The incidence of type 2 diabetes in younger individuals is increasing (Misra et al, 2023), resulting in more women of childbearing age living with this condition. Non-optimised glycaemic control preceding a pregnancy increases risk to both mother and baby, including risks of stillbirth, congenital abnormalities and perinatal mortality.

To reduce the risk of unplanned pregnancy and these serious outcomes and complications, effective preconceptual counselling and contraception are crucial for all women of childbearing age living with diabetes (Schwarz et al, 2012; Robinson et al, 2016; ADA Professional Practice Committee, 2025). Unfortunately, studies indicate a substantial gap in knowledge among women with diabetes regarding the increased risks associated with diabetes during pregnancy, as well as low rates of effective contraception in this group (Cartwright et al, 2009; Robinson et al, 2016).

General practice is a common site where women attend for contraceptive services, making us well placed to assist women with this important issue.

The impact of hormonal contraceptive therapies on diabetes

The Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH, 2019) states that the use of hormonal contraceptives, including combined oral contraceptives, has a limited impact on daily insulin requirements and does not influence long-term glycaemic control or the progression of retinopathy. For a woman with diabetes without other cardiovascular risk factors, microvascular complications, obesity or a history of cardiovascular disease, there are few limits on choice of contraception.

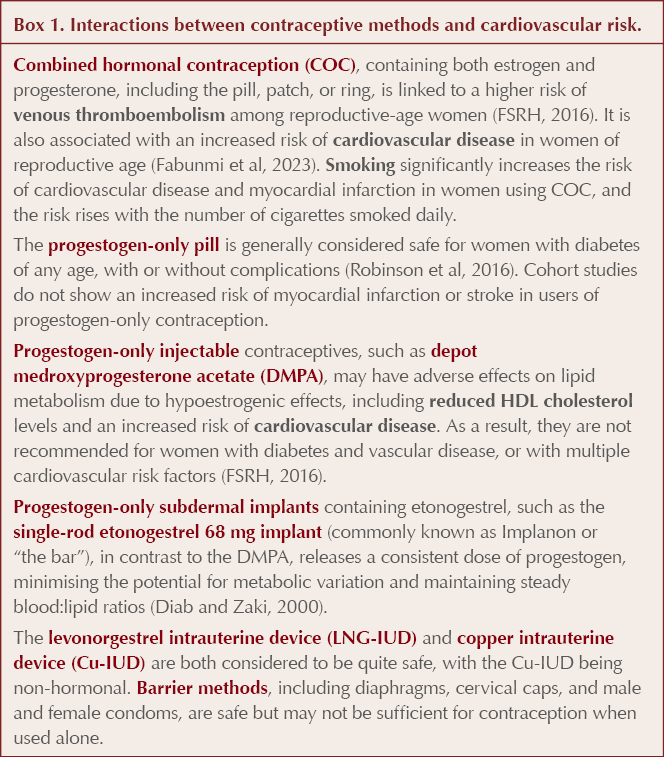

However, individuals living with diabetes, and particularly those with early-onset type 2 diabetes, often have one of the above issues alongside their diabetes. Various contraceptive methods have different effects on these comorbidities (Box 1), making the situation more complex.

Using the UKMEC to help with contraceptive choices in women with type 2 diabetes

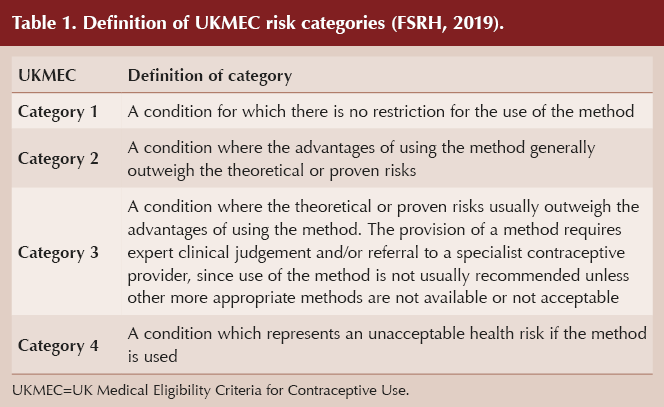

The UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (UKMEC) offer guidance on the safety of various contraceptive methods for different patient groups but do not indicate the “best” method or their effectiveness (FSRH, 2019). They provide valuable information when considering contraception in women with diabetes. They rank conditions into four categories of risk (Table 1).

