Transition is the planned movement of young people with chronic illness between paediatric and adult healthcare settings (Blum et al, 1993). There is variability across diabetes settings in the UK in terms of how transition is planned for young people. Most UK services introduce the process to children from age 12, with the aim to transition by age 19 (Beskine and Owen, 2008; Colver and Longwell, 2013). Collaboration between paediatric and adult services is important in supporting young people with their transition (Flemming et al, 2002). Paediatric transition services need to be holistic and person-centred to be an effective process for the young person (Fernandes et al, 2014; Bridgett et al, 2015). Young people who have a good rapport with the medical team during their transition clinic appointment are more likely to feel empowered and motivated in managing their diabetes, therefore leading to improved outcomes (Rose et al, 2002; Babler and Strickland, 2016).

Our transition service consists of dedicated transition staff who attend all transition clinics. Staff members include two consultants (one paediatric and one adult), one paediatric registrar, one dietitian (paediatric), two transition specialist nurses (one paediatric and one adult) and one paediatric clinical psychologist specialising in diabetes. Clinics are run twice a month on Thursday afternoons. Although we start to introduce the concept of transition from age 13, young people do not attend the transition clinic until around their 16th birthday. They are then transferred to the adult service around their 19th birthday.

Many young people with type 1 diabetes experience a decline in glycaemic control, leaving them vulnerable during transition from paediatric to adult services (Allen and Gregory, 2009; Crowley et al, 2011; Rausch et al, 2012; Garvey et al, 2014; Sheehan et al, 2015). The literature suggests that difficult transition experiences can have a detrimental effect on diabetes management and overall health outcomes (Weissberg-Benchell et al, 2007; Peters et al, 2011). Some young people have reported dissatisfaction with their transition experience, leading to negative implications for their metabolic control (Pacaud et al, 2005; Busse et al, 2007; Garvey et al, 2012).

Guidelines produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) state the importance of involving young people in evaluating services in order to help them feel empowered and motivated in their diabetes care. It is therefore of the utmost importance to ensure that diabetes clinics are able to understand the needs of young people going through transition between paediatric and adult care (Diabetes UK, 2017). There is, however, a dearth of research to reflect what young people in transition experience throughout this journey (Forbes et al, 2001; Gray et al, 2018). Furthermore, Campbell and Waldron (2017) remind teams that service development should be informed by feedback from young people on their transition experience. To date, our diabetes transition service has relied on self-report questionnaire feedback from young people. This study hopes to add to the evidence base on how best to support young people living with diabetes throughout their transition years by examining the views of those attending our diabetes transition clinic using a focus group.

Method

Study design

A focus group was conducted in June 2016 at our diabetes transition clinic. The aim of the group was to gain an understanding of young people’s experiences of the transition clinic, to learn from them about what they need to have a good experience, and to consider possible service improvements. A qualitative design was used to capture a range of lived experiences, perceptions and feelings among the young people (Morgan, 1996; Krueger and Casey, 2014). The focus group was registered as a service evaluation project and was approved by the safety quality and support team within the hospital. All participants and their parent(s)/guardian(s) gave written informed consent. All participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

The focus group was facilitated by one clinical psychologist and two transition nurse specialists. The questions were developed by the facilitators in line with current literature on transition needs for young people with diabetes (Garvey et al, 2014). The facilitators worked together to ensure that all young people had the opportunity to voice their opinions.

