Poor attendance at young adult clinics presents a major barrier to this population accessing the support and care that they need (Hynes et al, 2015), therefore increasing risk of serious and long-term implications for their physical and emotional wellbeing. This, in turn, places demands on the healthcare system to treat medical complications secondary to poorly managed diabetes in later life (NHS England, 2016). Furthermore, anxiety and depression in young people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) have been associated with difficulties in non-concordance with treatment (NICE, 2016) and consequently an increased cost to health services through ward admissions and incidents of diabetic ketoacidosis (NHS Wales, 2017).

National guidance for diabetes services has highlighted the need for a significant redesign of the transition process with a focus on putting the service user experience at the centre (NHS England, 2016; NHS Digital, 2017; NHS Wales, 2017; Diabetes UK, 2018). This study sought to capture the experiences and opinions of these young people to inform this process.

Background

Emerging adulthood, as defined by Arnett (2000), is a critical period of development that has implications for a young person’s wellbeing, quality of life and health outcomes (Hanna, 2012). Developmentally, 18–24-year-old people have different levels of cognitive and social emotional maturity, and services need to adapt to their needs cost-effectively and provide better long-term outcomes for the individual. Dovey-Pearce and Christie (2013) highlight the neurobiological implications of poorly managed diabetes and emphasise the need to support emerging adults to “develop the skills and strengths required to meet self-care challenges.”

Studies highlight the benefits of services working flexibly and creatively to remove barriers to accessing services, in addition to enabling young people to connect with peers (Ng et al, 2017); particularly as attendance at clinics has been shown to deteriorate following transition to adult services (Sheehan et al, 2015). Furthermore, acknowledgement of diabetes distress and opportunities to talk about this with healthcare professionals and peers has also been found to be important to young adults living with T1D (Balfe et al, 2013).

Specific interventions that aim to improve outcomes for young adults living with T1D are reported widely. Systematic reviews of the literature conclude, however, that the quality and design of interventions require further development to effectively meet the needs of this population (Wafa and Nakhla, 2015; O’Hara et al, 2017; Schultz and Smaldone, 2017).

The literature highlights the importance of understanding the perspectives of this population (Hanna, 2012) and seeks to understand the key factors involved in successful transitional care (Findley et al, 2015; Schultz and Smaldone, 2017). Research emphasises the need for diabetes transition services that are co-designed with due consideration of emerging adults’ individual developmental experiences (Hilliard et al, 2014) and the changes in their relationships with peers, parents and professionals during this process (Bridgett et al, 2015).

Qualitative research has previously proved effective for engaging with young people in conversations about their experiences of living with T1D. These have focused on engagement with clinic appointments (Snow and Fulop, 2012) and the process of healthcare transition (Garvey et al, 2014). Results highlight the influential role of collaborative relationships between service users and providers (Ritholz et al, 2014; Hynes et al, 2015), and the need for support during early adolescence to develop the necessary skills for diabetes self-management into adulthood (Babler and Strickland, 2015). Rasmussen et al (2011) discuss how young adults employ different strategies to navigate the challenges they face at this stage of life, and identify these in relation to two transition processes; diabetes transitions and life development transitions.

Aim

The aim of this study was to gain service user insight into how services for emerging adults living with T1D can be commissioned and developed to meet the specific needs of this population. This includes addressing their health style behaviours and supporting them with possible psychosocial barriers.

Method

Design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by a clinical psychologist between February and August, 2019. The interviewing psychologist was part of the diabetes multidisciplinary team but was not known to the participants. Qualitative research with this population has previously proved effective for engaging young people in conversations about their experiences of living with T1D. The design was selected as an appropriate method for capturing and exploring the lived experiences of this population. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the interviews were audio recorded.

Participants

Six participants (one female; five males) with a diagnosis of T1D were recruited through their routine contact with their adult diabetes team across two hospital sites. Recruitment was open to those aged 18–24 years, with the final recruited participants’ age range being 20 years 6 months to 23 years 7 months old.

