What are ARBs?

Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) operate on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and, like ACE inhibitors (ACE-Is), are used in the treatment of hypertension, heart failure and chronic kidney disease, notably in the case of diabetic nephropathy. They can also be prescribed for prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with a previous myocardial infarction or at high risk of a cardiovascular event.

ARBs have similar efficacy to ACE-Is across a range of indications but carry the advantage of reduced side-effects, with a lower incidence of drug-induced cough and angioedema. Thus, they are frequently chosen when ACE-Is cannot be tolerated.

ARBs are non-peptide molecules with clear similarity in molecular structure (indicating a class effect).

Mechanisms of action1

Effects on blood pressure

● Inhibition of the action of angiotensin II (a potent vasoconstrictor) facilitates vasodilation and lowers blood pressure (BP).

- Unlike ACE-Is, ARBs do not increase bradykinin levels, circumventing the bradykinin-induced cough and angioedema that can arise with use of ACE-Is.

● Inhibition of angiotensin II activity results in decreased aldosterone levels, reducing sodium and, hence, water retention in the kidneys (natriuresis), leading to reduced blood volume, thus lowering BP. ARBs may also counter direct sodium and water retention by angiotensin II itself.

Effects on heart failure

● The vasodilatory effects of ARBs reduce afterload, enabling increased cardiac output in heart failure.

● Myocyte hypertrophy is reduced, protecting against left ventricular dysfunction.

● Following myocardial infarction, the renin–angiotensin system is activated, and this can lead to left ventricular dilation and impaired function. ARBs counter these effects.

● ARBs also act centrally on the autonomic nervous system, inhibiting sympathetic activity, which protects against arrhythmias and the development of heart failure.

Renal effects

● Vasodilation of the glomerular efferent arterioles reduces intraglomerular pressure and preserves the glomerular basement membrane; thus, ARBs have a renoprotective effect.

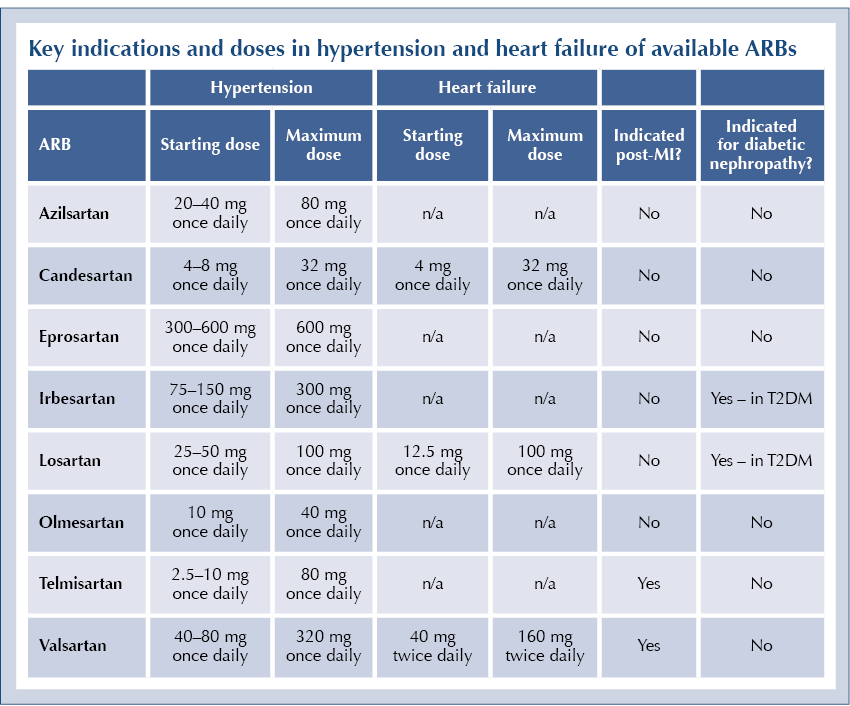

Licensed indications

The licensed indications for ARBs vary between class members but include:

● Hypertension: alone or in conjunction with other anti-hypertensives.

● Heart failure or asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

● Post-myocardial infarction: secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and heart failure.

● Prevention of cardiovascular events in people with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or type 2 diabetes with organ damage.

● Diabetic nephropathy.

