Patient safety is a key priority in any NHS Trust. People living with diabetes are particularly susceptible to harm due to potential medication errors and episodes of hypoglycaemia (NHS Digital, 2019). It is therefore essential that all Trusts have the right structures in place to make the hospital environment safe, particularly as one in six beds are occupied by someone with diabetes. In 2010, the National Inpatient Diabetes Audit (NaDIA) was launched to assess the quality of care for people with diabetes admitted to hospital. This annual audit, conducted over a week, highlights the huge variation in care across the UK. In 2018, the charity Diabetes UK launched its document Making hospitals safe for people with diabetes (Diabetes UK, 2018). A key recommendation from this document was the need for hospitals to have “knowledgeable healthcare professionals who understand diabetes”. This article describes an educational initiative to address this issue, implemented across adult inpatient areas in an NHS Trust in Leicestershire.

Background

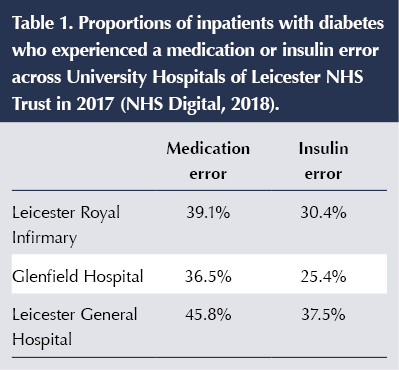

University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (UHL) is a large Acute Trust with more than 1100 beds spread over three sites. People with diabetes occupy 18.2–23.3% of beds. During 2014–2016, the inpatient diabetes team had implemented the national Think Glucose campaign (NHS England, 2011) across the Trust; however, this was aimed at educating nursing staff only, and the diabetes team struggled to provide ongoing regular education. Data from NaDIA in 2017 (NHS Digital, 2018) highlighted issues with both medication and insulin errors across all three sites (Table 1). The data highlighted an obvious gap in provision of education and training for all frontline staff across the Trust, and in November 2017 the Care Quality Commission (CQC) issued a warning notice to the Trust raising concerns around the safe use of insulin.

In 2017, insulin safety training was included as essential for all staff who prepared, prescribed or administered insulin. However, training was via an external e-learning package. Feedback from non-diabetes staff highlighted that training was difficult to access, was too detailed and contained content that was less relevant to the inpatient setting. Compliance with the training was poor and it was clear that training as a whole needed investigating, especially in light of the CQC warning notice.

It was agreed that all frontline, non-specialist staff who prescribed, prepared or administered insulin should be included in any educational strategy to drive the required improvements forward. The training needed to be accessible, relevant and focused on key safety messages. Delivery across all three sites had to be sustainable and outcomes needed to be monitored.

Developing an educational strategy

The inpatient diabetes team started work on an educational strategy that would achieve the following key objectives:

- Develop and deliver an effective inpatient diabetes educational toolkit which would be applicable or adaptable to meet the needs of doctors, nurses and pharmacists within the Trust.

- Ensure the strategy was deliverable and sustainable within the current workforce capacity of the inpatient diabetes team.

- Develop a consistent curriculum of key safety messages which could be delivered by other non-specialist healthcare professionals, such as the practice development nurse team.

- Increase compliance with insulin safety training.

- Create a supportive, positive reporting culture in which staff feel comfortable to identify and challenge poor care but also feel empowered to improve care in their areas.

- Monitor, evaluate and provide evidence on outcomes and user feedback.

The Inpatient team used information from the insulin safety task-and-finish group, which included non-specialist staff such as practice development nurses, to inform this work. The first step in achieving these objectives were to agree the key safety messages and topics that would be consistent across all the elements of training within the educational toolkit. Information from Datix reporting was used to prioritise topics and areas.

Key topics were identified as:

- Types of diabetes and who needs insulin.

- Common insulin errors (real-life scenarios).

- Safe use of insulin, including prescription, preparation and administration.

- Intravenous insulin (including perioperative in surgical areas).

- Capillary blood glucose targets/monitoring in inpatients with diabetes.

- Hyperglycaemia.

- Hypoglycaemia.

- Recognition of a “NaDIA Harm” (severe hypoglycaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis [DKA], hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state [HHS] or new foot ulcer).

- Prevention and treatment of diabetes emergencies and NaDIA Harms.

- Feet and feeds.

- Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and risk of DKA.

- Reflection on own practice, changing practice, championing good practice, challenging poor practice, and team working and communication to keep people with diabetes safe in hospital.

Key safety messages included:

- Insulin is a high-risk drug and can be fatal if incorrectly prescribed, prepared or administered.

- Be a safe prescriber of insulin. Remember the 6 Rs: Right person, Right insulin, Right dose, Right device, Right way and Right time.