Participants

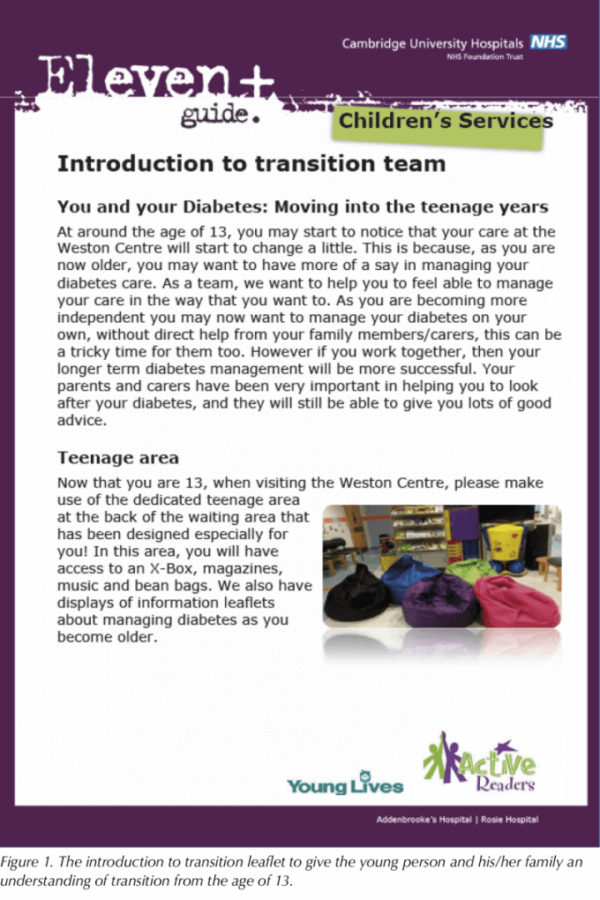

All of the young people (n=80) who attended the diabetes transition clinic were invited by mail to attend the focus group. Of these, five attended, see Table 1. The mean age of the group was 17 years. All of the young people who attended our focus group were actively going through transition at the time of the group and as such were not attending adult services at that point in time.

Data analysis

The clinical psychologist audio recorded the group discussion and transcribed the notes verbatim. The transcriptions were read a number of times to develop themes from the data. Participants’ responses to the open-ended questions were transcribed and analysed by one researcher (SA). The transcription was also independently analysed by a second researcher (JA) to ensure consistency. The two researchers met on a regular basis to analyse the data in line with thematic analyses (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Each researcher coded the data by categorising key words and emerging themes. The researchers applied this framework to the transcript until theoretical saturation was agreed upon. The researchers then met to discuss the final themes.

Findings

Four core themes emerged from thematic analysis:

- Fear of transition to a new clinic after having spent all of their diabetes care in a paediatric setting

- Transition feeling like a change and movement of care

- Difficult experiences of the transition service

- Ideas for an improved transition service experience.

Fear of transition to a new clinic

The young people shared many common views about their anxiety of transitioning to the adult diabetes clinic. Some members of the group felt that having been in the same setting for all of their diabetes care over several years made the process of moving to an adult clinic “scary” or more daunting:

“It is scary to be going somewhere else after being here for so long. I have spent the last 7 years getting to know this team and now I have to go to a new team where they won’t know me as well.”

“It’s scary; there are lots of new faces.”

A change and movement of care

The prospect of transition brought up themes of change and movement for the participants:

“It feels like going from one place to another, like a new environment with new people and getting to know new people again.”

“It’s like moving to a new city or a new house; it’s like a different environment.”

Difficult experiences of the transition service

Further themes emerged relating to difficult experiences of transition care. Some described feelings of being “patronised” by the team, including clinic staff, during transition appointments:

“The man calls his thing that takes your blood his little wand […] it makes me feel like I’m being really patronised and it makes me not want to be here.”

“[I want to be] spoken to like my age, like not treating me like I’m 5.”

Interaction with doctors was a consistent theme:

“It makes me not want to talk to the doctors when I feel patronised. I get really rude and like, I just don’t speak. I just shrug my shoulders at anything that’s said to me.”

“I don’t like it when doctors make that listening noise. It sounds like they are pretending to listen, but they don’t really pay attention.”

“They are on the computer and not making eye contact; it just feels like I am talking to myself.”

“The doctor not being too personal but being interested.”

Participants reflected on the different feelings about their behaviours they had experienced during clinic appointments:

“Sometimes I forget to put stuff in my pump and I feel like I am going to be told off.”

“It’s hard. People have said if I don’t do my insulin I can die and that’s really hard to hear.”