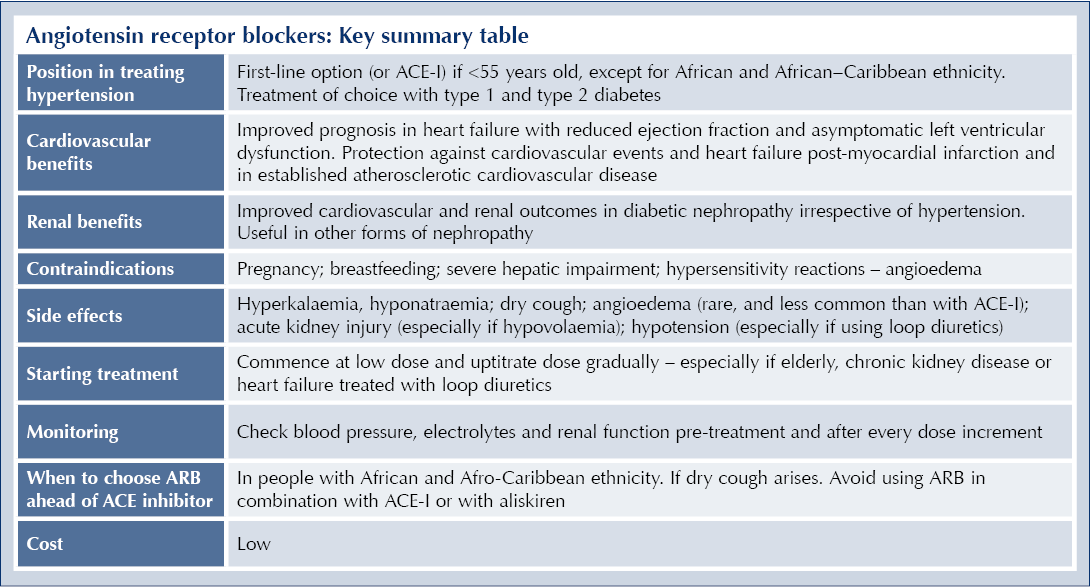

Positioning in guidelines

Hypertension

● NICE NG136 recommends ARBs (or ACE-Is) as first-line antihypertensives in people <55 years old.2

- For those >55 years old and those with African or African–Caribbean ethnicity, calcium channel blockers (CCBs) should be offered as first-line antihypertensive agents, with thiazide-like diuretics an alternative if CCBs are not tolerated or contraindicated.

● ARBs (or ACE-Is) are first-line treatment for hypertension for all adults with type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes because of their cardiorenal protective properties.2,3

● ADA guidelines recommend ARBs (or ACE-Is) as first-line antihypertensives for people with diabetes or established coronary artery disease.4

● ARBs are a second-line option for a person whose hypertension is not controlled with a CCB (or thiazide-like diuretic) and can also be added to a combination of a CCB and thiazide-like diuretic as part of triple therapy.2

● If an ACE-I is poorly tolerated (e.g. because of cough), an ARB can be offered.2

● For people with African or African–Caribbean ethnicity, an ARB should be chosen ahead of an ACE-I.2

Heart failure (NICE NG106)5

● For people intolerant of ACE-Is, ARBs should be offered as an alternative first-line treatment to individuals with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (alongside a beta-blocker).

● Valsartan in combination with the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril is recommended as an option for symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV symptoms) heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (35% or less) in people previously established on either an ARB or ACE-I.

Chronic kidney disease (NICE NG203)6

Whether or not hypertension is present, ARBs have an important role in treating chronic kidney disease (CKD), notably when albuminuria is present, to slow the progression of renal disease and reduce cardiovascular risk.

● For people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, offer an ARB licensed for diabetic nephropathy (or an ACE-I), titrated to the highest licensed dose tolerated, if urinary albumin:creatinine ratio (uACR) is 3 mg/mmol or more.

● For people without diabetes, offer an ARB (or ACE-I) titrated to the highest licensed dose tolerated if uACR is ≥70 mg/mmol. If hypertension is also present, offer if uACR is >30 mg/mmol.

● ADA guidelines recommend an ARB (or ACE-I) for people with diabetes who have albuminuria to prevent the progression of renal disease.4

Acute coronary syndromes and stable angina (NICE NG185)7

If people are intolerant of an ACE-I, an ARB may be offered, titrated up and continued indefinitely:

● Post-myocardial infarction for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (alongside dual anti-platelet therapy, beta-blockers and statins).

● If there is established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (e.g. previous myocardial infarction, stable angina).8

Principal effects

● ARBs are effective in reducing BP and preventing end-organ damage, including cardiovascular events, either as monotherapy or in combination with other antihypertensive agents.9

- ARBs have the advantage of better tolerability than ACE-Is, with reduced incidence of cough and angioedema.

● In people with diabetes and hypertension (without other complications), ARBs have similar cardiorenal outcomes as other antihypertensive agents.10

- In individuals with hypertension, diabetes and signs of left ventricular hypertrophy, losartan was found to be superior to the beta-blocker atenolol in reducing the primary composite outcome of stroke, myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death.11

● ARBs reduce all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for heart failure in individuals with symptomatic congestive heart failure with reduced ejection fraction compared with placebo.12

- Comparison studies with ACE-Is indicate that ARBs provide equivalent outcomes for people with heart failure.13

● ARBs are an effective alternative to ACE-Is in reducing mortality post-myocardial infarction in those with left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure.14,15

● Irbesartan was found to reduce the progression of microalbuminuria and facilitate reversion to normoalbuminuria compared with placebo in people with type 2 diabetes and hypertension.16

- Irbesartan and losartan have demonstrated reductions in decline in renal function and incidence of end-stage renal disease in people with established diabetic nephropathy.17,18

- In all of these studies with ARBs, benefits were accrued independently of BP-lowering effects.