- Never stop insulin in someone with type 1 diabetes (risk of DKA).

- Hypoglycaemia – treat promptly and prevent further hypos.

- Complete a Datix report for severe hypoglycaemia, in-hospital DKA/HHS or a new foot ulcer.

- Listen to the patient – they are usually the expert in their own care.

- Ask for help if you are unsure.

- Make diabetes management part of the clinical conversations at every board/ward round.

- Challenge poor quality of care.

The ITS Diabetes toolkit

Once this was done, the inpatient diabetes team went on to define and develop the key learning materials and supporting resources that would be included within the educational toolkit and would have an impact and audience both internally and nationally. The toolkit, named Inpatient Training and Support (ITS) Diabetes, consisted of the following:

- A PowerPoint slide deck for face-to-face training, which would be delivered to all frontline staff (including doctors, nurses and pharmacists) across all sites, delivered by consultant diabetologists, diabetes advanced nurse practitioners, inpatient DSNs and practice development nurses.

- An ITS Diabetes insulin safety e-learning module (created in-house; Box 1 and Figure 1).

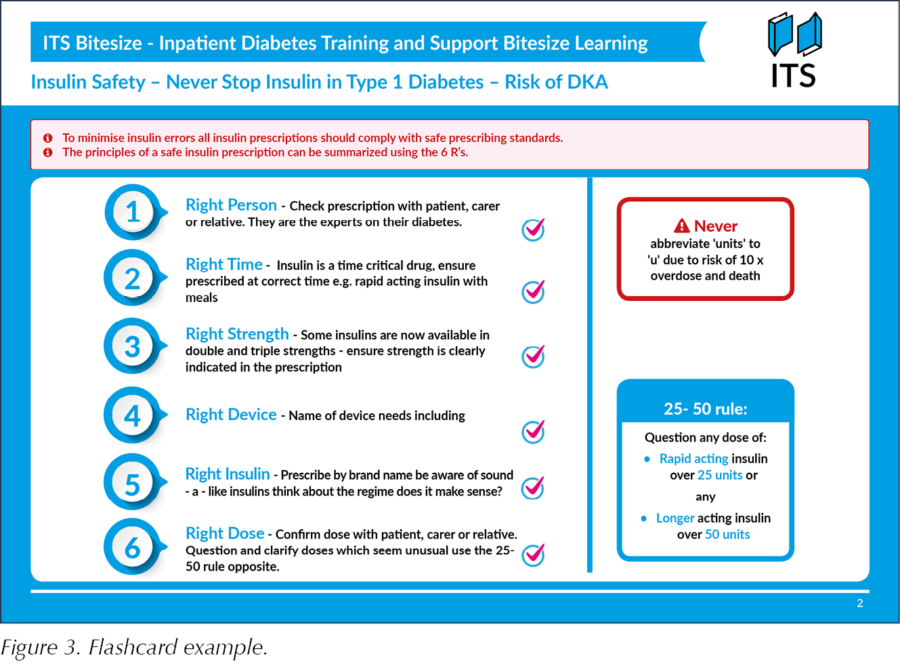

- A web-based ITS Diabetes handbook of inpatient diabetes care for junior doctors, externally hosted online via all platforms: PC, iPad, smartphone, laptop and so on (Box 2 and Figure 2).

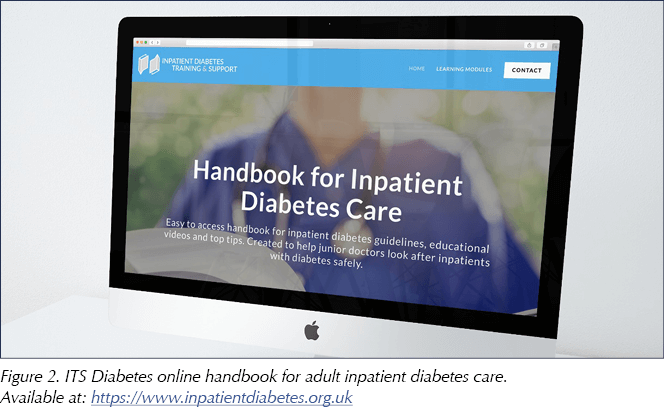

- A set of nine flashcards for “mini-teach” sessions (Figure 3).

- An ITS Diabetes key competencies document for junior doctors (self-assessment reflective practice).

- An ITS Diabetes newsletter.

- An ITS Twitter account (@ITS_diabetes_).

Following the development of the web-based handbook for doctors, other professional groups have expressed interest in using it. Since launch, its use has been promoted to all healthcare professionals, especially within the Twitter community, and is available at: www.inpatientdiabetes.org.uk. The handbook also contains short animated films to emphasise key messages. The variety of learning activities on this platform caters for all different types of learners (Barbe and Milone, 1981).