Data analysis

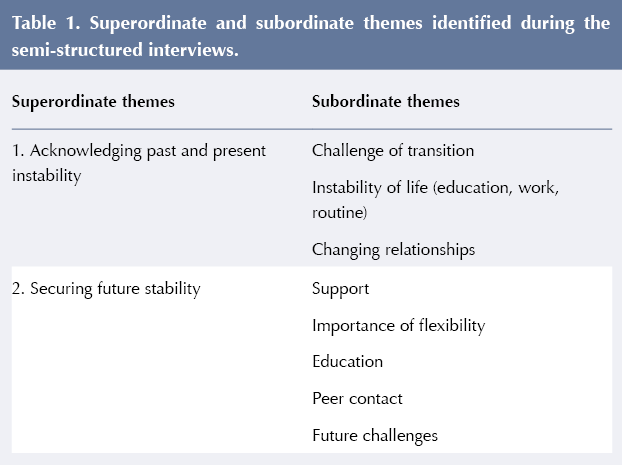

The interview audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA). The guiding principles of IPA (Smith et al, 2009) present the most sensitive method for handling the personal thoughts, opinions and experiences that are shared by participants. The analysis process results in the development of superordinate and subordinate themes. Transcriptions and themes were also independently analysed and verified by the second researcher.

Results

Two superordinate and eight subordinate themes emerged from the data analysis (see Table 1).

Acknowledging past and present instability

Challenge of transition

There was huge variability in the reported experiences of the process of transitioning from paediatric to adult services. While some participants could recollect attending a transition clinic before the move to adult services, others had been transferred with no joint handover. Consistency across experiences highlighted a lack of clarity about the process, its timings and expectations at each stage.

“The way the transition was presented to me by (my paediatric diabetes nurse) wasn’t how it turned out to be” (Participant 3).

“I sort of assumed it would be like less, you get less support almost from it [adult service]… …the government, because they reckon all people that are a month older than what they were last time don’t need that same support anymore” (Participant 1).

Participants reflected on the impact of the particular challenges of this stage of their lives, including educational and employment pressures, their own changing attitudes and priorities, as well as the ongoing process of adjustment to living with a diagnosis of T1D.

“….even now I am still struggling adjusting to the thought of having diabetes” (Participant 3).

Some suggested a post-transition process of follow-up from their paediatric key worker could have helped bridge the gap between services.

“…the people that know you are sort of looking after you a little bit – just sort of pushing you into that direction, even just a phone call or just to make sure you have gone [to the adult clinic] and you are still doing OK…” (Participant 2).

Instability of life (education, work, routine)

Participants highlighted the concurrent timing of transitioning between services and key life transition stages, and the challenges this has presented. The requirement to adapt to multiple changes during this period and adjust to the unpredictability of the adult world can lead to a realignment of priorities for young adults, with diabetes management being pushed further down the list.

Participants reported experiencing little acknowledgement of this in the design and delivery of diabetes services. There was also a sense of the psychological impact of living with diabetes during this time not being recognised due to more of a focus on practical matters by clinicians.

“…it’s not their fault, but to have a team that doesn’t, like, live with the condition, cos [sic] for them they are, like, their title is diabetic doctor or diabetic nurse, so for them it’s like diabetes should be the centre of your life, but it’s, like, actually there are things that I am worried and concerned about that sometimes have to take priority…” (Participant 3).

“…there is a lot more psychological issues that I think I have personally faced in regards to, like, dealing with diabetes that would have helped my management better than that actual management being an issue…” (Participant 3).

Changing relationships

In life, relationships are constantly evolving, and this is no less true for emerging adults. There was a notable shift of emotional and social dependence from parents to peers, with a struggle to find a balance between achieving sought-after independence while still relying on parental support for finances and practical issues (for example, arranging appointments and picking up prescriptions). There was also apprehension around navigating conversations about T1D with peers, partners and colleagues.

“…on the first time that you are, like, properly going out with them you wouldn’t want to be like, ‘oh yeah, I’ve got this wrong with me’ would you?….. [what if] they don’t want to be with you because of it and they can’t be bothered with it…” (Participant 4).

Being understood and held in mind by professionals was identified as an important factor in facilitating engagement with diabetes teams during challenging periods.