“The whole appointment was about something that I wasn’t doing well, and I literally came out and cried because it made me feel that what I was doing wasn’t good enough […] It’s not just me, but my mum tries really hard and my whole family tries really hard just to make sure that my diabetes is fully under control, and you go in there and [are] told that what you’re doing isn’t good enough and I just feel that why am I even bothering?”

Ideas for an improved experience

Participants shared ideas as to how they believed their needs could be better met:

“Helping us to figure out what we are doing wrong and suggesting solutions.”

“Setting targets would help.”

“Little steps help it to feel more like an accomplishment when you reach that target.”

“Sometimes letters from the doctors about what we talked about doesn’t come through for weeks after the appointment and we forget. Having something simple written down about what was discussed, the targets and the name of the doctor with a contact number would be really helpful.”

“It is helpful to see the same doctors and team members each time.”

“Going to see the environment [young adult diabetes clinic] would help.”

Participants consistently felt that praise was needed to empower them during their appointments:

“You could say something that could be improved, and then follow it up with a few things that you actually are doing well…”

“It would be nice to get some praise because I am trying really hard.”

“It would give me more motivation to want to keep going so I don’t give up.”

The inclusion of family members in transition appointments, particularly parents, was important:

“I think my parents should get more respect in my appointments. I came in once and it was all about me and they weren’t asking any questions to my parents. I just found it quite rude. My diabetes doesn’t just affect me; it affects my mum too.”

The majority of participants described the importance of having time on their own during a clinic appointment, as well as time with their parent or guardian:

“Some of the appointment you should have whoever comes with you in with you, and then they can go and speak to another nurse or someone else if they have any questions and then you just carry on speaking to that doctor.”

“Having time so the doctors can ask questions with my parent there and then time to ask me questions without them there…”

Peer support groups were something the participants felt were valuable:

“It’s a relief to meet other young people who know what it’s like to go through it.”

“The Tree of Life group that I did in February was really helpful. It […] was really helpful and nice to meet other diabetic children.”

Discussion

This study explored the experiences and views of young people living with diabetes who attend our transition service. It hoped to empower them to have a voice, in terms of what they feel needs to be improved. Thematic analysis demonstrated a shared lived experience among the young people. This included anxieties regarding transition to adult services and difficulties experienced during transition clinic appointments, as well as ideas for future service improvements. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have found similar themes among young people attending diabetes transition services (Allen and Gregory, 2009; Crowley et al, 2011; Garvey et al, 2014; Sheehan et al, 2015; Gray et al, 2018).

Feelings of dissatisfaction with the transition service were identified through the thematic analysis. This is consistent with other studies (Pacaud et al, 2005; Busse et al, 2007; Garvey et al, 2012). Such studies have noted the detrimental impact this may have upon diabetes management.

Our findings appear to show that a difficult appointment leads to feelings of discouragement in terms of diabetes management. The young people reported that feelings of being patronised led to resistance to engage in their consultation. Young people did not want to be “told off” during their consultation; they suggested clinicians help them to find solutions and to set targets to manage their diabetes. However, this would need to be realistic, as they requested “little steps to feel more accomplished”.

Young people felt that an increase in praise during clinic appointments could lead to an increase in motivation to improve their diabetes management. They felt that a good appointment would consist of staff being friendly, interested and not too personal. They stressed it was important for the clinician to make eye contact, rather than to focus on the computer. Findings indicate that the young people valued their consultation ending on a positive note. This is consistent with other studies, suggesting that young people need to feel empowered by their medical teams during the period of transition in order to improve overall diabetes management (Rose et al, 2002; Babler and Strickland, 2016). Further research is needed to explore this concept as this may help transition clinics learn more about what is needed to help young people feel motivated and empowered to manage their diabetes.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2016) guidelines advise asking the young person how he or she would like his or her parents/carer to be involved, and this should be asked on a regular basis. This includes when the young person has moved to adult services. The young people in the current study felt they would still like their families involved in their appointment, however they also felt they needed some time and space to discuss things with the clinician on their own. Research could further explore family involvement during transition and the impact this may have on the young person’s clinic experience and glycaemic control.