- Renoprotection from ARBs extends to normotensive people with diabetes and proteinuria, notably if uACR is >30 mg/mmol.19 ARBs also attenuate decline in eGFR and proteinuria in people with non-diabetic chronic kidney disease.20

● ARBs have equivalent benefits to ACE-Is. In people with diabetes, ARBs are as effective as ACE-Is both in renoprotection and cardiovascular protection (cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, angina pectoris, hospitalisation for heart failure).21

- In populations not limited to having diabetes, ARBs appear to provide similar benefits to ACE-Is in lowering BP and improving total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes and in reducing proteinuria.22,23

Contraindications

● Pregnancy and where pregnancy is planned: teratogenic effects, including reduced fetal renal function and oligohydramnios.

● Breastfeeding: limited information.

● Hypersensitivity reactions.

● Bilateral renal artery stenosis: risk of acute kidney injury (AKI).

● Severe hepatic impairment.

Cautions

● Aortic or mitral valve stenosis: risk of severe hypotension.

● History of angioedema.

● Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

● Hypovolaemia: ARB can reduce renal function and predispose to AKI and hyperkalaemia under these circumstances.

● High-dose diuretic therapy (e.g. >80 mg furosemide).

● Low systolic blood pressure (<100 mmHg): risk of hypotension.

● Reduce dose in moderate hepatic impairment.

Drug interactions

● Avoid using ARBs and ACE-Is in combination – outcomes are not improved and there is increased risk of hyperkalaemia and AKI.24,25

● ARBs should not be used in combination with aliskiren (a direct renin inhibitor) in people with diabetes.

Adverse effects

● The incidence of dry cough with ARBs is significantly less than with ACE-Is because bradykinin levels are not raised. If a cough arises with an ACE-I, an ARB can be offered.

● Hyperkalaemia: secondary to reduced levels of aldosterone.

- Higher risk if other potassium-retaining medications are being used, such as potassium-retaining diuretics (e.g. amiloride) and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (e.g. spironolactone).26

- More likely if initial eGFR is <45 mL/min/1.73 m2, or if initial potassium level is >4.5 mmol/L.

● Hyponatraemia: secondary to reduced levels of aldosterone.

● Angioedema: rare, but potentially life-threatening swelling of face, lips and upper airway.

- ARBs have a 2–3-fold lower risk than ACE-Is.27

- Increased risk of angioedema in people of African and African–Caribbean origin, so choose ARB in preference to ACE-I in this ethnic group.2

- If angioedema experienced with ACE-I then avoid ARB.2

● Acute kidney injury: higher risk if pre-existing CKD or renal artery stenosis; can be precipitated by hypovolaemia.

● Hypotension: higher risk of first-dose hypotension in individuals with heart failure and low systolic blood pressure taking high dose of loop diuretics (e.g. furosemide).

- Start with a very low dose of ARB under these circumstances.

Prescribing tips5,6,26

Initiation

● Have available baseline electrolytes and renal function before starting ARBs.

● Start ARBs at a low dose and titrate up at short intervals (e.g. every 2 weeks), until the maximum tolerated or target dose is achieved.

● Use lower starting doses and titrate up more slowly in older people or those with CKD (notably if eGFR is <45 mL/min/1.73 m2).

● Avoid starting ARBs if baseline potassium is >5 mmol/L. If necessary, consider altering any potassium-retaining medication (e.g. amiloride, spironolactone) to allow use of ARBs.

Monitoring

● Monitor blood pressure before and after each dose increment of ARB.

● Measure serum electrolytes and renal function 1–2 weeks after starting an ARB and after each dose increment.

Potassium

● If serum potassium is 5.0 mmol/L or more after starting an ARB, look for other causes of hyperkalaemia. If possible, stop or reduce the dose of potassium-sparing diuretics, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists or nephrotoxic drugs (e.g. NSAIDs).

● A potassium level of up to 5.4 mmol/L is acceptable. If 5.5–6.0 mmol/L despite taking measures to reduce levels, reduce dose of (or if necessary, stop) ARB to achieve potassium levels that are acceptable.

● If potassium rises to >6 mmol/L and other potassium-retaining medications have been discontinued where possible, stop ARB and refer immediately to hospital.

eGFR

● A cumulative fall in eGFR of <25% or a rise in serum creatinine of <30% from baseline are acceptable. If these are exceeded, look for other possible causes, including hypovolaemia or concurrent medication (e.g. NSAIDs) before stopping or reducing the dose of ARB.

Sick day rules

● Temporarily withdraw ARB if hypovolaemia (e.g. diarrhoea and vomiting) to reduce risk of AKI and hyperkalaemia – increased risk of AKI if taking loop diuretics.

Key summary table

Poster abstract submissions are invited for the 21st National Conference of the PCDO Society, which will be held on 19 and 20 November.

10 Apr 2025