Securing future stability

Support

Considering improving self-management of diabetes, a common theme was the development of a positive and open relationship with diabetes team members in order to access appropriate, timely support. They identified accessibility, consistency, confidence in diabetes professionals’ up-to-date technological knowledge and approachability as key factors. A known point of contact for queries was also valued by participants, alongside easy access to a full multidisciplinary team including dietitians and psychologists.

“…it’s more personal and they come across as though they do actually care for you as a person and not ‘ah well your blood sugars have been fine so off you go’….obviously you are not just diabetes, you are the person…” (Participant 6).

“…[the doctor] is focusing on the bio part but like, it’s OK, but there is also the social and psychological and you’re not taking that into consideration, so I think having [psychologists] in the clinics would help because….it would have helped like giving a more holistic treatment rather than just be like ‘OK, what’s the biological problem’…” (Participant 3)

Importance of flexibility

Given the demands of emerging adulthood, flexibility in accessing diabetes services was a priority for participants, so that their diabetes did not impact their daily lives more than necessary. A range of appointment times and the use of technology (such as email, text, Skype, phone calls) for flexible contact were suggested.

“…I found very useful was phone call conversations with [diabetes nurse]….two minute conversation, it doesn’t take up an appointment space, you’re not sat around here [clinic] for two hours for a ten-minute appointment…” (Participant 4).

The idea of a “one-stop shop” clinic where patients have access to all members of the multidisciplinary team, if required, for checks, support, advice and education was repeatedly raised. This was with a view to ensuring clinic appointments were worthwhile and to promote convenience and efficiency.

“…it’s a question of work and stuff because you never know where you are going to be with my job…..I’m not saying it’s a nuisance to get your check-ups done because you have to go, it’s just something else to do whereas if it’s all in one it’s just easier…” (Participant 5).

“…if you are going to see everybody and you’re going to get everything done that you should get done, so long as people know about it you can plan round it…” (Participant 2).

Education

Participants desired access to further diabetes education in various formats. Suggestions included basic awareness training for family, peers and partners, regular but brief updates via clinic appointments or email, and group educational sessions on key diabetes topics.

“…I’m not a book person whatsoever, so there are a lot of times throughout the time of being diabetic where you just kind of [get given] books… if I am honest because I don’t read them because it’s not informative for me because I learn by, like, people showing and doing” (Participant 4).

A broader curriculum of topics from the multidisciplinary team was requested, covering issues such as diabetes burnout, diabulimia, preparing for university, diabetes technology and the effects of diabetes on drug use and sex. Participants shared that while they had some awareness of these issues, they were limited in the extent of their knowledge and confidence in managing them.

“…more of the practical side of it, what might this [drugs/sex] do to your blood sugars, what might this do to your body” (Participant 1).

Peer contact

Participants expressed a desire to take up opportunities to meet, in person, with peers in the T1D community, rather than rely on social media platforms. While reluctant to initiate such contact themselves, they envisaged diabetes teams having a role in facilitating these opportunities through coordinating education groups, peer mentorship programmes and shared clinic spaces. There was recognition of the power of shared understanding and experiences between peers that is not available elsewhere, despite the empathic efforts of others, and the effects of different language use.

“…speaking to someone with diabetes is a lot better, like obviously they [professionals] have done all the work but, like, living with diabetes is completely different to out of the text book, it’s just not the same…” (Participant 6).

“…the terminology that I use is very different to what the professional is gonna use…” (Participant 1).

“if there is something that they do and they [peers] have found helps them then you could pick up things like that…” (Participant 5).

Future challenges

While acknowledging the current challenges of emerging adulthood, participants also voiced their awareness of future challenges and pressures they are yet to face. Issues relating to finances, housing, family planning, relationships and their diabetes prognosis were all raised.

“…my biggest concern is giving diabetes to my kids…” (Participant 2).

“…when you are living in your own place you have got to do everything yourself…” (Participant 5).

These reflect the lifelong implications of living with the condition and highlight the continuous role of services to offer support to individuals. Although participants identified family support as being important for dealing with these challenges, there is a particular responsibility on diabetes services to attend to the acute and anticipated emotional burden of the condition through appropriate and timely means.