It is important to note that the current study is reflective of a small sample of young people living with type 1 diabetes. Four of the participants were pump users. It is often thought that pump users are more motivated to manage their diabetes, and this could be a reason these participants attended our focus group despite all young people in transition being invited. All of the young people were white and from middle class families. The findings could therefore be biased. However, the key themes that emerged from the data were consistent across participants.

Application in practice

The findings from our focus group highlighted that young people would like a summary of the outcome of their clinic appointment in addition to their GP letter. As a team, we have taken this feedback on board and are in the process of developing a Diabetes Clinic Appointment Summary Template that will be used by the transition team. This will include the name of the doctor the young person saw, their last HbA1c and their HbA1c at the time of the clinic appointment. The form will also include a summary of the goals that were set during the young person’s appointment. The team is aware that praise should be included within this summary and we will ensure the template captures this.

Two leaflets have been devised for young people and their families. One is to give the young person and his/her family an understanding of the concept of transition from the age of 13, see Figure 1. The other leaflet is given when the young person attends their first transition clinic appointment to help him or her and their family to learn more about how the clinic works.

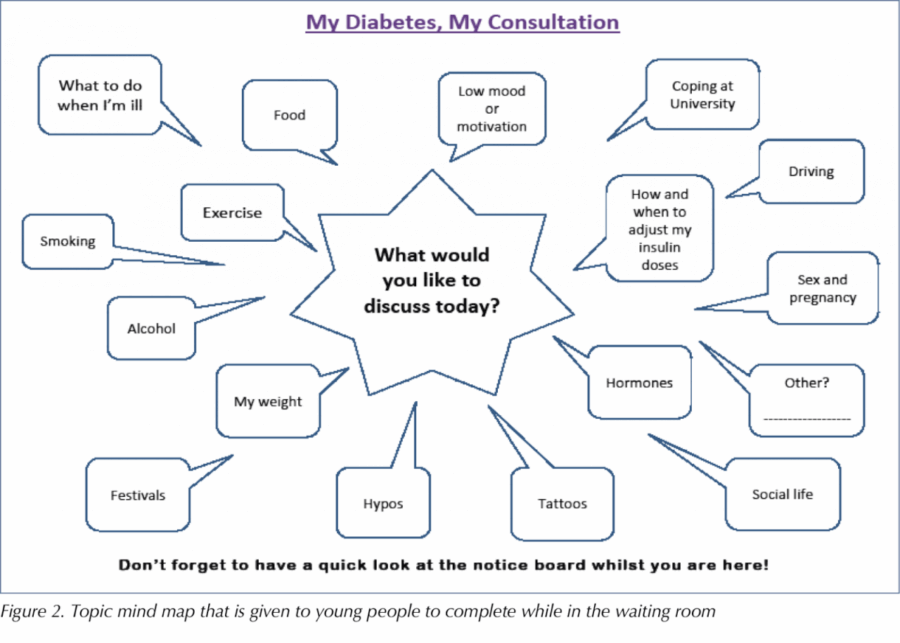

We have a ‘Topic Mind Map’ for the young person to complete while they are in the waiting room, see Figure 2. This aims to help to empower the young person in preparing for the consultation. For example, information about how they can manage their diabetes during festivals, preparing for university and alcohol use, etc.

In addition to this, on a yearly basis we give out a diabetes network questionnaire on the young person’s transition journey. The aim of this is to obtain qualitative data as a whole network so we can identify how to improve our transition services.

Conclusion

The findings from this study may help guide the development of diabetes transition clinics. Locally, the findings have led to all young people in transition having the opportunity to look around the young adult diabetes clinic as part of their transition to adult services. The medical team has reported that the findings have influenced their practice in terms of being more mindful of how they communicate with young people and their families during consultations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants and the peer reviewers for feedback on the manuscript.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022