible to attend. Young people appeared to enjoy the peer support, with comments indicating that they felt less alone with diabetes and that they valued meeting others with type 1 diabetes in their school.

Peer support in adolescence is imperative in creating a supportive environment. Adolescents glean more encouragement in terms of emotional support from peers than from family members (La Greca et al, 1995). Friends were invited from the second year to increase attendance, with over half taking up the offer. We have found that the large groups with peers generated more active participation and discussion. Peers asked more about the condition, which led CYP to talk more about their feelings and expectations of diabetes day to day. It helps friends to have a better understanding of diabetes tasks.

One mother commented: “His friend said that, although he’s not diabetic, he’s going to count his carbs at home to see what he has to do every day. Another member of my son’s back-up squad, I think!” Peer support has been associated with more compliance with diabetes self-management (La Greca et al, 1995).

Despite the good uptake, a number of young people were still unable to commit to attending. For the Cook and Eat Family Fun session, this appeared to be due to difficulties getting transport to the venue, or holiday and work commitments. Acceptance of invitations for CYP to attend a Fun session at their own schools was greater than for invitations to attend a half-term session. This may be a result of the relative ease of attending after school, eliminating transport concerns, capitalising on familiarity with the venue, and avoiding conflicts with school holidays and parental work commitments. Uptake in half-term may also have been reduced by fears about meeting new people with type 1 diabetes, reluctance to visit an unfamiliar school and being unwilling to give up time away from school for diabetes.

The primary aim of the programme was to engage children with ongoing learning about food, carbohydrates and the principles of carbohydrate counting. It would be helpful to identify a validated tool to assess skills and knowledge of carbohydrate counting. There have been no appropriate measures of carbohydrate competency available to date; however, an assessment tool is currently being developed by another paediatric diabetes team (Anna Carling, personal communication, 11.09.17).

The Cook and Eat programme does not fulfil all the ISPAD requirements of structured education as it does not currently have a defined quality assurance programme (Phelan et al, 2017). Although patient experience is audited, a more robust evaluation of the clinical benefits of attendance is needed. Reasons for improvements in HbA1c are multifactorial and difficult to assign solely to a brief intervention. Those attending education are often the most engaged, well-informed or high-functioning families, so experience a less noticeable impact on physical or psychological health (Coates et al, 2013). Despite the limitations, HbA1c, weight and lipid levels may all indicate benefits of participation and should be considered for future evaluation.

ExCYPDS has offered diabetes self-management education sessions to individuals in the post-16 age group, but these ultimately did not take place owing to lack of uptake. It is common for adolescent CYP to not engage with group-based activities (Price et al, 2016), particularly those with high HbA1c (Christie et al, 2014). The facilitators of Cook and Eat have not yet offered a programme for this age group, but it is one potentially beneficial avenue of future development. Any such programme would have a different emphasis and be tailored to the needs of this emerging adult population. For example, it could include life skills, such as food shopping, budgeting and quick, nutritious meals as preparation for university or independent life away from the family home. It is hoped that those who graduated through the Cook and Eat programme in their younger years will continue to engage after they turn 16 years old.

Future plans

ExCYPDS have set a number of aims related to the development and assessment of the initiative:

- Increase accessibility by providing sessions in as many secondary schools as possible where there are at least two CYP with type 1 diabetes. Additional venues for the preschool and primary-school age group will be introduced across a wider geographical area, and sessions planned at the start and end of the school summer holidays.

- Measure outcomes more robustly, using a carbohydrate-counting competency questionnaire, when developed, pre- and post-session. Consideration will be given to track HbA1c, BMI and other clinical parameters.

- Engage young people post-16, in sessions entitled Cook and Eat on a Budget, introduced at a local college with the aim of providing healthy, low-cost recipes for individuals living independently, either at university or otherwise away from their family homes.

The Cook and Eat programme is easily reproducible by other paediatric diabetes teams. Clearly written lesson plans, recipes and risk assessments have been produced, and have been made available following presentation at the British Dietetic Association Diabetes Specialist Group (Paediatric Sub-Group) on 23 September 2016. Resources may be viewed at Quality in Care Diabetes (https://bit.ly/2ua9p08) and more available on request from the author. The team also welcome informal visits and observation of sessions in action.

The programme was commended in the 2017 Quality in Care Diabetes awards, in the Empowering People with Diabetes (Children Young People and Emerging Adults) category. It has also been shortlisted for the 2018 HSJ Value Awards in the Clinical Support Services category.

Conclusion

Cook and Eat is a fun vehicle for enabling healthy food choices and practical cooking skills, and for supporting carbohydrate education. It enables assessment of knowledge and skills in carbohydrate counting, and combines resources for supporting CYP and families who struggle with literacy and numeracy. Engagement with the programme has been high from CYP, siblings, peers and parents, and the ExCYPDS team are grateful to the schools that support the venture. The programme in Exeter will continue and it is hoped that more CYP will develop their skills and confidence with carbohydrate counting through engaging with food through the Cook and Eat programme in future years.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022