In the current NHS climate of driving sustainability and transformation plans and the challenges we face in the delivery of financial stability, there is good evidence that the NHS cannot be led by professional managers alone. It is essential that we involve clinicians in sharing leadership roles within an organisation (Ham et al, 2011). Effective clinical leadership is critical for securing sustainable improvements in the delivery of quality patient care. There is a case for change in the current NHS clinical leadership climate. If real change is to be embedded in any organisation and culture, it cannot be achieved by individuals alone; shared leadership is needed.

A new form of leadership

Responsibility for distributed leadership has to be spread across the system to include both diversity and compassionate leadership behaviours. New conceptions of leadership are needed within the NHS, and these will demand different leadership development approaches. Limsili and Ogunlana (2008) found that transformational leadership concepts can help facilitate organisational commitment and employee productivity. They also reported that employees led by transformational leaders have better health than those led by apathetic, hands-off leaders.

Clinical managers face challenges if they are to drive cultural change and provide effective leadership, such as dealing with workforce issues, conflicts and ensuring the delivery of high quality care, quality assurance and clinical governance without compromising patient care. They are also now responsible for managing financial matters and delivering cost-improvement programmes in light of growing pressures on the current NHS system and increased demands on services (The King’s Fund, 2010). The King’s Fund report on the future of leadership and management in the NHS states that ‘the NHS needs to recognise that the type of leadership the NHS requires is changing and the old model of heroic leadership by individuals needs to adapt to become one that understands other models such as shared leadership both within organisations and across organisations with which the NHS has to engage in order to deliver its goals’ (The King’s Fund, 2010). Organisations are required to focus on developing teams, not just individuals, towards better leadership across systems as a whole. Effective leadership in the NHS involves a system of collective leaders, not just one, who can actively embrace change. Leaders must enable widespread coalitions and collaboration. I believe that leaders and teams working together with a shared vision is essential in producing the productive outcomes desired.

Dynamic, effective and aware

The concepts of ‘situational leadership’ and ‘leadership that gets results’ are premised on similar principles of leadership styles (Hersey and Blanchard, 1969; Goleman, 2000):

- Self-awareness

- Being climate-dependent

- The ability to choose your style as a leader.

These leadership approaches offer a conceptual framework for dynamic leadership and each framework can be appropriately used in different settings. Effective leaders should learn to adjust their styles as their followers and situations change over time in a work environment (Hershey and Blanchard, 1969; Goleman, 2000). Leadership skills can be developed through five practices based on the framework proposed by Kouzes and Posner (2007):

- Model the way in which effective leaders work and set an example for your team members

- Inspire a shared vision within the organisation and share your aspirations

- Challenge the process if there are obstacles or difficulties to be faced; seek innovations that enable the process to grow and develop

- Enable others to act and allow others to be listened to; foster collaborations

- Encourage the heart by motivating team members; be positive as a leader and reward even small wins.

It is also important to recognise that the workforce consists of a wide variety of individuals with different skill sets, goals, interests and aptitudes. Kouzes and Posner (2007) state that ‘not everyone may want to learn it [the framework], and not all those who learn about leadership master it’. Leadership can be taught, but it can only be developed by those who have the drive, motivation and willingness to learn to be leaders (Kouzes and Posner, 2007).

Collaborative and motivational

Systems leadership concepts have been defined as ‘a collaborative leadership of a network of people in different places and at different levels in the system creating a shared endeavour and cooperating to make a significant change’ (Goss, 2015). Systems leadership is almost the opposite of a command-and-control approach. It is about creating a shared endeavour and vision by developing trustworthy and honest relationships because it is important that people believe in what they are doing.

Motivation is also an important factor to cultivate in teams within our everyday life and workplace environment. Motivation can be defined as the driving force behind all the actions of an individual (Brunstein, 2005). It affects our basic behaviours and has an impact on our inner drive to succeed over life’s challenges while we set goals for ourselves. Our motivation also promotes our feelings of competence and self-worth as we achieve our goals.

Integrity

A distributed leadership approach encourages openness to the boundaries of leadership, such that varieties of expertise are distributed across the many, not the few (Bolden, 2011). Leithwood and colleagues (2009) also suggest that certain forms of leadership approach, such as concordant alignment of team members, are more likely to contribute towards long-term productivity; misalignment and anarchic alignment will have a negative effect on organisational productivity. Deci and Ryan’s (2008) theory of self-determination suggests that people tend to be driven by a need to grow and gain fulfilment. The assumption of self-determination theory is such that people are actively directed toward growth, learning and development. This resonates with the importance of recognising and accepting that each individual will have their own set of motivators that predominate.

A personal leadership journey

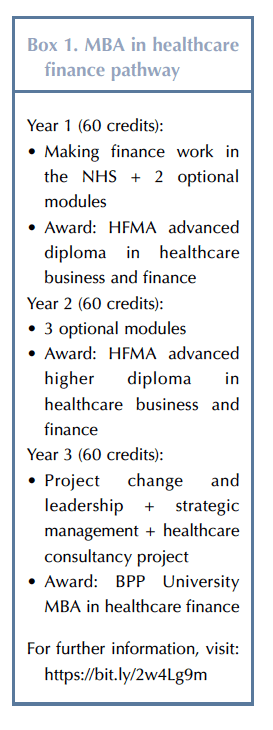

Everyone’s path towards leadership differs, depending on their skills, motivation, experience and NHS workplace. I graduated with an MBBS honours degree under full scholarship from the University of Sydney in, Australia. Following this, I went on to obtain a Masters in Medical Science (Diabetes and Endocrinology), a PhD in Child Heath and a Masters in Law. I was the first clinician in the UK to complete the HFMA Advanced Level 7 Higher Diploma in Healthcare Business and Finance, see Box 1 for details. I currently work as a clinical Consultant Paediatric Endocrinologist and an Associate Medical Director of an NHS acute trust. The role is demanding, varied and rather broadly defined. As a clinical manager, I have come to see leadership as a state of mind and a process of continuous learning. Leaders should not be complacent. To achieve personal effectiveness, I try and use my resources and develop my abilities to achieve my goals. Through my experiences, I continue to see that leadership skills are an ongoing process of learning, adaption and development that occurs within any organisation. Our willingness to learn is, I believe, fundamentally important in becoming a truly good leader.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022