The flashcards are intended to be used for opportunistic teaching within the inpatient setting. It is envisaged that they would be given to specialist staff and used to address any issues they face when reviewing patients on the ward. Often the inpatient team have to speak to ward staff or doctors about treatment plans, so these flashcards serve as an ideal opportunity to upskill non-specialist staff. It is also hoped that these flashcards will be a resource to be kept on the wards, for example on notes trolleys, so that ward staff can refer to them when needed. Flashcards echo the key messages in the web-based handbook.

Quality assessment

At the start of this programme, the inpatient team agreed that it was important to measure outcomes to provide evidence of the effectiveness of the implemented educational strategy. These measures included hard outcomes from patient data as well as subjective feedback from staff. The following data were collected:

- A mini-NaDIA quarterly data collection in 13 data fields focusing on medication/insulin errors.

- In-hospital DKA episodes.

- Compliance with insulin safety training.

- Electronic incident reporting.

Results

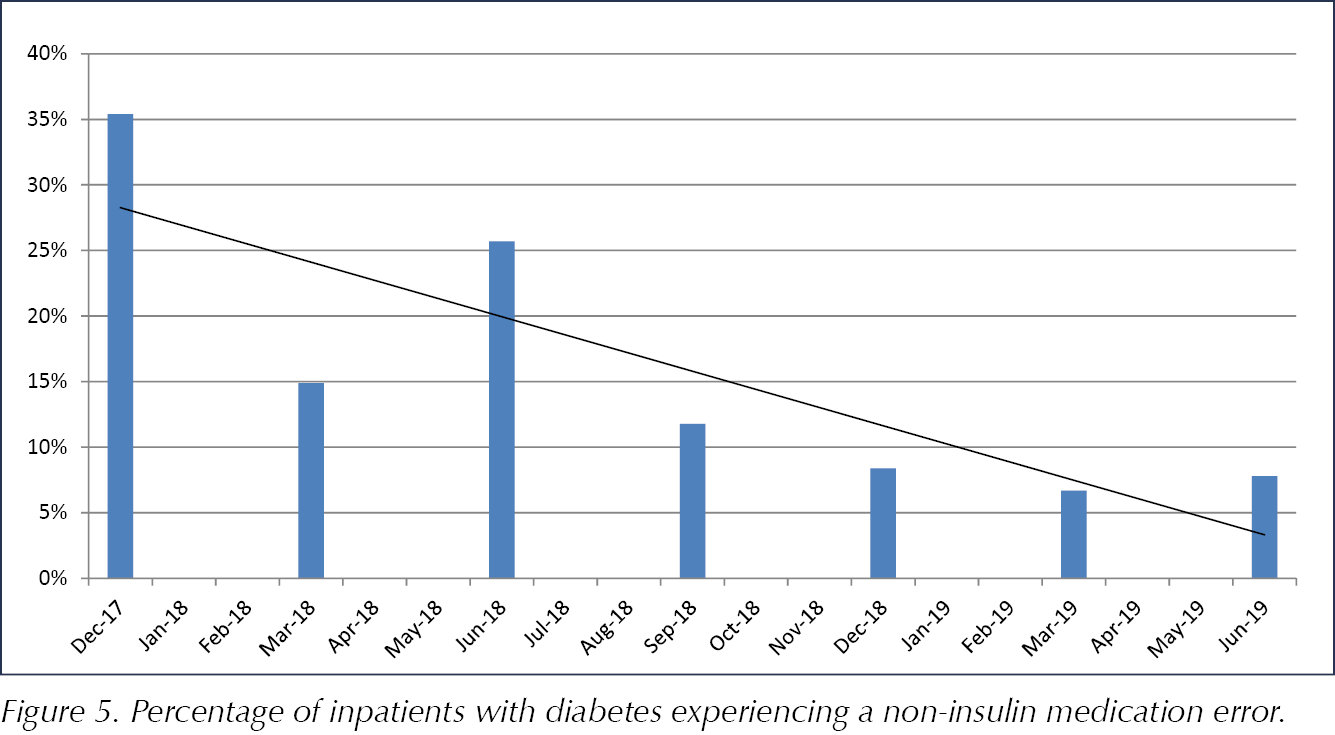

The introduction of the educational strategy aimed at training frontline staff and using a cohesive toolkit has resulted in significant improvements to inpatient care in UHL. From December 2017 to June 2019, the percentage of inpatients with diabetes experiencing an insulin error has reduced from 45.5% to 21.2% (Figure 4). Similarly, the percentage of people with diabetes experiencing a non-insulin medication error has reduced from 35.4% to 7.8% (Figure 5). There has also been a trend towards improvement of avoidable harm. Prior to the implementation of the educational strategy, the team were aware of anecdotal reports of approximately one DKA episode per month. Between September 2018 and November 2019, there has been a reduction in reported episodes of in-hospital DKA (four validated incidents of in-hospital DKA in 14 months).