Traditionally, we may have understood that the UKMEC criteria were additive, but the FSRH explicitly states that this is not the case; thus, having two conditions in UKMEC category 2 does not necessarily add up to a UKMEC category 4 for a particular contraception form. Instead, if multiple UKMEC 2 conditions are present that relate to the same risk, we are encouraged to use our clinical judgement and advise the individual that her risks may outweigh her benefits with that form of contraception. This is particularly relevant when considering diabetes.

Diabetes and UKMEC recommendations (FSRH, 2019)

Women with a history of gestational diabetes

Women with a history of gestational diabetes who return to normal blood glucose levels after pregnancy can use any form of contraception.

Women with diabetes, without complications or multiple cardiovascular risk factors

For women with type 2 diabetes without complications, the copper intrauterine device (IUD) has no usage restrictions (UKMEC 1).

Other contraceptives, including combined oral contraception (COC), the progestogen-only pill, the depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) injection (Depo-Provera), the single-rod etonogestrel 68 mg implant (Implanon) and the levonorgestrel IUD, fall under UKMEC 2, meaning their benefits generally outweigh any risks. These guidelines apply to all women with type 2 diabetes, whether or not they use insulin.

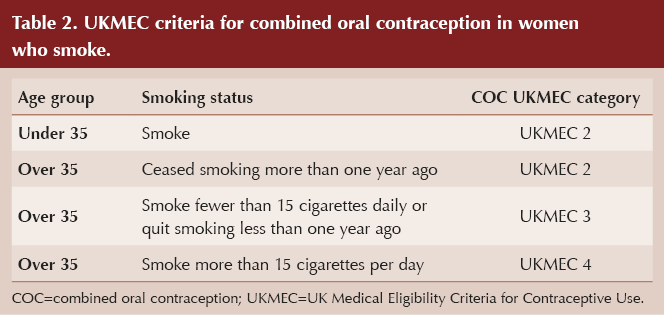

Smoking history

Copper and levonogestrel IUDs, the progestogen-only pill, etonogestrel implant and the DMPA injection are safe (UKMEC 1) in women who smoke, regardless of age.

COC has different UKMEC classifications according to age and smoking history and amount (Table 2). The age of 35 years is used as the cut-off because excess mortality from smoking becomes apparent at this point (Vessey et al, 2003).

Women living with overweight or obesity, with or without diabetes

Obesity is a common risk factor for the future development of type 2 diabetes, and many people with type 2 diabetes also have obesity. Thus, contraception is of prime importance in women of childbearing age living with obesity.

Copper and levonogestrel IUDs, the progestogen-only pill, the etonogestrel implant and the DMPA injection are considered safe (UKMEC 1) in women who are living with overweight or obesity, regardless of age or whether the woman has a history of bariatric surgery. Notably, the levonorgestrel IUD is associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer in women with overweight or obesity who have a higher baseline risk of this condition (Wan and Holland, 2011; Derbyshire et al, 2021).

COC is designated UKMEC 2 where a woman has a BMI of 30–34 kg/m2, but this rises to UKMEC 3 when BMI is ≥35 kg/m2.

Bariatric surgical procedures involving a malabsorptive component have the potential to decrease oral contraception effectiveness, and this may be further decreased by postoperative complications such as long-term diarrhoea and/or vomiting.

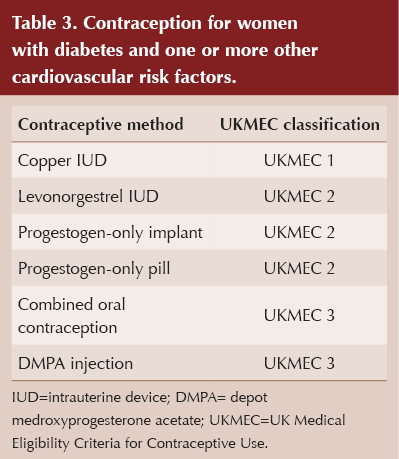

Women with diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors

When multiple significant risk factors (two or more, including diabetes) are present, the likelihood of cardiovascular disease increases considerably. For women without established cardiovascular disease who have diabetes and one or more other cardiovascular risk factors (including smoking, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidaemia), UKMEC classifications are listed in Table 3.

Women with vascular disease, with or without diabetes

According to the UKMEC criteria, vascular disease encompasses coronary heart disease with angina, peripheral vascular disease with intermittent claudication, hypertensive retinopathy and transient ischaemic attack.

