Parents of children diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D) play a key role in helping their child adjust to and manage both the short- and long-term impact of the condition (Anderson et al, 2002; Shorer et al, 2011).

Research demonstrates that parents hold a high level of responsibility, are often the primary source of support for their child and provide an important link between the child and their diabetes team (Drotar, 2006; Pate et al, 2015). Indeed, this parental involvement is associated with improved quality of life and better metabolic control in children (Helgeson et al, 2008). Unsurprisingly, however, this can come at a cost of parental mental health. Approximately 20–30% of parents report clinically significant levels of distress, alongside symptoms of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress (Jaser et al, 2008).

Given the importance of parents in supporting better health and quality-of-life outcomes for their child, combined with the impact of this responsibility on their own mental health, the need for parent-based interventions is paramount.

Although the diabetes team at Bedfordshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust had previously provided face-to-face support groups for parents of newly diagnosed children with T1D, the mode of delivery was revised due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the group was delivered virtually using Microsoft Teams. The team was keen to draw upon an Experts-by-Experience/Peer Support model (D’Urso and Ramful, 2020) and therefore considered it crucial to have the input of a parent whose child(ren) had been diagnosed with T1D, in order for them to be able to speak from their experiences. A number of expert parents were invited to speak, but only one was available on the day. Box 1 details the expert parent’s experience of co-facilitating the group.

Adaptations for virtual delivery

Some minor changes were also made to the group content:

- In order to make the group more interactive given the virtual nature, parents were asked to introduce themselves to the whole group, including their child’s name and how long their child had been diagnosed.

- The “chat” function was utilised in order for parents to ask questions without having to speak. Parents were also encouraged to express their hopes for the session.

- The “top tips” content was included in order to make the material more functional to parents, and they could take a copy of the slides away following the session. Tips ranged from things like how to manage strong emotions that the children may feel, managing difficult questions and the impact of language, as well as the importance of routine and boundaries.

Method

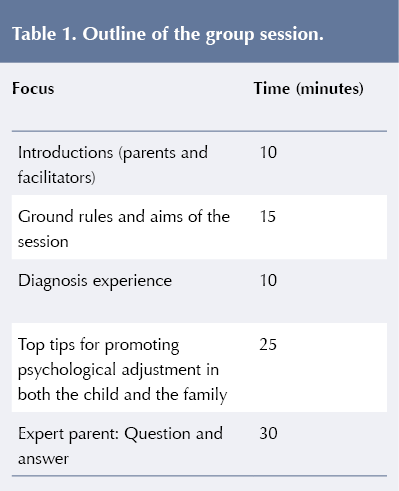

Invitations were sent by post to all parents of children diagnosed with T1D in the past 12 months across the two hospital sites. Invitations were also sent via the Digibete.org website. Invitations were sent to 39 families; 13 parents replied to the invite and 12 attended on the day. The session lasted 1.5 hours and took place in the afternoon. Table 1 (overleaf) provides a visual outline of the group and approximate timings. The Psychology Team, comprising two qualified clinical psychologists, one trainee clinical psychologist and one student psychologist, were joined by a specialist paediatric diabetes nurse and paediatric diabetes dietitian.

Participants

A mixture of fathers (n=4) and mothers (n=8) attended the group. The children with T1D ranged in age from 3 years to 14 years. Questionnaires investigating parental confidence, sense of isolation, ease of accessing support, and worry about their child and their condition were completed online before and immediately after the group.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires were developed by the authors based on the aims of the session. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. This included aims to increase parental confidence in how to access support for both themselves and their child; decreased feelings of isolation; increased knowledge of how to support their child emotionally; improved ability to liaise with their child’s medical team, and decreased worry about their child and their child’s future.

Questionnaires were completed online (via Google Forms) just before the group, and the link was sent again to re-complete the questionnaire after the group.

Feedback from the questionnaire

Although not all parents completed the post-group questionnaire (n=5), there were general trends in the findings, which we considered to be helpful for those considering future groups.

Results

Quantitative feedback generally showed positive shifts in parental confidence across all domains immediately following the group. With regard to parental confidence in managing their child’s diabetes from an emotional point of view, figures showed that 9.1% reported feeling “confident” prior to the group, compared with 100% of parents after the group.

The proportion of parents who felt “confident” or “very confident” in accessing parental support, if needed, also increased from 45.5% before the group to 80% after the group. Finally, the proportion of parents who felt “confident” or “very confident” in accessing support for their child, if needed, increased from 36.4% before to 80% following their attendance to the group.