“…It [diabetes] literally impacts everything and I think that is what bores me because I do go through stages where I’ve just had enough and I don’t take care of it and then it’s a continual cycle basically. You can’t win…” (Participant 6).

“…one-to-one talking is fairly beneficial…even talking now has been beneficial to me…” (Participant 2).

Discussion

The findings from this study are consistent with previous research and identify the following implications for practice and key recommendations for the development of young adult diabetes services:

● Transition between services should be planned with the young person’s direct input, with clear expectations of the process from all parties involved that acknowledge the individual’s circumstances and developmental needs. This assessment of readiness should include factors relating to the key developmental tasks of young adulthood, as part of identity exploration, which could affect diabetes self-management; education, living situation and employment (Monaghan et al, 2015; Saylor et al, 2019).

● Services should offer programmes that explicitly prepare emerging adults for independent diabetes self-management (including appointment booking, ordering and collecting prescriptions, accessing additional advice). Preparing young adults sufficiently with the necessary skills and knowledge prior to their transition to adult services is likely to contribute to better outcomes post-transition (Garvey et al, 2017).

● Each patient should have a consistent, named key worker or point of contact to allow them to feel personally known and understood by the team and facilitate engagement and openness. Sensitivity to the emotional, developmental and behavioural factors that influence the patient–provider relationship has been shown to be significant in supporting positive post-transition experiences (Ritholz et al, 2014).

● Clinic appointments should be person-centred, with clinicians trained in communication skills for this age group. There is increasing understanding of the neurological changes that take place in the emerging adult’s brain, which requires clinicians to adapt their communication style, helping the patient to feel secure and considered (Colver and Longwell, 2013). Emerging adults have a desire for developmentally appropriate interactions with their diabetes care providers (Hilliard et al, 2014), and a person-centred approach may help to address some of the difficulties previously experienced by patients in adult diabetes services (Iverson et al, 2019).

● Support from a knowledgeable multidisciplinary team for a range of current and anticipated issues should be made available at clinic appointments to promote convenience, efficiency and timely intervention for the patient. Relationships have been demonstrated between stressful life events during young adulthood and concurrent difficulties in diabetes self-management and glycaemic control (Joiner et al, 2018). This further highlights the need for appropriately qualified professionals embedded within diabetes teams equipped to offer psychosocial support in managing such life stressors and their impact on the individual’s diabetes care. Identifying and attending to the psychological needs of this population could be supported through the routine use of psychological screening questionnaires (Quinn et al, 2016).

● Technology should be used routinely to facilitate easy and accessible contact with the team, and the distribution of diabetes updates and education. With the continuing advancement of diabetes technology, diabetes clinicians are encouraged to consider innovative ways of delivering diabetes care, such as telemedicine or shared medical appointments (Raymond, 2017).

● A broad curriculum of education in a variety of accessible formats should be provided.

● Opportunities for regular peer contact should be facilitated by diabetes teams through education groups, peer mentorship programmes and age-banded clinics. Support groups facilitated by multidisciplinary teams could positively affect the emotional wellbeing and self-care behaviours of young adults (Markowitz and Laffel, 2012).

Limitations

The generalisability of this study is limited by the small sample size. It is believed, however, that the qualitative methodology allows a greater depth of understanding of the participants’ lived experiences. There may also have been a sampling bias due to only recruiting from a population that was attending an adult clinic and therefore does not capture the experiences of those who have disengaged from services completely. Furthermore, the participant sample had a male majority and may therefore be limited in the extent to which it provides insight into the unique experiences of young women living with T1D.

Conclusion

Research over recent years has drawn attention to the importance of facilitating a successful transition between paediatric and adult services for young people living with T1D. This study has explored the experiences of emerging adults post-transition, and identified their ideas regarding how young adult services can be developed. Services should support the engagement of these young adults with their diabetes teams, and promote improved physical and emotional health behaviours during this challenging period.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the study’s participants who generously gave up their time to contribute to the research and so honestly shared their experiences.

The authors would also like to express their thanks to Dave Ashbey, Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Knowledge, Library and Information Service.

NHSEI National Clinical Lead for Diabetes in Children and Young People, Fulya Mehta, outlines the areas of focus for improving paediatric diabetes care.

16 Nov 2022