The use of COC in this group is classified as UKMEC 4, indicating an unacceptable risk. The DMPA is classified as UKMEC 3 due to concerns regarding hypoestrogenic effects and reduced HDL-cholesterol levels. The effects of DMPA may persist for some time after discontinuation.

The progestogen-only pill, etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel IUD are generally classified as UKMEC 2 for this group. However, if a woman develops new ischaemic heart disease or has a stroke while using any of these three methods, the classification changes to UKMEC 3. The duration of use of progestogen-only contraception in relation to the onset of disease should be carefully considered when deciding whether continuation of the method is appropriate. Cohort studies do not show an increased risk of myocardial infarction or stroke in users of progestogen-only contraception.

While there is a theoretical concern about the effect of levonorgestrel on lipids, the FSRH recommends that the levonorgestrel IUD may be continued in cases of developing ischaemic heart disease, with clinical judgment and assessment of pregnancy risk and other factors being necessary. This is rather confusing given the UKMEC 3 criteria mentioned above. No clarification is given as to what the cut-off point is between new and chronic ischaemic heart disease.

The copper IUD is considered safe (UKMEC 1) for women living with diabetes and vascular disease.

Women with diabetes and microvascular complications

For women with type 2 diabetes and microvascular complications (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy), the copper IUD is classified as UKMEC 1.

Progesterone-containing contraceptives (progestogen-only pill, DMPA, etonogestrel implant and levonorgestrel IUD) are classified as UKMEC 2.

However, COC falls under UKMEC 3, indicating that the risks generally outweigh the benefits or require expert clinical judgment.

Newer diabetes therapies and contraception

Use of injectable incretin therapies for type 2 diabetes and weight management, such as GLP-1 and GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists, is increasing, including among women of childbearing age. Currently, there is a lack of safety data on the use of incretin-based drugs during pregnancy.

The FSRH has issued a statement summarising the contraceptive implications of these medications. Patients should be advised to use contraception while using all incretins and related medications, and be informed about the recommended washout periods between stopping the medication and planning a pregnancy (FSRH, 2025). These vary between the various medications in this class.

Exenatide is recommended to have a washout period of 3 months, and semaglutide 2 months. Tirzepatide has a recommended washout period of 1 month.

Drug interactions between incretin therapies and oral contraceptives

In pharmacokinetic studies, no clinically relevant reduction in the bioavailability of oral contraceptives has been observed with semaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, dulaglutide or lixisenatide (FSRH, 2025). Tirzepatide was the sole medication in the group to exhibit a clinically significant impact on the bioavailability of oral contraceptives.

Women using tirzepatide in combination with oral contraceptives are advised to transition to a non-oral contraceptive method or incorporate an additional barrier method for 4 weeks after starting tirzepatide and for 4 weeks following any dose increase.

There is no recommendation to add a barrier method of contraception when using oral contraceptives with semaglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, lixisenatide or liraglutide.

However, there is an additional consideration when translating these data and recommendations into clinical practice. The potential for gastrointestinal side effects must be considered.

Contraceptive implications of gastrointestinal side effects in women taking incretin therapies

The Summaries of Product Characteristics for all GLP-1-based therapies state that diarrhoea and vomiting are either very common (≥10% of users) or common (≥1% of users) side effects, particularly during dose escalation periods. These effects may impact the absorption of oral contraceptives, potentially reducing their efficacy.

Individuals experiencing severe diarrhoea or vomiting whilst using GLP-1 agonists and oral contraception should adhere to the following recommendations (FSRH, 2025):

Follow the missed pill guidelines in the manufacturers’ instructions if vomiting occurs within a few hours of pill intake or if severe diarrhoea persists for more than 24 hours.

Consider non-oral contraception methods for individuals with persistent vomiting or diarrhoea.

Consistent use of condoms is recommended in these situations.

Conclusions

Contraception is an important service which primary care is well placed to provide, and is of particularly great importance in women who have type 2 diabetes, both to avoid fetal and maternal complications due to high blood glucose and to avoid any teratogenic effects of diabetes medications. However, diabetes and its associated comorbidities and risk factors bring additional complexities to contraception choice. This highlights the depth of the value and service which patients receive from the holistic approach of their general practice teams.

Risk of CVD and cardiovascular mortality differ between people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, and between men and women.

2 Oct 2025