Uptake of insulin safety training improved over the period of implementation, and feedback collected from 213 participants was positive. One of the participants said:

“Thanks for putting all of this together! I did the online module and I would say it’s actually really easy to follow and really good. I particularly like the videos and I think it is overall very useful.”

Uptake of the training has been increased by giving staff training options to suit different learning styles (Hawk and Shah, 2007) and different needs. The new in-house e-learning module was seen as easier to access and more relevant, and also allowed monitoring of completion/compliance. In April 2018, insulin safety training was included in the electronic training dashboard for all qualified medical, nursing, nursing associate, midwifery and pharmacy staff. Training for healthcare assistants was done specifically as face-to-face training. This training was essential-to-role and renewable annually. Staff were required to attend face-to-face training initially and then, at annual renewal, were permitted to complete training either by attending another face-to-face session or completing an e-learning module. At baseline (May 2018), the compliance rate for nursing staff was 56% and for medical staff 40%. This progressively improved, and in November 2019 these figures were 90% for nursing staff and 70% for medical staff. Engaging medical staff remains a challenge; however, automatic reminder emails to staff who are not compliant have been introduced, with a hope that this will improve figures further.

Data collected through electronic incident reporting supported the view that with training, support and empowerment, staff would become more confident in recognising poor-quality care and thus be more inclined to report incidents. As expected, reporting of incidents involving the keywords “diabetes” and “insulin” did increase following the introduction of the educational strategy; however, there was no increase in moderate or major harms reported (Table 2). This increase in reporting shows that staff were aware of safety issues and supports the view that an open, positive and supportive reporting culture facilitates improvements in patient care.

Challenges

The main challenge in implementing this educational strategy was staff time, both to develop and to deliver the training. Those who developed the content were given time to do this in their job plans. This was supported by the Trust’s senior executive team, who considered this education as a priority following concerns raised by the CQC. For delivery of the education, a “train the trainer”-type model was used to cascade training to staff across the Trust. Trainers were trained by the specialist team and used an approved slide deck for training sessions.

Finding time for staff to be released from frontline clinical areas was also a challenge; however, once again, the Trust supported this work as a priority. Time was saved because many staff chose to study via e-learning, which reduced the amount of face-to-face training time overall. Some staff preferred face-to-face training and they fed back that it was important to them because of the interactivity and the opportunity to ask questions. Although there is value in this form of training, its sustainability does rely on buy-in from wider teams within the Trust, such as the executive team and the practice development nursing team. It is hoped that the Trust will continue to support this kind of provision.

The e-learning elements of this strategy are more sustainable as they can be accessed flexibly by staff, with the only real cost being the time to develop the materials and time for regular review of content. Funding for the development and branding of the web-based junior doctors’ handbook was secured via a successful NHS England Transformation bid.

Lessons learnt

- When embarking on an initiative like this, it is essential to gain support from the senior executive team within the Trust, including medical and nursing leads. This can be done through auditing and presenting local data that highlight any harm occurring within the Trust.

- To ensure the sustainability of any new programme, it is essential to engage those who are going to help and support its delivery.

- Any successful inpatient diabetes education strategy must include doctors, nurses and pharmacists, as well as other frontline staff groups. A strategy that focuses on one particular professional group alone (e.g. nurses) will not tackle the issues adequately.

- Be open to training multidisciplinary groups. We found that there are real opportunities to improve communication and develop better team working across disciplines at multidisciplinary face-to-face training sessions.

- Agree key safety messages before you start in order to ensure consistency across any materials you develop.

- Ensure your strategy has many different elements to suit all different styles of learner (Hawk and Shah, 2007).

- See feedback from staff as a gift and be open to adapt the materials, as it is essential that staff feel the training is clinically relevant and that they have key messages/new knowledge to use in everyday clinical practice.

Concluding remarks

The key concepts of the ITS Diabetes toolkit are transferable across all Trusts in the NHS, which makes national rollout of such an initiative a possibility. The national profile of this strategy is already being raised through presentations at national and international meetings, and on social media via the ITS Diabetes Twitter account. With high-level buy-in from the executive team, the ITS Diabetes education strategy was successfully implemented in our NHS Trust. Implementation and sustainability to deliver this strategy was possible without compromising direct clinical contact time, and it has improved patient safety, making the Trust a safer place for people living with diabetes who are admitted to hospital.

Helping homeless adults to overcome the challenges of managing their condition.

16 Apr 2024