There was also a positive change in the domains measuring mental wellbeing and support. The proportion of parents reporting “never” or “almost never” having trouble getting support from others increased from 18.2% before the group to 40% after the group. Furthermore, while 36.4% of parents reported that others “often” or “almost always” do not understand their family’s situation, such feelings were not reported following the group, with 20% of parents reporting “never” feeling this way.

In addition, 54.5% of parents reported “almost never” finding it hard to talk about their child’s health with others before the group, which compares to 60% of parents “never” finding it hard after the group. The proportion of parents reporting “never” or “almost never” having difficulties telling doctors and nurses how they feel also improved from 63.7% before the group to 80% after the group.

Following the group session, a greater percentage of parents reported “almost no worries” about how others’ will react to their child’s condition (40%), compared with 36.4% prior to the group. Finally, the proportion of parents who “often” or “almost always” felt worried about their child’s future reduced from 54.6% before the group to 40% after the group.

Feedback from parents

The team invited parents to describe what they found most and least helpful about the group. Themes included:

1. Connection with others

Most parents commented on the helpfulness of being able to connect with other parents.

“It was really useful to hear what everyone was saying.”

“[it was helpful to] see others who were going through similar experiences.”

“realising we are not alone.”

“talking things through and to hear that others’ concerns are the same concerns we have.”

As previously mentioned, although the group is usually facilitated in person, due to the COVID-19 pandemic the current group was adapted online. This did have an impact on one parent’s experience of being able to connect with others:

“It’s difficult on MS Teams for different people to speak, but it is better to have the meeting virtually as opposed to not at all.”

There was also a suggestion to improve connection by splitting future groups in terms of the age of the child:

“I think children with diabetes should be more age related. Under 5 and primary school kids and secondary school kids. I think the age would be better working than all together, as many parents in the groups had children around 9–10 years have many of the same aspects in the group.”

2. Advice and reassurance

A number of parents commented on the helpfulness of getting advice from the team as well as having their questions answered by an expert-by-experience parent who had navigated many of the obstacles they were currently facing (such as problems with education or peers).

“It was helpful to get lots of great info.”

“It was really helpful… to be able to ask questions to [expert parent] who has such an incredible personal experience.”

One parent also hinted at the reassurance they received from the group in terms of their strengths and resources in managing a very distressing time.

“Recognising that we are doing exceptionally well, having been diagnosed only 7 weeks ago.”

Discussion

Supporting parents of children diagnosed with diabetes is crucial in order to reduce parental distress, as well as to help children and young people manage their diabetes in the early stages of diagnosis and into their future.

The current group model provided a way of enabling parents to support each other, as well as obtaining support and advice from the Paediatric Diabetes team and parents whose children had lived with the condition for a longer time period. The group format also enabled families to meet with the Paediatric Psychology team early on in the treatment pathway. This is important given the importance of supporting families to “get off to a good start” (Watts et al, 2014) and the implications this has on early and later metabolic control (Wright, 2009). The group format also offered the families access to clinical psychology resources, which are relatively scarce at this critical time period.

The timing of the group (open to all families diagnosed in the previous 12 months) enabled families to access it at a time where they had already started to get to grips with the practical elements of diabetes care and had more space to consider the emotional impact (Waldron and Hall, 2020). The majority of families attending the group had children diagnosed for more than 3 months.

The late afternoon/early evening timing of the group (4 pm until 5:30 pm) may have also enabled more working parents to attend the group, which the authors feel would have been of great benefit (Clapton, 2017).

Suggestions for improvement

The parents attending the group welcomed the inclusion of a parent expert whose child had lived with the condition for a longer period of time. This supports the benefits of a Peer Support model (D’Urso and Ramful, 2020; Casdagli et al, 2019), but it is important that thought is given about how to remunerate children and parents who give up their time to support others.

Future workshops will aim to be delivered later in the evening to facilitate improved attendance and uptake of the group, particularly for working parents. The team has also considered running the group alongside parallel child/sibling sessions during school holidays, to promote attendance.

The questionnaire for the current study was developed by the authors based on the group’s aims. The lack of validation for this is considered a limitation of the current study, and further work is warranted to assess the validity of the questionnaire.

Finally, it could be argued that the online format enabled easier access to the group, particularly in a hospital Trust that spans across two sites and covers a large geographical area. There was some feedback, however, which suggested that some families would have found it helpful to meet with others in person. Previous in-person groups facilitated by the service incorporated a model of running parent groups alongside groups for children and siblings. Future plans include running one virtual and one in-person group annually, and giving families a choice of which to attend.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022